the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Quaternary surface ruptures of the inherited mature Yangsan Fault: implications for intraplate earthquakes in southeastern Korea

Sangmin Ha

Hee-Cheol Kang

Seongjun Lee

Yeong Bae Seong

Jeong-Heon Choi

Seok-Jin Kim

Moon Son

Earthquake prediction in intraplate regions, such as the Korean Peninsula, is challenging due to the complexity of fault distributions. This study employed diverse methods and data sources to investigate Quaternary surface rupturing along the Yangsan Fault, aiming to understand its long-term earthquake behavior. Paleoseismic data from the Byeokgye section (7.6 km) of the Yangsan Fault are analyzed to provide insights into earthquake parameters (i.e., timing, displacement, and recurrence intervals) as well as structural patterns. Observations from five trench sites indicate at least six faulting events during the Quaternary, with the most recent surface rupturing occurring approximately 3000 years ago. These events resulted in a cumulative horizontal displacement of 76 m and a maximum estimated magnitude of Mw 6.7–7.1. The average slip rate of 0.13 ± 0.1 mm yr−1 suggests a quasi-periodic model with possible recurrence intervals exceeding 13 000 years. Structural patterns indicate the reactivation of a pre-existing fault core with top-to-the-west geometry, causing a dextral slip with a minor reverse component. This study underscores the several surface ruptures with large earthquakes along the inherited mature Yangsan Fault, since at least the Early Pleistocene, offering critical insights for seismic hazard and a broader understanding of intraplate earthquake dynamics, enhancing earthquake prediction efforts.

- Article

(19844 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Earthquake prediction is challenging, and large earthquakes with surface ruptures significantly damage infrastructure (Geller et al., 1997; Wyss, 1997; Crampin and Gao, 2010; Woith et al., 2018). To predict large earthquakes, it is necessary to identify the pattern of earthquake occurrences, which can be periodic, quasi-periodic, and random (Shimazaki and Nakata, 1980; McCalpin, 2009). Earthquakes can be categorized as interplate (plate boundary) or intraplate (mid-continental) based on their tectonic location (England and Jackson, 2011; Liu and Stein, 2016). Numerous studies have identified relatively “predictable” cycles, patterns, causes, magnitudes, and epicenters in the interplate region, where earthquakes are more frequent, leading to improved earthquake preparedness (e.g., San Andreas Fault, Nankai trough; Powell and Weldon II, 1992; Murray and Langbein, 2006; Smith and Sandwell, 2006; Obara and Kato, 2016; Uchida and Burgmann, 2019).

Large earthquakes in the intraplate region occur less frequently than in the interplate region but can have devastating impacts (e.g., 1556 Huaxian earthquake, Mw 8.0; 1976 Tangshan earthquake, Mw 7.8; 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquake; 2001 Gujarat earthquake, Mw 7.6; 2011 Virginia earthquake, Mw 5.8; Min et al., 1995; Johnston and Schweig, 1996; Hough et al., 2000; Hough and Page, 2011; Wolin et al., 2012). Large intraplate earthquakes have recently received considerable attention and researchers are attempting to understand them based on insights obtained from interplate earthquakes (England and Jackson, 2011; Liu and Stein, 2016; Talwani, 2017). However, intraplate earthquakes exhibit complex spatiotemporal patterns that do not follow general interplate earthquake pattern models (Liu and Stein, 2016; Talwani, 2017). This can partly be explained by the poor catalog due to their slow slip rates (< 1 mm yr−1) and long recurrence intervals (> 1000 years). The faults in the intraplate region have a more complex distribution than those in the interplate region and tend to be selectively reactivated in response to far-field stress (Liu and Stein, 2016; Talwani, 2017).

To understand the unpredictable patterns of intraplate earthquakes, it is necessary not only to collect robust paleoseismic data but also to find connections between paleoseismic data and structural features such as the relationship between geometry and the in situ stress regime, as well as fault kinematics controlled by the pre-existing structure. Korea, located on the intraplate, has experienced very few damaging earthquakes since instrumented seismic monitoring began. However, medium-sized earthquakes have caused damage near the epicenters and raised earthquake awareness (e.g., the 2016 Gyeongju earthquake, the 2017 Pohang earthquake; Kim et al., 2018; Woo et al., 2019). Despite calls for realistic earthquake preparedness, seismic research in South Korea remains at an early stage compared to neighboring countries on plate boundaries, such as Japan and Taiwan. Basic seismic hazard assessment requires the acquisition of robust paleoseismic data (Reiter, 1990; Gurpinar, 2005; McCalpin, 2009). The reduction of paleoseismic uncertainty necessitates an expanded dataset, which in turn demands a significant volume of data. Various methods can be employed to efficiently detect Quaternary faults and obtain robust paleoseismic parameters. Although this need has been recognized, until recently, paleoseismology studies in Korea have mostly been based on a single trench except a few recent studies (e.g., Kim et al., 2023). Earthquakes in South Korea appear to follow the quasi-periodic behavior of intraplate earthquakes (Kim and Lee, 2023). To unravel this quasi-periodic pattern of an intraplate fault, it is necessary to collect paleoseismic data from multiple faults with Quaternary surface rupturing to complete the puzzle. The Yangsan Fault is one of the vital intraplate faults in Korea that could solve this puzzle, with recent reports of Quaternary surface rupture (e.g., Kim et al., 2023), but many unknowns remain. In this study, we try to provide clues to the pattern of the earthquake behavior of the Yangsan Fault.

