the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Polyphase tectonic, thermal and burial history of the Vocontian basin revealed by U–Pb calcite dating

Louise Boschetti

Malou Pelletier

Frédéric Mouthereau

Stéphane Schwartz

Yann Rolland

Guilhem Hoareau

Thierry Dumont

Dorian Bienveignant

Abdeltif Lahfid

The Vocontian Basin in southeastern France records a long-lived history of subsidence and polyphase deformation at the junction of Alpine and Pyrenean orogenic systems. This study aims to reconstruct the tectonic, burial and thermal evolution of this basin, based on new U–Pb dating of calcite from veins and faults combined with new RSCM (Raman Spectroscopy of Carbonaceous Material) thermometry and stratigraphy-based burial models. Three main generations of calcite are identified: (1) the Late Cretaceous to Paleocene period related to the Pyrenean-Provençal convergence (∼ 84–50 Ma); (2) the Oligocene period linked to the extension of the West European Rift (∼ 30–24 Ma); and (3) the Miocene period, ascribed to strike-slip and compression associated with the Alpine collision (∼ 12–7 Ma). No older ages related to the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous rifting phase are obtained, despite targeted sampling near normal faults, suggesting highly localized syn-rift fluid circulation or dissolution of early calcite mineralization during subsequent tectonic events. RSCM data highlight a pronounced east–west thermal gradient. Peak temperatures are below 100 °C in the west and exceed 250 °C in the eastern basin, reflecting greater crustal thinning and salt diapirism in the eastern Vocontian Basin with the overlapping Jurassic and Cretaceous rifting phases. These results emphasize the significant impact of the West European Rift in south-eastern France. They further highlight the potential mismatch between large-scale tectonic processes and the tectonic history inferred from calcite U–Pb dating, which is sensitive to the presence of fluids and the physical conditions required for their preservation.

- Article

(15244 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1000 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

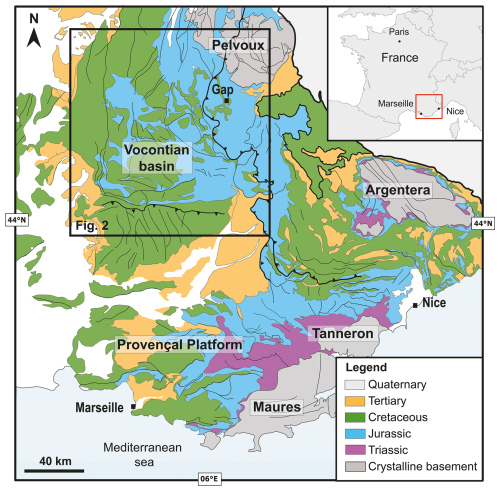

Sedimentary basins in the external part of orogenic belts offer critical insights into the polyphase evolution of plate boundaries. The Vocontian Basin is located at the front of the southern Alpine belt in southeastern France (Figs. 1, 2A). This region recorded a succession of tectonic events from the Mesozoic to the Cenozoic (Roure et al., 1992; Homberg et al., 2013; Mouthereau et al., 2021). They are attributed to Mesozoic rifting in the Alpine Tethys and the Atlantic-Pyrenean systems, Cenozoic inversion during the Pyrenean-Provençal collision, and Eocene-Miocene extension associated with the West European Rift and the opening of the Gulf of Lion (e.g., Homberg et al., 2013; Bestani et al., 2016; Espurt et al., 2019; Célini et al., 2023). Details of the tectonic evolution of the Vocontian Basin specifically, at the intersection between the Europe-Iberia and Europe-Adria plate boundaries, are however debated. There has been a long-standing debate on whether the Mid-Cretaceous Vocontian Basin is part of a continuous rift linking the Valaisan Basin and the Alpine Tethys to the Pyrenean Basin and Atlantic Ocean (Trümpy, 1988; Stämpfli and Borel, 2002; Turco et al., 2012), or if it belongs to the broader segmented Pyrenean/Atlantic rift system (Debelmas, 2001; Manatschal and Müntener, 2009; Angrand and Mouthereau, 2021; Célini et al., 2023; Boschetti et al., 2025a, b). Despite structural and sedimentary evidence of mid-Cretaceous syn-depositional normal faulting in the basin (e.g., Homberg et al., 2013), brittle deformation lacks precise geochronological data. Establishing this chronology is critical, as the Cretaceous extension often overlaps with the onset of Pyrenean compression (Fig. 2B) and could also be linked to diapirism (Bilau et al., 2023b). It is also unclear whether this part of the Alpine foreland was tectonically affected by the Eo-Oligocene West European Rift extension seen nearby in Valence and Manosque basins (e.g., Ford and Lickorish, 2004), or with the opening of the West Mediterranean well identified in the thermal record of the Maures-Esterel massif, a few tens of kilometers to the south (Fig. 2B) (Boschetti et al., 2023, 2025a, b). These Cenozoic thinning events may have impacted the thermal evolution of the Vocontian Basin and be confused with Mid-Cretaceous extension or Alpine thickening (Fig. 2B) (e.g., Célini et al., 2023). In addition, two north-south compressional events dated to Eocene and late Miocene are recognized in the fault pattern of Provence (Bergerat, 1987; Lacombe and Jolivet, 2005). The role of all these major tectonic phases in the brittle deformation history and in the related thermal regime remains unclear as recent studies in the basin have not yet successfully isolated the effects of each geodynamic event. In particular, the temperatures reconstructed based on Raman Spectroscopy of Carbonaceous Material (RSCM) support two alternative tectonic scenarios. (i) Temperatures from the Digne Nappe reflect crustal thickening below the propagating Alpine nappe stack (Balansa et al., 2023). Alternatively, a model involving two superimposed phases of crustal thinning in the Vocontian basin has been proposed (Célini et al., 2023; Fig. 2B). The first phase, in the Upper Jurassic, coincides with the Alpine Tethys opening, while the second, characterised by temperatures exceeding 300 °C in the Lower Cretaceous, is associated with Pyrenean rifting and Valaisan opening (Célini et al., 2023). Basin-scale geochronological and thermal analyses are needed to validate this tectonic intepretations. This study addresses these questions by combining basin-scale U–Pb dating of calcite in faults and veins, which origins are constrained by paleostress inversions, with new RSCM temperatures and the analysis of the burial history of the Vocontian Basin. Our aim is to establish a robust chronological framework for the Vocontian basin in the context of the geodynamics of south-east France, and to clarify the sequence and extent of the successive tectonic phases. These constraints improve our understanding of polyphase deformation at the Europe-Iberia-Adria plate boundary.

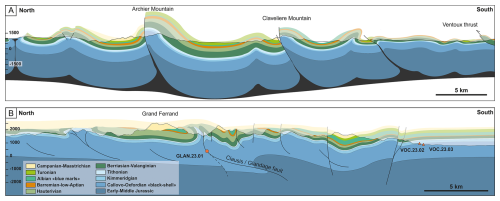

Positioned at the front of the Western Alps, the Vocontian Basin forms part of the Southern Subalpine belt, which developed through the interactions between the Pyrenean-Provençal belt to the south and the Alpine belt to the east (Philippe et al., 1998; Balansa et al., 2022; Célini et al., 2024; Fig. 1). It includes the Diois-Baronnies region, and is bordered by the Rhône Valley and the French Massif Central basement to the west, the External Crystalline Massif of Pelvoux to the east, the Vercors Massif to the north, and the Provençal Platform to the south (Figs. 1, 2A). The Vocontian Basin contains a thick Mesozoic sedimentary succession, reaching up to 7000 m in its center and 2600 m along its margins (Fig. 2B). The base of the folded stratigraphic sequence comprises Upper Triassic evaporites, which have resulted in the formation of salt diapirs (e.g. Suzette and Propiac diapirs) that pierce the overlying sedimentary cover and locally control thickness variations (Fig. 3A) (Célini, 2020 and references therein).

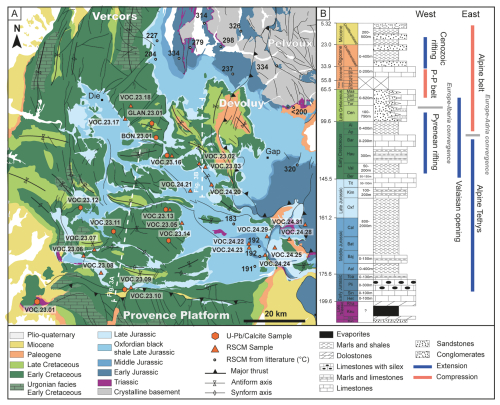

Figure 2(A) Geological map of Vocontian Basin with sample location and RSCM temperatures (°C) after Bellanger et al. (2015) and Célini et al. (2023). (B) General stratigraphic section of the Vocontian Basin and main tectonic events in the region.

Basin subsidence began with the opening of the Alpine Tethys during the Early to Middle Jurassic (e. g. Lemoine et al., 1986). This period is marked by the deposition of alternating shallow marine limestones and marls, followed by progressive deepening that culminated with the deposition of organic-rich black shales of the “Terres Noires” formation during the Bathonian–Oxfordian (Fig. 2). In the Late Jurassic, the basin underwent NNE–SSW-directed extension, recorded by syn-sedimentary NNW–SSE-trending normal faults (Homberg et al., 2013). This extensional regime, linked to the propagation of the Alpine Tethys, led to the deposition of fine-grained bioclastic Tithonian limestones, which serves as a distinctive morphostructural marker and reflect slower subsidence (Joseph et al., 1988). The subsidence continued through the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian-Aptian), with the deposition of alternating layers of marls and limestones that define the deeper marine “Vocontian facies”, contrasting with shallow-water carbonates of the Vercors and Provence platforms, known as the “Urgonian facies” (Fig. 2A).

A major tectonic shift occurred during the Aptian–Albian, characterised by increased subsidence and the deposition of thick marly sequences (“Blue Marls”; Debrand-Passard et al., 1984) (Fig. 2B). This phase is associated with the development of E–W-trending normal faults, suggesting a reorientation of the extensional stress field from NNE–SSW (Late Jurassic) to WNW–ESE (Homberg et al., 2013). This shift likely reflects plate tectonic reorganization, linked to the onset of Europe–Iberia divergence (Bay of Biscay opening) and the closure of the Alpine Tethys through Europe-Adria convergence (Lemoine et al., 1987).

During the Late Cretaceous, sandstones deposition dominated in the east of the basin, while limestones prevailed in the west (Fig. 2). In the north-eastern part of the basin, at the current location of the Dévoluy massif, a stratigraphic hiatus spanning the Turonian, Coniacian to the Santonian (Fig. 3B) is documented, regionally referred to as the Turonian unconformity (e. g. Flandrin, 1966). This interval is characterized by the argillaceous to sublithographic lower Cretaceous limestones and E–W-trending folds, which lie in direct contact, below an erosional surface, with Campanian-Maastrichtian bioclastic and terrigenous deposits (Figs. 2–3B; Gidon et al., 1970; Arnaud et al., 1978). Across the Vocontian basin, the main stratigraphic hiatus corresponds to the Paleocene-Early Eocene (Fig. 2B). This late Cretaceous-Paleocene event coincides with the onset of Iberia-Europe convergence, marking the initial stages of the Pyrenean-Provençal orogeny (∼ 84 Ma; Angrand and Mouthereau, 2021; Mouthereau et al., 2014; Muñoz, 1992; Teixell et al., 2018; Ford et al., 2022) and is consistent with the exhumation of the Pelvoux crystalline basement to the northeast at ∼ 85 Ma (Fig. 2; Boschetti et al., 2025a).

Figure 3North-South geological cross-section of the Vocontian Basin (A) and the Dévoluy massif (B). Location is presented in Fig. 2. Note that Coniacian and Santonian are missing (see explanation in the text).

Following this tectonic change, marine incursions were limited and localized from the Late Eocene to the Miocene (Fig. 2B). This period corresponds to the early Alpine collision, which affected the internal domains and the eastern parts of the External Crystalline Massifs (e.g. Simon-Labric et al., 2009; Boschetti et al., 2025c). Meanwhile, regional-scale extension developed in the European plate, driven by the Western European Rift system and the opening of the Liguro–Provençal back-arc basin in southeastern France (Fig. 1) (Hippolyte et al., 1993; Séranne et al., 2021; Jolivet et al., 2021; Boschetti et al., 2023). In the eastern basin, the latest compressional phase is recorded by N–S to NW–SE-trending structures associated with the Digne thrust (Figs. 1–2) and final Alpine exhumation between ∼ 12 and 6 Ma (Schwartz et al., 2017).

3.1 Sampling strategy

Sampling sites were carefully selected to characterize both the nature and ages of brittle deformation in the Jurassic and Cretaceous formations of the Vocontian Basin (Fig. 2A). We first targeted sites where normal faults were described as syn-rift faults or veins formed shortly after deposition (Homberg et al., 2013), and where we observed calcite mineralizations. The analysis of these specific sites was expanded to include other types of brittle structures, such as strike-slip and reverse faults, to document the polyphase deformation of the Vocontian Basin. Our sampling targets were further guided using the 1:50 000 scale BRGM geological maps from Die to Sisteron.

3.2 Tectonic and paleostress analysis

To reconstruct the tectonic evolution of brittle deformation in the Vocontian Basin, fault-slip data and other stress indicators, including calcite veins, were measured in the field and collected for U–Pb dating. Local stress states were inferred by inverting fault-slip data following the methodology of Angelier (1990) using the Win-Tensor software (Delvaux and Sperner, 2003). This analysis provided the orientation of the three principal stress axes (σ1, σ2, and σ3) and the shape of the stress ellipsoids defined by the ratio , reflecting the relative magnitudes of the principal stresses. Relative chronology of the reconstructed stress tensors was determined from cross-cutting relationships between successive generations of veins and faults (normal, reverse, or strike-slip faults). Chronology relative to folding was refined by comparing the orientation of faults, veins, and/or associated stress states in their present-day and unfolded configurations. This approach assumes that faults originally formed according to an Andersonian state of stress, with one principal stress axis vertical.

3.3 Calcite U–Pb geochronology

Prior to U–Pb analyses, each polished thick section was petrographically characterized at IPRA (Institut Pluridisciplinaire de Recherche Appliquée) in Pau, France. This involved optical microscopy coupled with cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging to identify multiple calcite generations (Supplement Fig. S1). CL images were acquired using an OPEA Cathodyne system coupled with a Nikon BH2 microscope, operating at an acceleration voltage of 12.5 kV and an intensity of 300–500 mA. U–Pb dating of calcite was performed at IPREM laboratory (Institut des Sciences Analytiques et de Physico-Chimie pour l'Environnement et les Matériaux), following the protocol of Hoareau et al. (2021, 2025). This method employs isotopic mapping of U, Pb, and Th via a continuous ablation process, combined with a virtual spot method to construct Tera-Wasserburg (TW) plots (Hoareau et al., 2021, 2025). Detailed analytical procedure and data processing is provided in the Supplement (Tables S1–S2). The setup used a 257 nm femtosecond laser ablation system (Lambda3, Nexeya, Bordeaux, France), operating at a frequency of 500 Hz with a spot size of 15 µm. Ablation was conducted in a controlled atmosphere composed of helium (600 mL min−1) and nitrogen (10 mL min−1), mixed with argon in the ICPMS. This system was coupled to an HR-ICPMS Element XR (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a jet interface (Donard et al., 2015).

3.4 Burial history

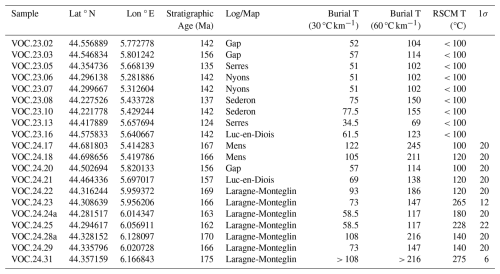

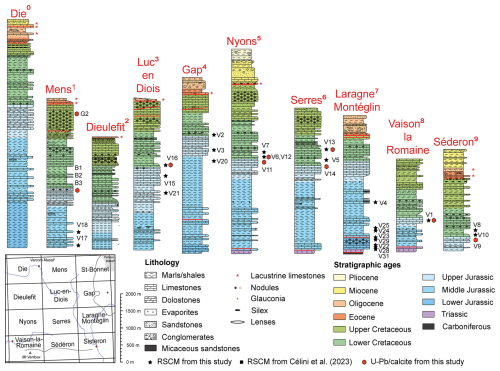

The subsidence history of the Vocontian Basin was reconstructed using stratigraphic sections, including thicknesses and lithologies, from the 1:50 000 scale geological maps of Die, Mens, Dieulefit, Luc-en-Diois, Gap, Nyons, Serres, Laragne-Montéglin, Vaison-la-Romaine, and Séderon, providing basin-wide coverage (Fig. 4). Standard backstripping techniques (Allen and Allen, 2013) were applied. The sedimentary units were first decompacted using coefficients appropriate to their dominant lithology (limestone, marl or clay), with stratigraphic ages inferred from the geological maps. To enable comparison between stratigraphic columns, the stratigraphic data were resampled at 1 Myr intervals, grouped into 5 Myr bins, and interpolated using the 2D spline method.

Figure 4Synthetic stratigraphic sections of the Vocontian Basin reconstructed from stratigraphic thicknesses indicated in explanatory notes of the BRGM geological maps. VX labels refer to sample names V.23.X indicated in the text. Numbers associated to each stratigraphic section are those indicated in Fig. 11.

3.5 RSCM thermometry approach

To determine the peak temperatures reached by sediments in the Vocontian Basin, RSCM analyses were conducted on an initial set of Middle to Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous carbonate samples collected near U–Pb dated calcites (Figs. 2A, 4). A second set of samples was collected further east, in or near, the Authon-Valavoire thrust nappe, a parautochtonous unit at the front of the Digne nappe, where deeper Lower Jurassic strata of the Vocontian are exposed and diapirism has occurred (e.g., Célini et al., 2024). The RSCM approach constrains thermal processes ranging from advanced diagenesis to high-grade metamorphism, covering temperatures from 100 to 650 °C (e.g., Aoya et al., 2010; Kouketsu et al., 2014; Schito et al., 2017). Appropriate calibrations depend on the temperature range and geological context. Here, we applied the calibration of Lahfid et al. (2010) was applied for temperatures between 200 and 340 °C, and the qualitative approach of Saspiturry et al. (2020) for temperatures between 100 and 200 °C. Analyses were performed at the Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières (BRGM; Orléans, France) using a Horiba LABRAM HR instrument with a 514.5 nm solid-state laser source. The laser was focused with a BxFM microscope using a ×100 objective with a numerical aperture of 0.90 and under 0.1 mW at the sample surface.