This study seeks to trace the distribution of the Quaternary surface rupturing during the Holocene and obtain fundamental paleoseismic data on the Yangsan Fault. To achieve this, we apply multiple methods to identify traces of Quaternary surface ruptures with higher accuracy and interpret a highly robust paleoseismic synthesis from the extensive data collected (e.g., five trenches and about ∼ 30 numerical ages). We focus on the Byeokgye section (Kim et al., 2022) in the southern part of the northern Yangsan Fault, a major tectonic line in southeastern Korea, to create a geological map and select trench sites through fieldwork. This study aims to reveal (1) robust paleoseismic data, filling gaps in prior surface rupture documentation, (2) Quaternary reactivation features of intraplate mature fault zones, and (3) the spatiotemporal surface rupturing pattern of the Yangsan Fault. The results of this study can be used as essential inputs for seismic hazard assessment and to understand the Quaternary rupturing patterns of the Yangsan Fault.

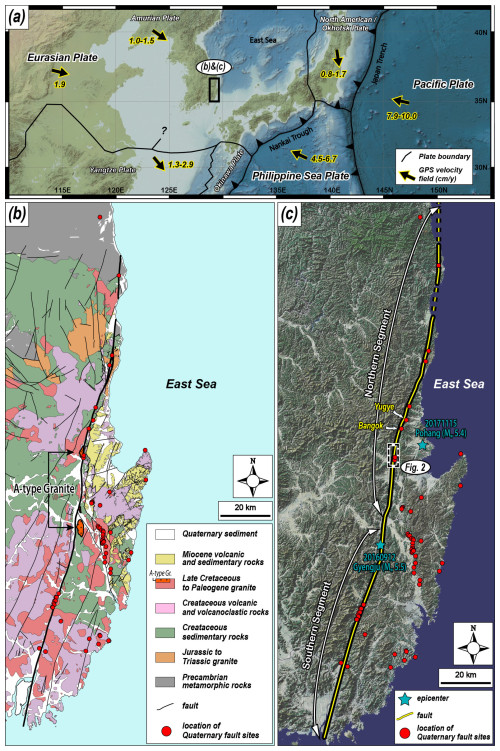

2.1 Regional seismotectonic setting of Korea

The Korean Peninsula is located at the eastern margin of the Eurasian Plate (Fig. 1a; e.g., Bird, 2003; Calais et al., 2006; Argus et al., 2010; Ashurkov et al., 2011). The relative frequency of earthquakes in Korea is low compared with other regions on nearby plate boundaries, such as Japan, China, Taiwan, and the Philippines (KMA, 2022). While paleoseismology, archeoseismology, and historical seismicity studies indicate that large (M≥7) earthquakes occurred in the past, medium-sized (M≥5) instrumental earthquakes have been occasionally observed since the onset of seismic instrument measurements (Lee, 1998; Lee and Yang, 2006; Han et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016, 2018, 2020b). Currently, the Korean Peninsula is under a maximum horizontal stress in the E–W to ENE–WSW direction, which is the result of the combined effects of the subduction of the Pacific and Philippine Sea plates and eastward-propagating far-field stress from India–Eurasia collision (Park et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2016; Kuwahara et al., 2021). GNSS studies show that the Korean Peninsula has a velocity field of about 3 cm yr−1 towards the WNW direction (Ansari and Bae, 2020; Sohn et al., 2021; Kim and Bae, 2023). Recent short-term (2-year) GNSS studies on the Yangsan Fault suggest that the fault appears to be stable, with blocks on both sides of the fault moving in the same direction and at the same displacement rate (Kim and Bae, 2023).

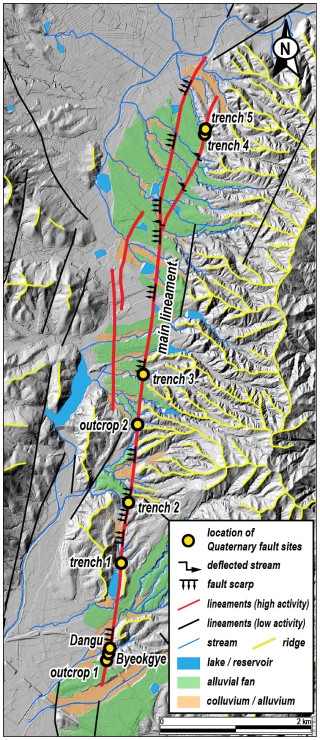

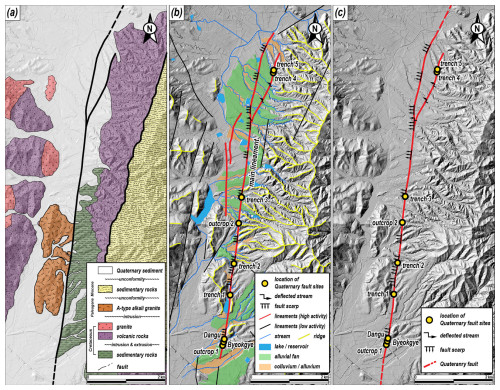

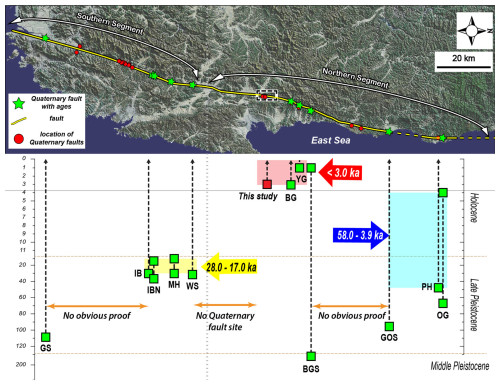

Figure 1Regional study area maps. (a) Tectonic map of East Asia showing plate boundaries and their velocities (modified from DeMets et al., 1990, 1994; Seno et al., 1993, 1996; Heki et al., 1999; Bird, 2003; O'Neill et al., 2005; Schellart and Rawlinson, 2010; Kim et al., 2016). The black arrow indicates the moving direction of each plate. (b) Regional geological map of SE Korea (modified from Chang et al., 1990; Kim et al., 1998; Hwang et al., 2007a, b; Son et al., 2015; Song, 2015; Kang et al., 2018). The thick black line indicates the Yangsan Fault, and the 21 km dextral offset of the Yangsan Fault is interpreted by the distribution of A-type granite. (c) Topographic satellite image map of SE Korea and recent epicenters. The Yangsan Fault is divided into two segments (modified from Kim et al., 2022, 2023) and the study area is located in the southern part of the northern segment.

Paleoseismic studies on the Korean Peninsula since the 1990s have revealed that most Quaternary surface ruptures were propagated along major structures in the southeastern part of the peninsula, such as the Yangsan Fault, Ulsan Fault, and Yeonil Tectonic Line (Fig. 1b and c; Kee et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011, 2016; Choi et al., 2012). Since the 2016 Gyeongju earthquake, the Yangsan Fault has drawn increasing attention in various fields, including tectonic geomorphology (Lee et al., 2019; Park and Lee, 2018; Kim and Oh, 2019; Kim et al., 2020c; Kim and Seong, 2021; Hong et al., 2021), fault structure at the outcrop scale and microscale (Woo et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2017; Cheon et al., 2017, 2019, 2020a; Kim et al., 2017a, b, 2020a, 2021, 2022; Ryoo and Cheon, 2019; Gwon et al., 2020), paleoseismology (Lee et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2019; Cheon et al., 2020b; Ko et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2023), and fault chronography (Yang and Lee, 2012; Song et al., 2016, 2019; Sim et al., 2017; Kim and Lee, 2020, 2023). Notably, there are many records of Quaternary surface rupturing with dextral kinematics, which were reactivated along the pre-existing mature (long-lived) Yangsan Fault zone (Cheon et al., 2020a). This fault extends > 200 km on land and is several hundred meters wide, with a prevailing horizontal displacement of > 20 km (Choi et al., 2017; Cheon et al., 2017, 2019, 2020a, b). It underwent multiple stages of deformation with various kinematic senses during the Cretaceous to Cenozoic (Fig. 1b; Chang et al., 1990; Kim, 1992; Chang and Chang, 1998; Chang, 2002; Hwang et al., 2004, 2007a, b; Choi et al., 2009; Cheon et al., 2017, 2019). The dextral horizontal displacement of the fault is approximately 25–35 km in the Cretaceous sedimentary rocks (Chang et al., 1990) and 21.3 km in A-type alkali granite on both sides of the fault (Fig. 1b; Hwang et al., 2004, 2007a, b).

2.2 Geological settings of the Byeokgye section of the Yangsan Fault

The northern Yangsan Fault, located north of Gyeongju at the junction of the Ulsan and Yangsan faults, has documented several Quaternary surface ruptures (Fig. 1b). These surface ruptures caused offsets in alluvial fans, river terraces, and deflected rivers with dextral displacements of 0.43–2.82 km (Kyung, 2003; Choi et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2019; Han et al., 2021; Ko et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022; Lee, 2023). Recent earthquakes in Pohang and Gyeongju further underscore the seismic activity of this region. The Byeokgye section, which crosses Gyeongju and Pohang, is located in the southern part of the northern Yangsan Fault, adjacent to the Yugye and Bangok sites to the north (Fig. 1c). In contrast, no Quaternary surface rupture has been identified in the Angang area to the south.

The rocks in the study area are composed of Cretaceous sedimentary, volcanic, and granitic rocks, Paleogene A-type alkaline granite, Middle Miocene sedimentary rocks, and Quaternary sediments (Fig. 2a). The A-type alkaline granite, used as a dextral offset marker for the Yangsan Fault, is distributed on the west side of the fault in the center of the study area and on the east side in Gyeongju, and the offset is 21.3 km (Fig. 1b; Hwang et al., 2004, 2007a, b). The Middle Miocene sedimentary rocks in the eastern part of the study area are bounded by the western marginal faults of the Miocene Pohang Basin consisting of normal faults and dextral transfer faults (Fig. 2a; Son et al., 2015; Song, 2015). The Quaternary sediments in the study area are widely distributed along streams and valleys, and stratigraphic features cut by Quaternary surface rupturing along the Yangsan Fault are observed in some places (Fig. 2b, c).