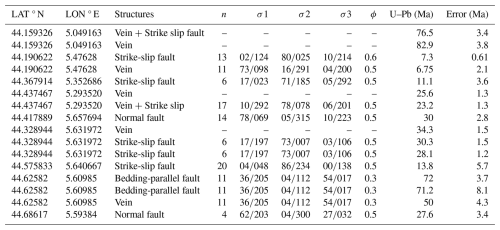

4.1 Microtectonics and paleostress reconstructions

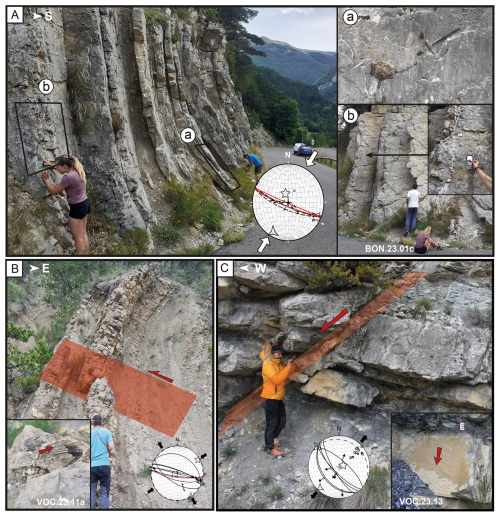

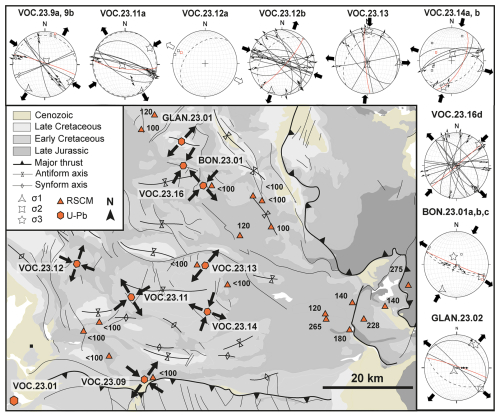

Veins and striated planes associated with folds (Fig. 5A), reverse faults (Fig. 5B) and normal faults (Fig. 5C) were measured and sampled. Stereograms of beddings, fault-slip data, veins and, when relevant, their associated back-tilting state of stress, are presented in Figure 6. When sufficient fault-slip data were available for inversion (minimum of four), the calculated stress axes are reported (Fig. 6; Table 1). In this section, data from samples VOC-23-09a to VOC-23-16d are presented in numerical order, followed by samples BON-23-01 to 03, and GLAN-23-02, which belong to a second, separate field campaign. No measurements were conducted for samples VOC-23-01a and VOC-23-01b, as the sampling area lies within the diapiric structure of the Dentelles de Montmirail (Figs. 2A and 6), potentially introducing local complexities.

Figure 5Examples of tectonic structures for sample BON.23.01 (A), sample VOC.23.11 (B), sample VOC.23.1 (C) with their corresponding stereograms and stress orientations.

Table 1U–Pb dated calcite samples with the location and types of the dated structures (vein or fault indicated as strike-slip, normal or reverse), and their measurements (dip/azimuth).

The sampling area of sample VOC-23-09b is dominated by strike-slip faults, with paleostress inversion indicating a strike-slip regime under NW-SE compression (Fig. 6). At the VOC-23-11a site, where bedding is flat, paleostress reconstructions also reveal a strike-slip regime, involving NE-SW compression and NW-SE extension (Figs. 5B and 6).

Figure 6Simplified geological map of U–Pb dated sampling sites showing stereograms of each dated vein and fault (in orange), together with their associated tectonic structures and stress orientations. Samples with RSCM thermometric constraints (in °C) are also indicated.

Samples VOC-23-12a and VOC-23-12b record distinct deformation patterns. VOC-23-12a comprises calcite veins indicative of WNW-ESE extension, whereas sample VOC-23-12b exhibits similar calcite veins, together with additional strike-slip deformation, consistent with WNW-ESE compression and NNE-SSW extension (Fig. 6). This stress orientation closely matches that of VOC-23-09a and b sites. The geometry of the stress axes relative to bedding dip and orientation suggests that this state of stress postdates folding.

At the VOC-23-13 site, strike-slip faults indicate a paleostress regime characterized by N–S-directed compression and E-W-directed extension (Figs. 5C and 6). Sample VOC-23-14a, a calcite vein spatially associated with sample VOC-23-14b, occurs adjacent to a strike-slip fault with a sinistral component. Paleostress reconstruction indicates a WNW-ESE extension coupled with NNE-SSW compression (Fig. 6).

Sample VOC-23-16d shows calcite veins affected by strike-slip deformation. In contrast, sample VOC-23-12b shows only post-vein strike-slip deformation. Paleostress analysis indicates NW-SE-directed extension (Fig. 6). Samples BON-23-01a and BON-23-01b consist of striated calcite affected by layer-parallel shortening (LPS), interpreted as flexural slip related to folding (Lacombe et al., 2021) (Figs. 5A and 6). Sample BON-23-01c, a calcite vein formed within the same fold, is interpreted to have formed during fold growth. Paleostress reconstruction at the Bonneval outcrop indicates N20° E-directed compression associated with the formation of the N110° E-trending fold (Figs. 5A and 6). Finally, the GLAN-23-02 outcrop exhibits a normal fault consistent with NE-SW-oriented extension.

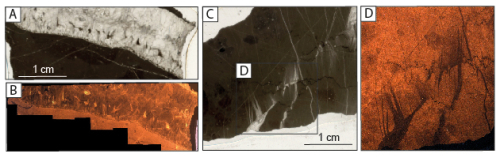

4.2 Petrography of calcite samples

In total, 15 samples were dated in this study: 6 veins (VOC-23-01a, 01b, 09b, 12a, 14b and BON-23-03) and 9 striated fault planes (VOC-23-9a, 11a, 12b, 13, 14a, 16d, BON-23-01, 02 and GLAN-23-02). Most samples contain blocky to elongate-blocky calcite, ranging from millimetres to centimetres (Fig. 7; VOC-23-01, 9a, 12a, 22b, 13a, 14a, BON-23-01, 02, 03 and GLAN-23-02). These calcites are characterized by homogeneous luminescence, indicating a single-phase growth with no evidence of recrystallization (Figs. 7A and B; S1). Two samples exhibit distinct calcite morphologies. Sample VOC-23-11a contains a centimetric calcite showing a transitional morphology between syntaxial and stretched crystals (Fig. 7C and D), suggesting variable growth orientations and multiple crack-seal events. Similarly, sample VOC-23-16d displays millimetric to centimetric blocky calcite crosscut by a younger generation of more elongated and stretched calcite (Fig. 7C and D).

4.3 Calcite U–Pb geochronology

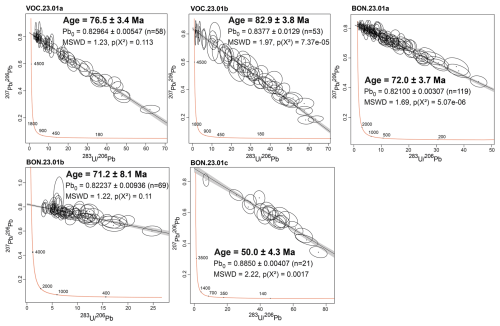

This study presents 16 new calcite U–Pb ages obtained from eight types of brittle structures (Table 1; Figs. 8, 9 and 10). The Tera-Wasserburg diagrams show data well spread along the discordia line, with Mean Squared Weighted Deviation (MSWD) ranging from 1.1 to 1.9, indicating robust and well-resolved age estimates. Three distinct age groups can be identified within the dataset. The first age group corresponds to the Late Cretaceous to Early Eocene interval, based on veins collected in late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous strata in the western part of the basin. In the Dentelles de Montmirail area, ages of 82.9 ± 3.8 Ma (VOC-23-01b) and 76.5 ± 3.4 Ma (VOC-23-01a) were obtained. Further north, in the Die region, fold-related structures associated with N20° E shortening yielded ages of 72.0 ± 3.7 Ma (BON-23-01a), 71.2 ± 8.1 Ma (BON-23-01b), and 50.0 ± 4.3 Ma (BON-23-01c) (Fig. 8).

Figure 8Tera-Wasserburg plots obtained for the first sample group corresponding to faults and veins falling in the Late Cretaceous to Early Eocene interval.

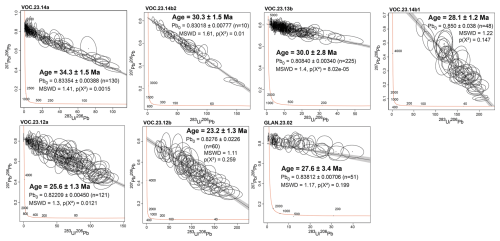

The second age group corresponds to veins and faults formed during the Oligocene. The obtained ages range from 34.3 ± 1.5 Ma (vein VOC.23.14a), 30.3 ± 1.5 Ma (fault VOC.23.14b2), 30.0 ± 2.8 Ma (fault VOC.23.13b), 28.1 ± 1.2 Ma (fault VOC.23.14b1), 25.6 ± 1.3 Ma (vein VOC.23.12a), 23.2 ± 1.3 Ma (fault VOC.23.12b) and 27.6 ± 5.4 Ma (fault GLAN.23.02) (Fig. 9). Most of these fractures correspond to NW-SE to NE-SW extension (Fig. 6). However, sample VOC.23.12b indicates a strike-slip stress regime with NNE-SSW extension and WNW-ESE compression, similar to that inferred from VOC.23.09 (Fig. 6). Calcite veins in VOC.23.12b are of the same type as those in VOC.23.12a.