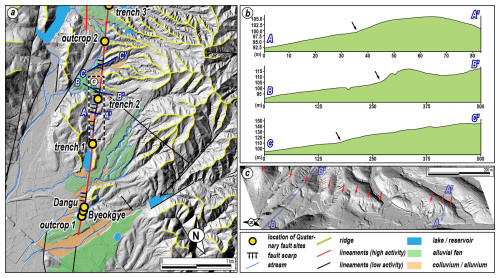

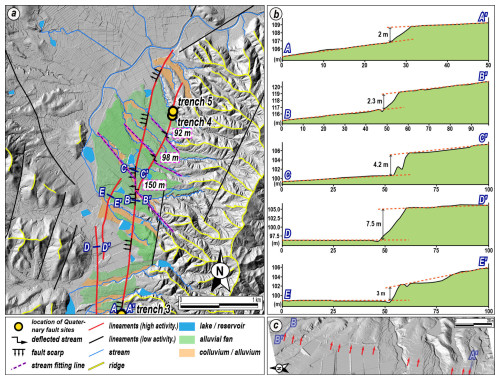

Figure 2Detailed study area maps. (a) Geological map of the study area (modified from Hwang et al., 2007b; Song, 2015). The A-type alkali granite in the study area is used as a marker of the Yangsan Fault's dextral offset. (b) Geomorphological map of the study area (modified from Ha et al., 2022). A fault trace is recognized as an array of fault scarps and deflected streams. (c) Fault trace map of the study area. Two outcrops and five trenches are located in the fault trace.

In the study area, the Byeokgye (outcrop) and Dangu (trench) sites have been reported as records of the Quaternary surface ruptures (Fig. 2; Ryoo et al., 1999; Kee et al., 2009; Choi et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2015). The NNE-striking fault splay identified at the Byeokgye site cuts the Cretaceous felsic dike and Quaternary sediment. Based on the shear bands within the fault gouge, drag folds in the footwall, and sub-horizontal striations, it was interpreted that strike-slip occurred after reverse slip during the Quaternary (Ryoo et al., 1999). The most recent earthquake (MRE) of the Byeokgye site occurred after 75 ± 3 ka, the optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) age of the truncated Quaternary sediments (Choi et al., 2012). The surface ruptures (N10–20° E, 75–79° SE) of the two trenches at the Dangu site have geometric and kinematic features similar to those at the Byeokgye site (Lee et al., 2015). The drag fold, slickenline, and three fault gouge zones observed in the exposed walls indicate that at least three strike-slip events with reverse slip occurred after the deposition of Quaternary sediments. In addition, the MRE of the Dangu site using OSL dating, radiocarbon, and archeological interpretation of artifacts in the Quaternary sediments occurred at 7.5 ± 3 ka (Lee et al., 2015). Recently, Song et al. (2020) excavated a trench 1 km north of the Byeokgye site to identify further records on the Quaternary surface rupturing and attempted paleoseismic interpretation. We set this trench as Trench 1 for a comprehensive interpretation and summarize the results.

3.1 Fault surface rupture tracking and trench siting

Ha et al. (2022) reported a 7.6 km fault trace in the study area through detailed topographic analysis using high-resolution (< 20 cm) lidar images (Fig. 2b). They interpreted the main lineament as a fault scarp with a vertical displacement of 2–4 m and a dextral refraction channel with a horizontal displacement of 50–150 m. In the trench (Trench 1) on the fault trace, the surface rupture cuts through Quaternary sediments. The detailed topography of the study area is described in Appendix A. We conducted fieldwork along this fault trace, trenched it at four further sites, and identified two natural exposures (described in Appendix C).

3.2 Dating methods

3.2.1 Quartz OSL and K-feldspar IRSL dating

For luminescence dating, a total of 36 samples were collected from the five trench walls by inserting light-proof stainless-steel pipes (30 cm long and 5 cm in diameter) into sand-rich layers. The sediment samples were then brought into a subdued darkroom to extract pure quartz and K-feldspar grains. The size fractions of 90–250 µm were first separated by wet sieving. Subsequently, these fractions were treated with 10 % HCl (∼ 1 h) and 10 % H2O2 (∼ 3 h) to remove carbonates and interstitial organic matter. This was followed by density separation using SPT (sodium polytungstate; ρ= 2.61 g cm−3). Pure quartz and K-feldspar extracts were finally prepared by etching the sinking (quartz-rich) and floating (K-feldspar-rich) portions with ∼ 40 % and 10 % HF (∼ 1 h), respectively. The extracts were then rinsed with 10 % HCl to dissolve any fluoride precipitates that may have formed during HF etching. The purity of quartz extracts (i.e., the absence of K-feldspar contamination) was determined by comparing infrared-stimulated luminescence (IRSL) and blue-stimulated luminescence (BSL) signals using three natural and beta-irradiated (20 Gy) aliquots. For all quartz extracts, the IRSL signals were negligible, with IRSL to BSL ratios well below 2 %, indicating that K-feldspar grains were effectively removed through the sample preparation procedure.

The luminescence signals were measured using a conventional Risø reader (model TL/OSL-DA-20) installed at the Korea Basic Science Institute (KBSI). The stimulation light sources were blue LEDs (470 nm, FWHM 20 nm) for quartz and IR LEDs (870 nm, FWHM 40 nm) for K-feldspar. The reader was equipped with a 90Sr/90Y source to deliver beta doses to the sample position at a calibrated dose rate of 0.150 ± 0.002 Gy s−1 (Hansen et al., 2015). The signals were detected through a UV filter (U-340) for quartz OSL and a blue filter pack (a combination of 4 mm Corning 7–59 and 2 mm Schott BG 39) for K-feldspar IRSL.

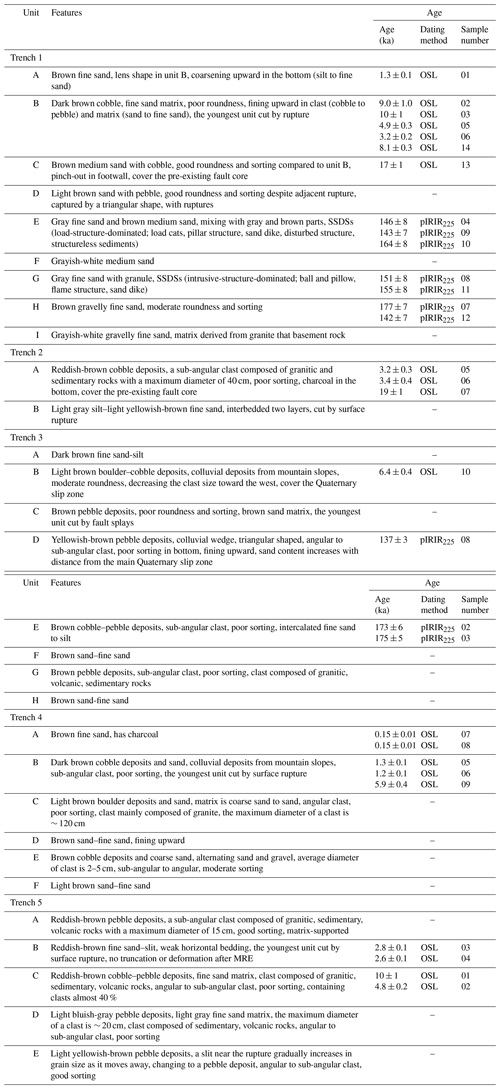

Quartz OSL equivalent dose (De) values were estimated using the single-aliquot regenerative-dose (SAR) procedure (Murray and Wintle, 2000), with preheat conditions for main regeneration and test doses of 260° for 10 s and 220° for 0 s, respectively. Quartz OSL signals in dose saturation (i.e., for samples older than datable age ranges of the quartz OSL dating method) and K-feldspar post-IR IRSL signals, which are well known to have higher dose saturation levels than quartz OSL (Buylaert et al., 2012), were used as samples for De estimation. K-feldspar post-IR IRSL De values were estimated using the SAR procedure suggested by Buylaert et al. (2009), where, after preheating at 250° for 60 s, IRSL signals in K-feldspar were read at 225° for 100 s, immediately followed by lower-temperature (50°) IR stimulation (hereafter, this signal is referred to as pIRIR225). The measured fading rates (g2 d) of the K-feldspar pIRIR225 signals ranged from 0 % dec−1–2 % dec−1, and fading corrections were made using the R package “Luminescence” (Calc_FadingCorr; Kreutzer, 2023) to derive the final pIRIR225 age estimates. The quartz OSL and fading-corrected K-feldspar pIRIR225 ages are summarized in Table 1.

3.2.2 Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating was performed to obtain independent ages and to cross-validate the ages of the sediments. Eight charcoal samples are collected from sediment profiles of Trenches 1, 2, and 4 and analyzed using accelerator mass spectrometry at the Beta Analytic Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory. The 14C age was calibrated to calendar years using the OxCal 4.3 (Bronk Ramsey, 2017) and IntCal 20 (Reimer et al., 2020) atmospheric curves.

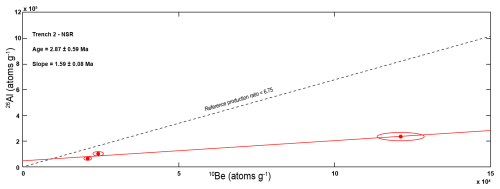

3.2.3 10Be–26Al isochron burial dating

Isochron burial dating is a variation of conventional burial dating methods that constrains the time elapsed since the sediment burial and has been widely used for dating the alluvial sediments of 5.0–0.2 Ma (Granger and Muzikar, 2001). The burial duration was calculated from the difference between the initial Be ratio at the time of burial and the measured ratio of Be (Balco and Rovey, 2008; Erlanger et al., 2012). Unlike traditional simple burial dating, which assumes that the initial ratio is known or the same as the surface production ratio of 6.8, isochron burial dating requires multiple samples with their pre-burial histories (i.e., various initial ratios of Be) to construct an isochron. The initial ratio of Be of the samples at burial depends on the erosion and production rates in the source basin. Thus, we assumed that all the analyzed samples originated from the same basin under steady-state erosion. The pre-burial (i.e., inherited) concentrations of the gravel at the time of burial accumulated with a surface production ratio of 6.8 so that it falls on a line in the plot of 26Al–10Be (Lal, 1991; Granger, 2006; Balco and Rovey, 2008). We used the conventional value of 6.8 for the surface production ratio of Be for the current study, which can vary depending on longitude, latitude, and altitude (Balco and Rovey, 2008). Without considering the pre-burial exposure history, the measured nuclide concentrations of gravel at the same depth should again fall on a line in the plot of 26Al–10Be with a mean life of τpb= 1/(λ26–λ10) (∼ 2.07 Ma) because they have the same post-burial production of 26Al (C26) and 10Be (C10). Thus, the post-burial component can be treated as a constant so that it can be modeled, and the initial ratio of Be (Rinh) can be calculated as