Figure 9Tera-Wasserburg plots obtained for the second sample group corresponding to Oligocene faults and veins.

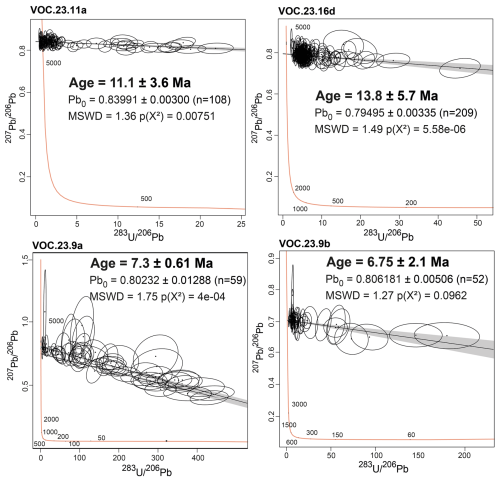

Figure 10Tera-Wasserburg plots obtained for the third sample group corresponding to Miocene faults and veins.

The third age group corresponds to Miocene veins and strike-slip faults hosted in Upper Jurassic-lower Cretaceous carbonates. Two subgroups can be distinguished. The first subgroup, dated to 12.2 ± 3.2 Ma (fault VOC.23.11a) and 12.5 ± 5.2 Ma (fault VOC.23.16d), records a strike-slip regime defined by NE-SW compression and NW-SE extension (Figs. 10 and 6). The second subgroup, with ages of 7.8 ± 0.6 Ma (fault VOC.23.09a) and 7.0 ± 2.2 Ma (vein VOC.23.09b), also reflects a strike-slip regime but with stress orientations indicating NW-SE compression and NE-SW extension (Figs. 10 and 6).

4.4 RSCM thermometry

RSCM data from the first set of Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous carbonates in the central and southern parts of the study area indicate maximum temperatures below 100 °C (VOC-23-01 and VOC-23-16; Table 2). For the second set, reliable temperatures estimates were obtained for 12 samples using an appropriate calibration (Table 2, Fig. 6), which can be divided in two groups. Temperatures measured in Lower to Upper Jurassic strata near Saint Roman and Montmaure, in the Die area, range between 100 and 180 °C (VOC-23-18, VOC-23-17). The lowest temperatures are found near Veynes and close to the Devoluy massif (sample VOC-24-20), in Sigoyer village (samples VOC-23-02, VOC-23-03), and in the upper stratigraphic unit of the Authon-Valavoire nappe (VOC-24-28), and in the eastern part of the basin, below the Digne nappe (sample VOC-24-29). The higher bound of RSCM temperatures, reaching up to 170 °C, is measured in samples VOC-24-24a and 33, both located near diapiric structures of “Rocher de Hongrie” (Célini et al., 2024). These values align with previously reported temperatures of 140–200 °C in the vicinity of the same diapir (Célini et al., 2024). The second group characterized by higher temperatures between 215 and 275 °C, includes samples located 1 km to the south of Sigoyer (VOC-24-23), within the middle Jurassic strata in the hangingwall of the Authon-Valavoire nappe (VOC-24-25), and in the Lias sequence near the Astoin diapir (VOC-23-31). Temperatures of this second group fall within the temperature range recorded in the Authon-Valavoire nappe, particularly near Astoin, closer to the Digne nappe (Célini et al., 2024). To summarize, our data reveal a thermal contrast between the western and eastern domains of the Vocontian Basin. While the organic matter of upper Jurassic-lower Cretaceous formations remaines thermally immature, deeper Early-Middle-Late Jurassic formations exposed in the eastern part of the Vocontian basin, close to the Authon-Vallavoire and Digne nappes exhibit significantly higher thermal maturity, with RSCM temperatures exceeding 180 °C and reaching up to 275 °C. A similar increase in RSCM temperatures between the Upper Jurassic-Early Cretaceous and deeper stratigraphic units of the Early-Middle Jurassic has also been documented in stratigraphic sections of the Digne Nappe (Célini et al., 2022; Balansa et al., 2023).

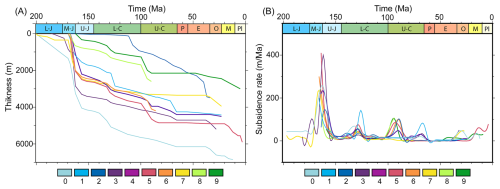

4.5 Burial histories and temperatures reached in the basin

Burial histories for the Vocontian Basin are presented in Fig. 11. Each curve represents the burial evolution within the basin, reconstructed from stratigraphic thicknesses indicated in explanatory notes of the BRGM geological maps covering the Vocontian Basin. The data indicate that total sediment accumulation reached a maximum of 6–7 km since the Early Jurassic. This is shown by the decompacted thicknesses estimated at 6800 m in the Die region and 5900 m near Nyons, in the northern and western sectors of the basin, respectively. In contrast, areas lacking exposures of Lower Jurassic series such as Vaison-la-Romaine, show reduced total subsidence of around 2500 m. Despite these differences, most parts of the basin recorded a main phase of burial during the Middle Jurassic (Callovian, ∼ 160 Ma), associated with the widespread deposition of marls and shales of the “Terres Noires”, typical of the External Alps. During this period, about 2 km of “Terres Noires” accumulated with rates of 200–400 m Myr−1. Following the Middle Jurassic, the burial rates decreased but continued through the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous. A second phase of accelerated subsidence took place during the Early Cretaceous, around 130 Ma (Hauterivian), documented in the Mens section by the deposition of about 700 m of marls and limestones (Fig. 4). A third major burial phase, dated to 100–90 Ma (Fig. 11), is recorded in 6 of the 10 stratigraphic sections (Fig. 11). This phase is characterized by increasing siliciclastic influx, revealed by the deposition of 700–800 m alternating sandstones, marls and limestones (e.g., Nyons, Sédéron, Vaison-la-Romaine). The Gap, Laragne-Montéglin, and Mens sections, however, show evidence of erosion rather than sedimentation at this time. These contrasting depositional patterns reveal concurrent uplift in the source regions and structural compartmentalization in the Vocontian Basin (Fig. 11). A last episode of subsidence, reaching 350–500 m (e.g., Die, Laragne) is documented during the Eocene-Oligocene (Fig. 11).

Figure 11(A) Burial history computed based on the synthetic stratigraphic sections shown in Fig. 4. (B) evolution of sediment accumulation rate through time. 0: Die; 1: Dieulefit; 2: Gap; 3: Laragne-Montéglin; 4: Luc-en-Diois; 5: Mens; 6: Nyons; 7: Sédéron; 8: Serre; 9: Vaison-la-Romaine. L: lower, mi: middle; u: upper; J: Jurassic; C: Cretaceous; p: Paleocene; e: Eocene; o: Oligocene; m: Miocene; pl: Pliocene.

The results from this study are put into perspective of the evolution of the Vocontian Basin of south-east France through time. For this, we merge results from structural analysis with corresponding U–Pb calcite ages, and discuss the evolution of the related burial history estimated from the lithological logs, which have been used to infer paleo-thermal gradients. Four main evolutionary stages can be proposed based on these data, which are discussed below.

5.1 The Mesozoic rifting: E–W trend in thermal gradients and low Ca-rich fluid circulation (170–90 Ma)

The Vocontian basin recorded a prolonged phase of subsidence throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous (Fig. 11), which was not associated with a distinct fluid event. This period coincides with the rifting of the European paleomargin as inferred by the thermal evolution of the Pelvoux Variscan crystalline basement to the north (Boschetti et al., 2025a, c), and from the burial history below the Digne Nappe to the east (Célini et al., 2023). This eastern margin of the basin was likely inverted during the late stages of the Alpine collision between 12 and 6 Ma (Schwartz et al., 2017). We distinguish a first major phase of sedimentary burial that occurred during the Callovian-Oxfordian (170–160 Ma), which postdates the necking of the European paleomargin identified in the External Crystalline Massifs (Mohn et al., 2014; Ribes et al., 2020; Dall'Asta et al., 2022) and is synchronous with the opening of the Alpine Tethys (Lemoine et al., 1986; Manatschal and Müntener, 2009). This rifting is recognized in the Vocontian Basin, where it is expressed by WNW-ESE extension (Dardeau et al., 1988; Homberg et al., 2013), but it is not captured in our calcite U–Pb ages. Similar observations can be made for the subsequent Cretaceous extensional phase (∼ 135 Ma), for which no faults of that age are reported. The high temperatures measured in the Digne Nappe at this time are interpreted as reflecting renewed extension on the European margin associated with the opening of the Valaisan domain (Célini et al., 2023), consistent with ongoing burial heating recorded in the Pelvoux massif (Boschetti et al., 2025a, c). This thermal peak coincides with a shift from the Middle Jurassic WNW–ESE extension to NNE–SSW extension during the Barremian-Aptian (Dardeau et al., 1988; de Graciansky and Lemoine, 1988; Homberg et al., 2013). This later extensional phase is recorded not only throughout the Vocontian Basin (Homberg et al., 2013), but also along its margins. Evidence for this later extensional event includes deformation along the Ventoux–Lure fault zone (Beaudoin et al., 1986; Huang, 1988), the formation of large-scale sliding domains on the Vercors platform (Bièvre and Quesne, 2004), and subsidence in east-west-oriented domains along the Ardèche margin during the same period (Cotillon et al., 1979). Our RSCM analyses indicate an increase in peak temperatures toward the east of the Vocontian Basin, where deeper Lower Jurassic stratigraphic strata are exposed (Fig. 6; Table 2). Comparing these temperatures with temperature inferred from burial depths using normal (30 °C km−1) to high (60 °C km−1) geothermal gradients suggests that the eastern sector experienced unsually high to extreme gradients, consistent with increasing crustal thinning in the Vocontian-Valaisan rift segment in this direction (Fig. 6; Table 2). It should be noted that the sharp increase in the geothermal gradients is not solely due to crustal thinning, but is also largely a result of mantle thinning and asthenosphere uplift. The absence of calcite mineralisation in brittle tectonic features at this time, despite specifically targeting potentially related veins, is intriguing. Indeed, evidence of barite, authigenic quartz and pyrite mineralization in the Callovian-Oxfordian shales in the deeper part of the basin is interpreted as reflecting basal fluid flow during syn-rift peak burial in the Middle Cretaceous, as well as brines related to salt diapirs (Guilhaumou et al., 1996). We suggest that the absence of Middle Cretaceous calcites can be explained either by faulting occurring at a depth too shallow for calcite precipitation, or by subsequent burial to 2–3 km in the eastern basin leading to the dissolution of previous Middle Cretaceous calcites due to changing physical conditions (e.g., pH and temperature). In addition, mechanical decoupling in the Triassic salt layer during extension may have focused fluid flow, so that mineralized fluids of this age are detectable only locally, near the emergence of salt diapirs.

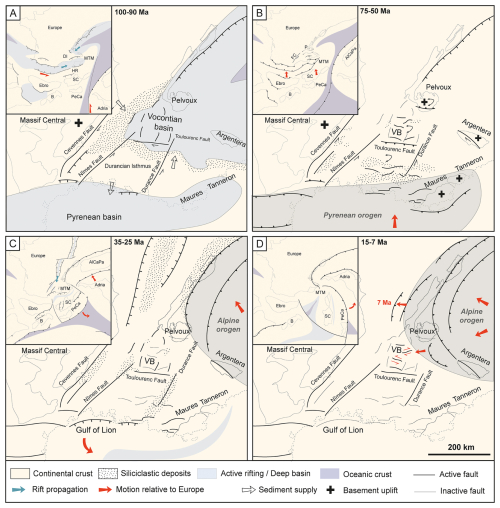

A third depositional phase occurred around 100–90 Ma, in agreement with syn-faulting deposits along the Clausis and Glandage fault systems in the Vocontian/Dévoluy basin (Figs. 11, 3) (Gidon et al., 1970) and with strike-slip activity along the Toulourenc faults in the Ventoux-Lure massif (Montenat et al., 2004). Regionally, this tectonic phase coincides with strike-slip movements along the Cevennes, Nîmes and Durance faults (Montenat et al., 2004; Parizot et al., 2022), potentially associated with local compression related to diapiric movement at 95–90 Ma (Bilau et al., 2023b) and normal faulting reported in Provence (Zeboudj et al., 2025). This episode is a response of the continental rifting between Iberia-Ebro and European plates, and the formation of the Pyrenean rift system (Angrand and Mouthereau, 2021) (Fig. 12A). Strike-slip movements along inherited faults (Cevennes, Nîmes, Durance faults) were associated with oblique extension accommodated by overlapping rift segments in the Pyrenean and Vocontian basins (Fig. 12). This complex tectonic setting likely triggered the emergence of continental blocks that can explain the abundance of sandstone deposits during this period in the Vocontian basin (Figs. 4 and 11). This interpretation aligns with the documented formation of an uplifted structure in Provence during the Albian-Cenomanian, known as the Durancian Isthmus (Combes, 1990; Guyonnet-Benaize et al., 2010; Chanvry et al., 2020, Marchand et al., 2021). Cooling and exhumation in the French Massif Central to the west are also documented from 120–90 Ma (Olivetti et al., 2016), which may have contributed to feeding of the Vocontian basin during this period (Fig. 12A). Although this period is synchronous with the onset of Adria/Europe convergence (e.g., Le Breton et al., 2021; Angrand and Mouthereau, 2021; Boschetti et al., 2025a, b, c), the impact of contraction in the Alps on the evolution Vocontian Basin remains to be assessed.

Figure 12Regional tectonic and paleogeographical reconstitutions of SE France showing the evolution of the Vocontian Basin (VB) since the Middle Cretaceous (modified after Boschetti et al., 2025b). (A) Rifting in overlapping Pyrenean-Vocontian rift segments at 110–90 Ma. (B) Pyrenean-Provençal collision phase from 75 to 50 Ma. (C) Opening of the West European Rift and onset of Alpine foreland fold and thrust belt tectonics. (D) Alpine collision and westward propagation of deformation front. SC: Corsica-Sardinia; B: Baleares; C: Chartreuse; V: Vercors.

5.2 Post-Mid Cretaceous evolution: U–Pb/calcite dating record of multiple Pyrenean-Provençal collision events (90–34 Ma)

The oldest calcite U–Pb ages of 84.6 ± 2.4 Ma and 77.7 ± 2.9 Ma, reported in the Jurassic strata forming the wall of the Suzette diapir (Dentelles de Montmirail) align with the onset of the Pyrenean-Provençal collision around 84 Ma (Angrand and Mouthereau, 2021; Mouthereau et al., 2014; Muñoz, 1992; Teixell et al., 2018; Ford et al., 2022). These old calcite ages may reflect halokinetic movement of the Suzette diapir in response to far-field stresses that triggered tectonic inversion and exhumation all over Europe (Mouthereau et al., 2021). These ages can also be related to a deformation event in the Dévoluy massif affecting the Early Cretaceous units, linked to E–W-directed folding and erosion dated to Coniacian-Santonian (Fig. 3B) (ca. 85 Ma) (Flandrin, 1966; Lemoine, 1972; Gidon et al., 1970), or the end of diapiric movement in southern Provence (Wicker and Ford, 2021). Younger U Pb ages of 72.0 ± 3.7 and 71.2 ± 8.1 Ma associated with N20° E shortening coincides with the intensification of the Pyrenees exhumation at 75–70 Ma (Mouthereau et al., 2014), a phase that is regionally recorded across southeastern France by a cooling event documented from the Pelvoux to the Maures-Tanneron massifs (Fig. 12A) (Boschetti et al., 2025a, b). It is also recognized in the region associated with the sinistral reactivation of the Cevennes fault around 76 Ma (Parizot et al., 2021). The Pyrenean-Provençal collision is therefore well represented in the Vocontian Basin.

Our data also resolve a younger N20° E-directed contractional stage dated at 50.0 ± 4.3 Ma (Fig. 6) that we link to the main Pyrenan-Provençal collision phase. It is recognized in other U Pb age dataset from Provence (Zeboudj et al., 2025), and corresponds to a north-south compression spanning from 59 to 34 Ma regarded as the culmination of the Pyrenean-Provençal collision caused by plate-scale dynamic changes (Bestani et al., 2016; Balansa et al., 2022; Vacherat et al., 2016; Mouthereau et al., 2014, 2021) (Fig. 12B). In northwestern Europe, the Eocene also heralds the onset of the West European Rift (WER), which was active until the Oligocene and just precedes the opening of the Gulf of Lion (e.g. Séranne, 1999; Dèzes et al., 2004; Mouthereau et al., 2021).

5.3 Oligocene rifting related to the West European Rift development (35–23 Ma)

The WER stage is represented in our dataset by eight U Pb dates ranging from 30.4 ± 2.7 to 24.3 ± 1.3 Ma associated with NW–SE to NE–SW extension (Fig. 12C). They coincide with the extensional phase (35–23 Ma) documented in Provence, Western Alps, Eastern Pyrenees, and Valencia Trough (Merle and Michon, 2021; Ziegler and Dèzes, 2006). The Late Eocene-Early Oligocene period also coincides with the onset of the Alpine foreland (Ford et al., 1999). The flexural bending of the European margin caused by Alpine loading likely increased extensional stresses in the foreland, where the WER formed, however the available data are insufficient to draw definitive conclusions. From Chattian-Aquitanian times, at ca. 23 Ma, the opening of the Gulf of Lion and of the Ligurian basin (e.g., Séranne, 1999; Jolivet et al., 1999, 2021) initiated following the demise of the WER suggesting a tectonic relationship between these two rifting events (Mouthereau et al., 2021) (Fig. 12C). In our study area, the shallow depth of the iso-velocity contour Vs = 4.2 km s−1, considered to be a proxy for the Moho (Schwartz et al., 2024), and the 3D geological modelling (Bienveignant et al., 2024), confirms a significant crustal thinning in the Valence-Rhône depression, where structures related to the WER are preserved (Fig. S2 in the Supplement). The excellent preservation of the Oligocene-Miocene extensional phase in our dataset suggests a positive feedback between crustal thinning (Fig. S2 in the Supplement) and physical conditions that became favourable for calcite precipitation at shallower depths, as the basin was progressively exhumed following Late Cretaceous shortening.

5.4 Alpine collision and fold and thrust belt propagation (< 16 Ma)

The youngest calcite U Pb ages of 12.2 ± 3.2, 12.5 ± 5.2, 7.8 ± 0.6 and 7.0 ± 2.2 Ma are associated with NE–SW compression. This result agrees with the westward propagation of the Alpine deformation front, which migrated forelandward from 16 to 7 Ma in the Vercors massif (Bilau et al., 2023a; Mai Yung Sen et al., 2025) to the north of the Vocontian Basin (Fig. 12D). This timing also coincides with the exhumation of Alpine basement, such as the Belledonne and Pelvoux massifs, which accelerated at ca. 12 Ma (e.g. Beucher et al., 2012; Girault et al., 2022; Boschetti et al., 2025a). This age range is also in agreement with the Digne Nappe emplacement at 13–9 Ma (Schwartz et al., 2017) and folds and thrusts development in the frontal southern Alps between 18.2 ± 1.1 and 3.16 ± 0.47 Ma obtained (Bauer et al., 2025; Tigroudja et al., 2025).