The final time (tb) elapsed since burial can be calculated from the decay of the initial isochron (Rinh) to the isochron of the measured samples (Rm):

3.2.4 ESR dating

Electron spin resonance (ESR) dating of fault rocks is a method used to derive the timing of faulting by measuring the ESR signal in the quartz of a fault gouge (Ikeya et al., 1982; Lee and Schwarcz, 1994). In general, ESR dating has an age detection limit of up to several thousand years (e.g., Lee and Yang, 2003) and is thus helpful for direct dating of the timing of faulting. The ESR signal of quartz grains can be reset when the fault surface is subjected to normal stress of more than 3 MPa and displacements of more than 0.3 m (Kim and Lee, 2020, 2023). These conditions are usually easier to meet at a depth of more than ∼ 100 m than at the surface. Therefore, it is likely that ESR signals from fault gouges currently exposed at the surface are reset at depths and then brought up to the surface (i.e., current position) via uplift. In addition, in the case that the ESR signals are not completely reset during faulting, the ESR ages may indicate the maximum age of MRE. In our study, we use the ESR ages of samples from trenches and fault sites in the study area reported by Kim and Lee (2023) to estimate the number of earthquakes.

3.3 Paleo-stress reconstruction

Paleo-stress reconstruction of Quaternary rupturing was carried out using 20 slickenlines obtained from five trenches. The data were analyzed using Wintensor S/W (v.5.8.5; Delvaux and Sperner, 2003). The type of stress regime is expressed quantitatively using the R′ value: (σ1 is vertical), 2−R (σ2 is vertical), or 2+R (σ3 is vertical); ) (Delvaux et al., 1997).

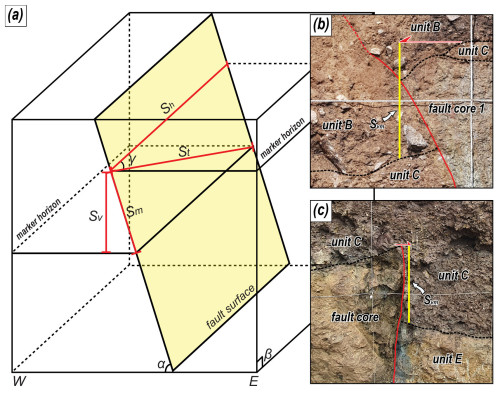

3.4 Displacement and earthquake magnitude estimation

The slickenlines of the main surface rupture and the vertical separation of the Quaternary sediments in the trench wall are used to determine the horizontal displacement of the MRE and the displacement per event. In general, for strike-slip faults like the study area, horizontal displacements must be obtained from 3D trenches or from topography that preserves the displacements almost intact (e.g., Kim et al., 2024; Naik et al., 2024). Using only 2D trenches to obtain displacements or slip rates is uncertain because the sedimentary layers are unlikely to have recorded all earthquakes. Furthermore, deriving the horizontal displacement is challenging when exposed walls are inclined, markers are inclined, or the slip sense is not purely dip-slip or strike-slip (which is almost always the case). In addition, displacements based on fragmentary information, such as bedrock separation and thickness of Quaternary sediments, can be overestimated or underestimated by fault slip motion and the possibility of paleo-topographic relief cannot be ignored. Despite these uncertainties, fault displacement is a necessary factor in earthquake magnitude estimation and is key paleoseismological information, and the displacement obtained from the 2D trench can be used as a minimum value; therefore, the process of collecting or estimating fault displacement is indispensable in paleoseismology. Therefore, correlations based on vertical separation, marker dip angle, angle of the slope wall, fault dip angle, and/or rake of the slickenline are important for estimating the horizontal displacement of a fault (Fig. B1; Xu et al., 2009; Jin et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Gwon et al., 2021). The method of using their relationship to find the horizontal displacement is described in detail in Appendix B.

Variables used for earthquake magnitude estimation include average displacement (Kanamori, 1977), maximum displacement (MD; Bonilla et al., 1984; Wells and Coppersmith, 1994), surface rupture length (Bonilla et al., 1984; Khromovskikh, 1989; Wells and Coppersmith, 1994), rupture area (Wells and Coppersmith, 1994), and surface rupture length × MD (Bonilla et al., 1984; Mason, 1996). However, in Korea, where rupture traces are difficult to find, it is difficult to use surface rupture length or rupture area owing to large uncertainties. Thus, we used MD (horizontal displacement), which is relatively easy to obtain from outcrops and trenches and more reliable. Many previous studies within the intraplate region have applied the empirical relationship of the MD–moment magnitude (Mw) presented by Wells and Coppersmith (1994) (e.g., Patyniak et al., 2017 in Kyrgyzstan; Suzuki et al., 2021 in Mongolia; Ge et al., 2024., in China). We also estimated the maximum earthquake magnitude by applying the MD obtained from the trench to the empirical formula. The rake of slickenlines on the Quaternary slip surface that underwent faulting averages 20° and strike-slip motion is dominant; therefore, we used a corresponding strike-slip fault type of Mw–MD empirical relationship.

4.1 Characteristics of Quaternary faulting in the trench

4.1.1 Trench 1

Trench 1, previously reported by Song et al. (2020) and Ha et al. (2022), is summarized as follows.

It is located on the main lineament, approximately 1 km north of the Byeokgye site (Fig. 2c), within a cultivated field where a narrow 50 m wide N–S-trending valley and a 20 m wide NE-trending valley meet, through which the main lineament passes. To the east of Trench 1, a NE-trending ridge develops, although this is currently difficult to identify due to human modification, while to the west, a hill with a N–S-trending ridge is formed (Fig. A2). Fault scarps are distinctly visible along the main lineament to both the south and north of Trench 1, with small fluvial and colluvial deposits observed on the surface. Nine Quaternary sedimentary units and seven east-dipping splay-slip surfaces (F1–F7) cutting the units are found in the E–W-trending trench wall (Fig. 3). The hanging wall of F6 is the western boundary of a pre-existing fault core more than 2.5 m wide and the footwall of F6 is a 4 m thick Quaternary sedimentary unit overlying the A-type alkali granite. The pre-existing fault core is divided into two zones based on whether it is related to rupturing. Between F6 and F7, the fault core has a 40 cm wide blue fault gouge cutting Quaternary sediments and a weakly developed shear band within the fault gouge. The fault core, on the eastern side of F7, did not cut the Quaternary sediments and consists of a brown to dark gray brecciated zone and a gouge zone more than 2 m wide. The stratigraphic features of the nine units are listed in Table 1, and there are two noteworthy observations: first, the triangular-shaped unit D, characterized by a light brown sandy matrix with better sorting and roundness compared to the surrounding units, is surrounded by slip surfaces (Fig. 3). It indicates that unit D may have been captured by the horizontal displacement of nearby sediments during the faulting event. Second, various types of seismogenic soft-sediment deformation structures (SSDSs) are developed in units E and G (Fig. 3, Fig. 10 in Ha et al., 2022). The orientations of slip surfaces range from N60° W to N28° E, changing from NW- to NE-striking to the east. The F6 fault splay (N01° E, 69° SE) cuts through unit B and the F7 splay (N28° E, 86° SE) is terminated in unit C. F3, F4, and F5 cut through units D, E, and F, respectively, and are terminated under unit C. F1 and F2 cut through units G, H, and I but not through unit F. The rakes of the slickenline observed on F6 measured 15–55°, indicating a dextral slip with a reverse component. Three faulting events are interpreted based on the geometry of the sediments and the kinematics of the slip surface: (1) the first faulting event involves the rupture of F1–F7 after the deposition of units G, H, and I before the deposition of unit F, marking the event 1 horizon. (2) The second faulting event occurred after the deposition of units E and F prior to the deposition of unit C, defining the event 2 horizon, with ruptures affecting faults F3 through F7. During this event, dextral slip along faults F5 and F6 displaced unit D. (3) The third faulting event took place after the deposition of units B and C, with rupture limited to faults F6 and F7.

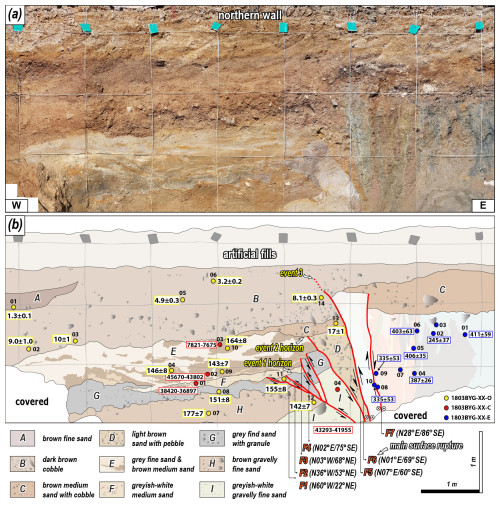

Figure 3(a) Photomosaic of the Trench 1 wall of the northern wall. The colored circles represent samples for age dating. (b) Detailed sketch of the Trench 1 exposed wall. Light gray lines indicate a 1 × 1 m grid. The numbers in the yellow, red, and blue boxes represent OSL and IRSL (ka), radiocarbon (cal yr BP), and ESR (ka) dating results, respectively.