The goal of this study was to provide a refined chronology of deformation in the Vocontian Basin using an approach combining U–Pb calcite geochronology, RSCM thermometry, and subsidence analysis. First, this study highlights the absence of mid-Cretaceous syn-rift calcites associated with the opening of the Vocontian Basin. This is possibly related to dissolution during subsequent burial, or reflect the localization of fluid flow and strain in the basal Triassic salt layer during the mid-Cretaceous extension. The temporal distribution of dated brittle structures reveals three main deformation episodes: (1) Late Cretaceous to Paleocene calcite precipitation associated with Pyrenean-Provençal convergence and diapirism; (2) Oligocene extensional phases tied to the West European Rift opening; and (3) Miocene strike-slip reactivation and contraction linked to the Alpine orogeny. These events are superimposed onto a long-term subsidence history that records major burial phases during the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Thermal data from RSCM analyses delineate a sharp eastward increase in geothermal gradients, suggesting enhanced crustal thinning and diapiric activity in the eastern part of the basin. This work highlights a good coherence of the local deformation inferred from calcite U–Pb dating and paleostress analysis, and the regional tectonic evolution.

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article is(are) available in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/se-17-35-2026-supplement.

LB, the corresponding author, led the field investigations, conducted data analysis and interpretation, and prepared the initial manuscript draft. MP contributed to field investigations, performed data analysis, and assisted with manuscript writing. FM participated in field investigations, contributed to data interpretation, and helped with writing. GH carried out the U–Pb data analysis and contributed to the writing. SS and YR both participated in field investigations and writing. DB contributed to data interpretation and discussion, while AL performed the RSCM analysis and took part in writing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Authors would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and BRGM for funding this project.

This study was funded by a scholarship from the Ministry of Higher Education awarded to LB through the SDU2E doctoral school at Toulouse University, and by funding from the BRGM “RGF-Alpes et Bassins du Sud-Est” programme.

This paper was edited by Petr Jeřábek and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Allen, P. A. and Allen, J. R.: Basin analysis: Principles and application to petroleum play assessment, John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Angelier, J.: Inversion of field data in fault tectonics to obtain the regional stress – III. A new rapid direct inversion method by analytical means, Geophysical Journal International, 103, 363–376, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.1990.tb01777.x, 1990.

Angrand, P. and Mouthereau, F.: Evolution of the Alpine orogenic belts in the Western Mediterranean region as resolved by the kinematics of the Europe-Africa diffuse plate boundary, BSGF-Earth Sciences Bulletin, 192, 42, https://doi.org/10.1051/bsgf/2021031, 2021.

Aoya, M., Kouketsu, Y., Endo, S., Shimizu, H., Mizukami, T., Nakamura, D., and Wallis, S.: Extending the applicability of the Raman carbonaceous‐material geothermometer using data from contact metamorphic rocks, Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 28, 895–914, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1314.2010.00896.x, 2010.

Balansa, J., Espurt, N., Hippolyte, J. C., Philip, J., and Caritg, S.: Structural evolution of the superimposed Provençal and Subalpine fold-thrust belts (SE France), Earth-Science Reviews, 227, 103972, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103972, 2022.

Balansa, J., Lahfid, A., Espurt, N., Hippolyte, J. C., Henry, P., Caritg, S., and Fasentieux, B.: Unraveling the eroded units of mountain belts using RSCM thermometry and cross-section balancing: example of the southwestern French Alps, International Journal of Earth Sciences, 112, 443–458, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-022-02257-3, 2023.

Bauer, R., Corsini, M., Matonti, C., Bosch, D., Bruguier, O., and Issautier, B.: The role of Cretaceous tectonics in the present-day architecture of the Nice arc (Western Subalpine foreland, France), Journal of Structural Geology, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2025.105538, 2025.

Beaudoin, B., Friès, G., Joseph, P., Bouchet, R., and Cabrol, C.: Tectonique synsédimentaire crétacée à l'ouest de la Durance (S.-E. France), Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences, Série 2, Mécanique, Physique, Chimie, Sciences de l'univers, Sciences de la Terre, 303, 713–718, 1986.

Bellanger, M., Augier, R., Bellahsen, N., Jolivet, L., Monié, P., Baudin, T., and Beyssac, O.: Shortening of the European Dauphinois margin (Oisans Massif, Western Alps): New insights from RSCM maximum temperature estimates and 40Ar/39Ar in situ dating, Journal of Geodynamics, 83, 37–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jog.2014.09.004, 2015.

Bergerat, F.: Stress fields in the European platform at the time of Africa‐Eurasia collision. Tectonics, 6, 99–132, https://doi.org/10.1029/TC006i002p00099, 1987.

Bestani, L., Espurt, N., Lamarche, J., Bellier, O., and Hollender, F.: Reconstruction of the Provence Chain evolution, southeastern France, Tectonics, 35, 1506–1525, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016TC004115, 2016.

Beucher, R., van der Beek, P., Braun, J., and Batt, G. E.: Exhumation and relief development in the Pelvoux and Dora-Maira massifs (Western Alps) assessed by spectral analysis and inversion of thermochronological age transects, Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, 117, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JF002240, 2012.

Bièvre, G. and Quesne, D.:Synsedimentary collapse on a carbonate platform margin μ (lower Barremian, southern Vercors, SE France), Geodiversitas, 26, 169–184, 2004.

Bienveignant, D., Nouibat, A., Sue, C., Rolland, Y., Schwartz, S., Bernet, M., Dumont, T., Nomade, J., Caritg, S., and Walpersdorf, A.: Shaping the crustal structure of the SW-Alpine Foreland: Insight from 3D modeling, Tectonophysics, 889, 230471, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2024.230471, 2024.

Bilau, A., Bienveignant, D., Rolland, Y., Schwartz, S., Godeau, N., Guihou, A., Deschamps, P., Mangenot, X., Brigaud, B., Boschetti, L., and Dumont, T.: The Tertiary structuration of the Western Subalpine foreland deciphered by calcite-filled faults and veins, Earth-Science Reviews, 236, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.104270, 2023.

Bilau, A., Rolland, Y., Dumont, T., Schwartz, S., Godeau, N., Guihou, A., and Deschamps, P.: Early onset of Pyrenean collision (97–90 Ma) evidenced by U–Pb dating on calcite (Provence, SE France), Terra Nova, 35, 413-423, https://doi.org/10.1111/ter.12665, 2004 2023b.

Boschetti, L., Schwartz, S., Rolland, Y., Dumont, T., and Nouibat, A.: A new tomographic-petrological model for the Ligurian-Provence back-arc basin (North-Western Mediterranean Sea), Tectonophysics, 230111, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2023.230111, 2023.

Boschetti, L., Mouthereau, F., Schwartz, S., Rolland, Y., Bernet, M., Balvay, M., N, Cogné., and Lahfid, A.: Thermochronology of the western Alps (Pelvoux massif) reveals the longterm multiphase tectonic history of the European paleomargin, Tectonics, 44, e2024TC008498, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024TC008498, 2025a.

Boschetti, L., Rolland, Y., Mouthereau, F., Schwartz, S., Milesi, G., Munch, P., Bernet, M., Balvay, M., Thiéblemont, D., Bonno, M., Martin, C., and Monié, P.: Thermochronology of the Maures-Tanneron crystalline basement: insights for SW Europe Triassic to Miocene tectonic history, Swiss J. Geosci., 118, 14, https://doi.org/10.1186/s00015-025-00485-8, 2025b.

Boschetti, L., Boullerne, C., Rolland, Y., Schwartz, S., Milesi, G., Bienveignant, D., Macret, E., Charpentier, D., Munch, P., Mercadier, J., Iemmolo, A., Lanari, P., Rossi, M., and Mouthereau, F.: Shear zone memory revealed by in-situ Rb-Sr and 40Ar/39Ar dating of Pyrenean and Alpine tectonic phases in the external Alps, Lithos, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2025.108168, 2025c.

Célini, N.: Le rôle des évaporites dans l'évolution tectonique du front alpin: le cas de la nappe de Digne, Doctoral dissertation, Université de Pau et des Pays de l'Adour, https://univ-pau.hal.science/tel-03252548/ (last access: 07 June 2021), 2020.

Célini, N., Mouthereau, F., Lahfid, A., Gout, C., and Callot, J. P.: Rift thermal inheritance in the SW Alps (France): insights from RSCM thermometry and 1D thermal numerical modelling, EGUsphere, 2022, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2022-949, 2022.

Célini, N., Mouthereau, F., Lahfid, A., Gout, C., and Callot, J.-P.: Rift thermal inheritance in the SW Alps (France): insights from RSCM thermometry and 1D thermal numerical modelling, Solid Earth, 14, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.5194/se-14-1-2023, 2023.

Célini, N., Pichat, A., Mouthereau, F., Ringenbach, J. C., and Callot, J. P.: Along-strike variations of structural style in the external Western Alps (France): Review, insights from analogue models and the role of salt, Journal of Structural Geology, 179, 105048, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2023.105048, 2024.

Chanvry, E., Marchand, E., Lopez, M., Séranne, M., Le Saout, G., and Vinches, M.: Tectonic and climate control on allochthonous bauxite deposition. Example from the mid-Cretaceous Villeveyrac basin, southern France, Sedimentary Geology, 407, 105727, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2020.105727, 2020.

Combes, P. J.: Typologie, cadre géodynamique et genèse des bauxites françaises, Geodinamica Acta, 4, 91–109, https://doi.org/10.1080/09853111.1990.11105202, 1990.

Cotillon, P., Ferry, S., Busnardo, R., Lafarge, D., and Renaud, B.: Synthèse stratigraphique et paléogéographique sur les faciès urgoniens du Sud de l'Ardèche et du Nord du Gard (France SE), Geobios, 12, 121–139, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-6995(79)80055-8, 1979.

Dall'Asta, N., Hoareau, G., Manatschal, G., Centrella, S., Denèle, Y., Ribes, C., and Kalifi, A.: Structural and petrological characteristics of a Jurassic detachment fault from the Mont-Blanc massif (Col du Bonhomme area, France), Journal of Structural Geology, 159, 104593, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2022.104593, 2022.

Dardeau, G., Atrops, F., Fortwengler, D., De Graciansky, P. C., and Marchand, D.: Jeux de blocs et tectonique distensive au Callovien et a l'Oxfordien dans le bassin du Sud-Est de la France, Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 4, 771–777, 1988.

Debelmas, J.: La zone subbriançonnaise et la zone valaisanne savoyarde dans le cadre de la tectonique des plaques, Géologie Alpine, 77, 3–8, 2001.

De Graciansky, P. C. and Lemoine, M.: Early Cretaceous extensional tectonics in the southwestern French Alps; a consequence of North-Atlantic rifting during Tethyan spreading, Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 4, 733–737, https://doi.org/10.2113/gssgfbull.IV.5.733, 1988.

Delvaux, D. and Sperner, B.: New aspects of tectonic stress inversion with reference to the TENSOR program, GeoscienceWorld, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.212.01.06, 2003.

Debrand-Passard, S., Courbouleix, S., and Lienhardt, M. J.: Synthèse géologique du Sud-Est de la France, volume 1: Stratigraphie et paléogéographie, Mém. BRGM, 125, ISBN 9782715950306, 1984.

Dèzes, P., Schmid, S. M., and Ziegler, P. A.: Evolution of the European Cenozoic Rift System: interaction of the Alpine and Pyrenean orogens with their foreland lithosphere, Tectonophysics, 389, 1–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2004.06.011, 2004.

Donard, A., Pottin, A. C., Pointurier, F., and Pécheyran, C.: Determination of relative rare earth element distributions in very small quantities of uranium ore concentrates using femtosecond UV laser ablation–SF-ICP-MS coupling, Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry, 30, 2420–2428, 2015.

Espurt, N., Angrand, P., Teixell, A., Labaume, P., Ford, M., de Saint Blanquat, M., and Chevrot, S.: Crustal-scale balanced cross-section and restorations of the Central Pyrenean belt (Nestes-Cinca transect): Highlighting the structural control of Variscan belt and Permian-Mesozoic rift systems on mountain building, Tectonophysics, 764, 25–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2019.04.026, 2019.

Flandrin, J.: Sur l'âge des principaux traits structuraux du Diois et des Baronnies, Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 7, 376–386, https://doi.org/10.2113/gssgfbull.S7-VIII.3.376, 1966.

Ford, M. and Lickorish, W. H.: Foreland basin evolution around the western Alpine Arc, Geological Society, London, 39–63, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2004.221.01.04, 2004.

Ford, M., Lickorish, W. H., and Kusznir, N. J.: Tertiary foreland sedimentation in the southern Subalpine chains, SE France: a geodynamic analysis, Basin Research, 11, 315–336, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2117.1999.00103.x, 1999.

Ford, M., Masini, E., Vergés, J., Pik, R., Ternois, S., Léger, J., Dielforder, A., Frasca, G., Grool, A., Vinciguerra, C., and Bernard, T.: Evolution of a low convergence collisional orogen: a review of Pyrenean orogenesis. BSGF-Earth Sciences Bulletin, 193, 19, https://doi.org/10.1051/bsgf/2022018, 2022.

Gidon, M., Arnaud, H., Pairis, J.L., Aprahamian, J., and Uselle, J.P.: Les déformations tectoniques superposées du Dévoluy méridional (Hautes-Alpes), Géologie Alpine, 46, 87–110, 1970.

Girault, J.B., Bellahsen, N., Bernet, M., Pik, R., Loget, N., Lasseur, E., Rosenberg, C.L., Balvay, M., and Sonnet, M.: Exhumation of the Western Alpine collisional wedge: New thermochronological data, Tectonophysics, 822, 229155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2021.229155, 2022.

Guilhaumou, N., Touray, J. C., Perthuisot, V., and Roure, F.: Palaeocirculation in the basin of southeastern France sub-alpine range: a synthesis from fluid inclusions studies, Marine and Petroleum Geology, 13, 695–706, https://doi.org/10.1016/0264-8172(95)00064-X, 1996.

Guyonnet-Benaize, C., Lamarche, J., Masse, J. P., Villeneuve, M., and Viseur, S.: 3D structural modelling of small-deformations in poly-phase faults pattern. Application to the Mid-Cretaceous Durance uplift, Provence (SE France), Journal of Geodynamics, 50, 81–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jog.2010.03.003, 2010.

Hoareau, G., Claverie, F., Pecheyran, C., Paroissin, C., Grignard, P.-A., Motte, G., Chailan, O., and Girard, J.-P.: Direct U–Pb dating of carbonates from micron-scale femtosecond laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry images using robust regression, Geochronology, 3, 67–87, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-3-67-2021, 2021.

Hoareau, G., Claverie, F., Pecheyran, C., Barbotin, G., Perk, M., Beaudoin, N. E., Lacroix, B., and Rasbury, E. T.: The virtual-spot approach: a simple method for image U–Pb carbonate geochronology by high-repetition-rate LA-ICP-MS, Geochronology, 7, 387–407, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-7-387-2025, 2025.

Homberg, C., Schnyder, J., and Benzaggagh, M.: Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous faulting in the Southeastern French Basin: does it reflect a tectonic reorganization?, Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, 184, 501–514, https://doi.org/10.2113/gssgfbull.184.4-5.501, 2013.

Hippolyte, J. C., Angelier, J., Bergerat, F., Nury, D., and Guieu, G.: Tectonic-stratigraphic record of paleostress time changes in the Oligocene basins of the Provence, southern France, Tectonophysics, 226, 15–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(93)90108-V, 1993

Huang, Q.: Geometry and tectonic significance of Albian sedimentary dykes in the Sisteron area, SE France, J. Struct. Geol., 10, 453–462, 1988.

Jolivet, L., Frizon de Lamotte, D., Mascle, A., and Séranne, M.: The Mediterranean basins: Tertiary extension within the Alpine orogen – An introduction. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 156, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1999.156.01.02, 1999.

Jolivet, L., Menant, A., Roche, V., Le Pourhiet, L., Maillard, A., Augier, R., Do Couto, D., Gorini, C., Thinon, I., and Canva, A.: Transfer zones in Mediterranean back-arc regions and tear faults, Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 192, https://doi.org/10.1051/bsgf/2021006, 2021.

Joseph, P., Beaudoin, B., Sempere, T., and Maillart, J.: Vallées sous-marines et systèmes d'épandages carbonatés du Berriasien vocontien (Alpes méridionales françaises), Bull. Soc. Geol. Fr., 8, 363–374, 1988.

Kouketsu, Y., Mizukami, T., Mori, H., Endo, S., Aoya, M., Hara, H., Nakamura, D., and Wallis, S.: A new approach to develop the R aman carbonaceous material geothermometer for low-grade metamorphism using peak width, Island Arc., 23, 33–50, https://doi.org/10.1111/iar.12057, 2014.

Lacombe, O., and Jolivet, L.: Structural and kinematic relationships between Corsica and the Pyrenees‐Provence domain at the time of the Pyrenean orogeny, Tectonics, 24, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004TC001673, 2005.

Lacombe, O., Beaudoin, N. E., Hoareau, G., Labeur, A., Pecheyran, C., and Callot, J.-P.: Dating folding beyond folding, from layer-parallel shortening to fold tightening, using mesostructures: lessons from the Apennines, Pyrenees, and Rocky Mountains, Solid Earth, 12, 2145–2157, https://doi.org/10.5194/se-12-2145-2021, 2021.

Lahfid, A., Beyssac, O., Deville, E., Negro, F., Chopin, C., and Goffé, B.: Evolution of the Raman spectrum of carbonaceous material in low-grade metasediments of the Glarus Alps (Switzerland). Terra nova, 22(5), 354-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3121.2010.00956.x, 2010.

Le Breton, E., Brune, S., Ustaszewski, K., Zahirovic, S., Seton, M., and Müller, R. D.: Kinematics and extent of the Piemont–Liguria Basin – implications for subduction processes in the Alps, Solid Earth, 12, 885–913, https://doi.org/10.5194/se-12-885-2021, 2021.

Lemoine, M.: Rythme et modalités des plissements superposés dans les chaînes subalpines méridionales des Alpes occidentales françaises, Geologische Rundschau, 61, 975–1010, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01820902, 1972.

Lemoine, M., Bas, T., Arnaud-Vanneau, A., Arnaud, H., Dumont, T., Gidon, M., Bourbon, M., de Graciansky, P.-C., Rudkiewicz, J.-L., Megard-Galli, J., and Tricart, P.: The continental margin of the Mesozoic Tethys in the Western Alps, Mar. Petrol. Geol., 3, 179–199, https://doi.org/10.1016/0264-8172(86)90044-9, 1986.

Lemoine, M., Tricart, P., and Boillot, G.: Ultramafic and gabbroic ocean floor of the Ligurian Tethys (Alps, Corsica, Apennines): in search for a genetic model, Geology, 15, 622–625, 1987.

Mai Yung Sen, V., Rolland, Y., Valla, P. G., Jaillet, S., Bruguier, O., Bienveignant, D., and Robert, X.: Fold‐and‐Thrust Belt and Early Alpine Relief Recorded by Calcite U–Pb Dating of an Uplifted Paleo‐Canyon (Vercors Massif, France), Terra Nova, 37(3), 148–156, https://doi.org/10.1111/ter.12761, 2025.

Manatschal, G. and Müntener, O.: A type sequence across an ancient magma-poor ocean–continent transition: the example of the western Alpine Tethys ophiolites, Tectonophysics, 473, 4–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2008.07.021, 2009.

Marchand, E., Séranne, M., Bruguier, O., and Vinches, M.: LA-ICP-MS dating of detrital zircon grains from the Cretaceous allochthonous bauxites of Languedoc (south of France): Provenance and geodynamic consequences, Basin Research, 33, 270–290, https://doi.org/10.1111/bre.12465, 2021.

Merle, O. and Michon, L.: The formation of the West European Rift; a new model as exemplified by the Massif Central area, Bulletin de la Societé géologique de France, 172, 213–221, https://doi.org/10.2113/172.2.213, 2021.

Mohn, G., Manatschal, G., Beltrando, M., and Haupert, I.: The role of rift-inherited hyper-extension in Alpine-type orogens, Terra Nova, 26, 347–353, https://doi.org/10.1111/ter.12104, 2014.

Montenat, C., Janin, M. C., and Barrier, P.: L'accident du Toulourenc: une limite Tectonique entre la plate-forme provençale et le Bassin vocontien à l'Aptien–Albien (SE France), Comptes Rendus Géoscience, 336, 1301–1310, 2004.

Mouthereau, F., Filleaudeau, P.Y., Vacherat, A., Pik, R., Lacombe, O., Fellin, M.G., Castelltort, S., Christophoul, F., and Masini, E.: Placing limits to shortening evolution in the Pyrenees: Role of margin architecture and implications for the Iberia/Europe convergence, Tectonics, 33, 2283–2314, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014TC003663, 2014.

Mouthereau, F., Angrand, P., Jourdon, A., Ternois, S., Fillon, C., Calassou, S., Chevrot, S., Ford, M., Jolivet, L., Manatschal, G., and Masini, E.: Cenozoic mountain building and topographic evolution in Western Europe: impact of billions of years of lithosphere evolution and plate kinematics, BSGF-Earth Sciences Bulletin, 192, 56, https://doi.org/10.1051/bsgf/2021040, 2021.

Muñoz, J. A.: Evolution of a continental collision belt: ECORS-Pyrenees crustal balanced cross-section. In Thrust tectonics, Dordrecht, Springer Netherlands, 235–246, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-3066-0_21, 1992.

Olivetti, V., Godard, V., Bellier, O., and Aster Team.: Cenozoic rejuvenation events of Massif Central topography (France): Insights from cosmogenic denudation rates and river profiles, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 444, 179–191, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2016.03.049, 2016.

Parizot, O., Missenard, Y., Haurine, F., Blaise, T., Barbarand, J., Benedicto, A., and Sarda, P.: When did the Pyrenean shortening end? Insight from U–Pb geochronology of syn-faulting calcite (Corbières area, France), Terra Nova, 33, 551–559, https://doi.org/10.1111/ter.12547, 2021.

Parizot, O., Missenard, Y., Barbarand, J., Blaise, T., Benedicto, A., Haurine, F., and Sarda, P.: How sensitive are intraplate inherited structures? Insight from the Cévennes Fault System (Languedoc, SE France), Geological Magazine, 159, 2082–2094, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756822000152, 2022.

Philippe, Y., Deville, E., and Mascle, A.: Thin-skinned inversion tectonics at oblique basin margins: example of the western Vercors and Chartreuse Subalpine massifs (SE France), Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 134, 239–262, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1998.134.01.11, 1998.

Ribes, C., Ghienne, J.F., Manatschal, G., Dall’Asta, N., Stockli, D.F., Galster, F., Gillard, M., and Karner, G.D.: The Grès Singuliers of the Mont Blanc region (France and Switzerland): stratigraphic response to rifting and crustal necking in the Alpine Tethys, International Journal of Earth Sciences, 109, 2325–2352, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-020-01902-z, 2020.

Roure, F., Brun, J. P., Colletta, B., and Van Den Driessche, J.: Geometry and kinematics of extensional structures in the Alpine foreland basin of southeastern France, Journal of Structural Geology, 14, 503–519, https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8141(92)90153-N, 1992.

Saspiturry, N., Lahfid, A., Baudin, T., Guillou‐Frottier, L., Razin, P., Issautier, B., Le Bayon, B., Serrano, O., Lagabrielle, Y., and Corre, B.: Paleogeothermal gradients across an inverted hyperextended rift system: Example of the Mauléon Fossil Rift (Western Pyrenees), Tectonics, 39, e2020TC006206, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020TC006206, 2020.

Schito, A., Romano, C., Corrado, S., Grigo, D., and Poe, B.: Diagenetic thermal evolution of organic matter by Raman spectroscopy, Organic Geochemistry, 106, 57–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2016.12.006, 2017.

Schwartz, S., Gautheron, C., Audin, L., Dumont, T., Nomade, J., Barbarand, J., Pinna-Jamme, R., and van der Beek, P.: Foreland exhumation controlled by crustal thickening in the Western Alps, Geology, 45, 139–142, 2017.

Schwartz, S., Rolland, Y., Nouibat, A., Boschetti, L., Bienveignant, D., Dumont, T., Mathey, M., Sue, C.m and Mouthereau, F.: Role of mantle indentation in collisional deformation evidenced by deep geophysical imaging of Western Alps, Communications Earth & Environment, 5, 17, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01180-y, 2024.

Séranne, M.: The Gulf of Lion continental margin (NW Mediterranean) revisited by IBS: an overview. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 156, 15–36, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1999.156.01.03, 1999.

Séranne, M., Couëffé, R., Husson, E., Baral, C., and Villard, J.: The transition from Pyrenean shortening to Gulf of Lion rifting in Languedoc (South France) – A tectonic-sedimentation analysis, BSGF-Earth Sciences Bulletin, 192, 27, https://doi.org/10.1051/bsgf/2021017, 2021.

Simon-Labric, T., Rolland, Y., Dumont, T., Heymes, T., Authemayou, C., Corsini, M., and Fornari, M.: 40Ar/ 39Ar dating of Penninic Front tectonic displacement (W Alps) during the Lower Oligocene (31–34 Ma), Terra Nova, 21, 127–136, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3121.2009.00865.x, 2009.

Stämpfli, G. M., and Borel, G. D.: A plate tectonic model for the Paleozoic and Mesozoic constrained by dynamic plate boundaries and restored synthetic oceanic isochrons, Earth and Planetary science letters, 196, 17–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00588-X, 2002.

Teixell, A., Labaume, P., Ayarza, P., Espurt, N., de Saint Blanquat, M., and Lagabrielle, Y.: Crustal structure and evolution of the Pyrenean-Cantabrian belt: A review and new interpretations from recent concepts and data, Tectonophysics, 724, 146–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2018.01.009, 2018.

Tigroudja, L., Espurt, N., and Scalabrino, B.: Quantifying Miocene thin-and thick-skinned shortening in the Baous thrust system, SW French Alpine Front, Tectonophysics, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2025.230930, 2025.

Trümpy, R.: A possible Jurassic-Cretaceous transform system in the Alps and the Carpathians, GoescienceWorld, https://doi.org/10.1130/SPE218-p93, 1988.

Turco, E., Macchiavelli, C., Mazzoli, S., Schettino, A., and Pierantoni, P. P.: Kinematic evolution of Alpine Corsica in the framework of Mediterranean mountain belts. Tectonophysics, 579, 193–206, 2012.

Vacherat, A., Mouthereau, F., Pik, R., Bellahsen, N., Gautheron, C., Bernet, M., Daudet, M., Balansa, J., Tibari, B., Jamme, R. P., and Radal, J.: Rift-to-collision transition recorded by tectonothermal evolution of the northern Pyrenees, Tectonics, 35, 907–933, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015tc004016, 2016.

Wicker, V. and Ford, M.: Assessment of the tectonic role of the Triassic evaporites in the North Toulon fold-thrust belt, BSGF-Earth Sciences Bulletin, 192, 51, https://doi.org/10.1051/bsgf/2021033, 2021.

Zeboudj, A., Lacombe, O., Beaudoin, N. E., Callot, J. P., Lamarche, J., Guihou, A., and Hoareau, G.: Sequence, duration, rate of deformation and paleostress evolution during fold development: Insights from fractures, calcite twins and U–Pb calcite geochronology in the Mirabeau anticline (SE France), Journal of Structural Geology, 105460, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2025.105460, 2025.

Ziegler, P. A. and Dèzes, P.: Crustal evolution of western and central Europe, European Lithosphere Dynamic, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.MEM.2006.032.01.03, 2006.