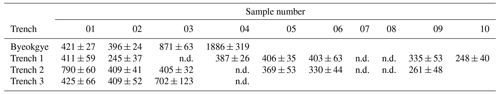

OSL and pIRIR225 ages are presented in Table 1. We also conducted 14C and ESR dating on the trench. Three charcoal samples (1803BYG-01-C, 1803BYG-02-C, and 1803BYG-03-C) were collected from unit E and one charcoal sample (1803BYG-04-C) was collected from unit I for radiocarbon dating. The results of samples 1803BYG-01-C and 1803BYG-02-C are 38 420–36 897 and 45 670–43 802 cal yr BP, respectively (Table 2). However, the ages of these two samples are near the upper limit of the radiocarbon dates and are stratigraphically contradictory, with the lower layer being younger than the upper layer. The age of 1803BYG-03-C (7821–7675 cal yr BP) from the upper part of unit E is inconsistent with the OSL age (1803BYG-10-O: ∼ 164 ka). It is possible that liquefaction in unit E caused a disturbance in the sediments and that the radiocarbon and OSL dates do not indicate the exact depositional timing. In addition, the radiocarbon age of 43 292–41 955 cal yr BP for the sample from unit I is near the upper limit of the radiocarbon ages and is thus subject to error. In particular, it is younger than K-feldspar pIRIR225 (177 ± 7 ka (1803BYG-07-O)) from unit H, making it unlikely that this age is indicative of the depositional age of unit I. The main surface rupture cut unit B, and the MRE using the OSL age of unit B is < 3.2 ± 0.2 ka (1803BYG-06-O; Table 1, Fig. 3). The geometry and cross-cutting relationship between the Quaternary sediments and the seven surface ruptures indicate that a pre-existing fault core was reactivated during the Quaternary, resulting in at least three faulting events (Fig. 3, Fig. 9 in Song et al., 2020): the first (antepenultimate earthquake, AE) occurred at < 142 ± 4 ka (1803BYG-12-O), the second (penultimate earthquake, PE) at > 17 ± 1 ka (1803BYG-13-O), and the third is the MRE (Table 1, Fig. 3). For ESR dating, 36 fault gouge samples were collected from the eastern side of F7, and ESR dating was performed on 10 of them (1810BYG-01 to 1810BYG-10-E) (Fig. 3). The dates of each sample are presented in Table 3. The weighted average ESR ages of the samples from the same fault viscose band are 245 ± 37 ka (1810BYG-02-E, 1810BYG-10-E), 406 ± 35 ka (1810BYG-01-E, 1810BYG-05-E, 1810BYG-06-E), 387 ± 26 ka (1810BYG-04-E), and 335 ± 53 ka (1810BYG-04-E) (Table 3). Samples with dose-saturated ESR signals (1810BYG-03-E, 1810BYG-07-E, and 1810BYG-08-E) are excluded from the weighted average age calculations. Considering the error, the timing of faulting events using ESR ages at these sites can be determined to be 406 ± 35 and 245 ± 37 ka.

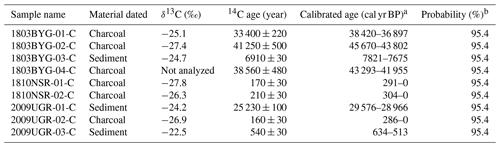

Table 214C dating results.

a Calibration used the database INTCAL13 (Reimer et al., 2020). b Probability method (Bronk Ramsey, 2017).

4.1.2 Trench 2

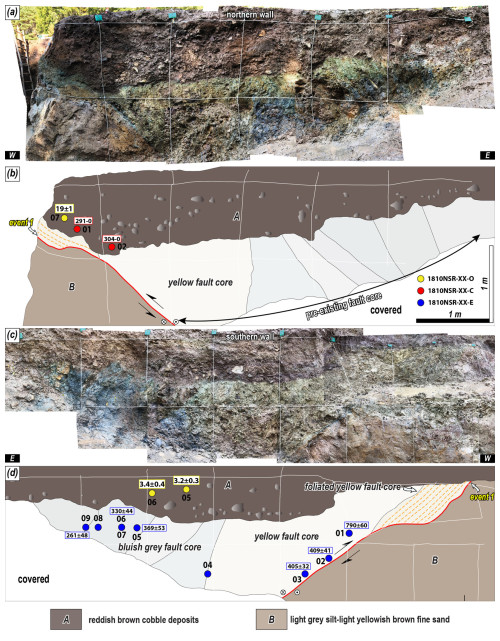

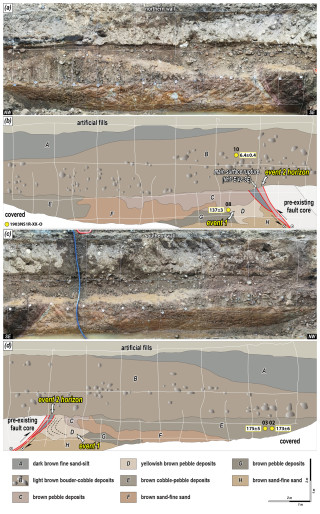

Trench 2 is located on the main lineament 0.8 km north of Trench 1 (Fig. 2c), within a colluvial area where fault scarps extend continuously along the main lineament to the south and north. Just north of Trench 2, the transition to an alluvial fan is clearly visible where the mountain ridge meets the main lineament. The 25 m wide valley surface contains partially developed colluvial sediments and deposits from small streams and gullies. Two Quaternary deposits are observed in Trench 2, along a low-angle Quaternary slip surface (N02° E, 38° SE) intersecting the Quaternary deposits on the exposed wall (Fig. 4). The minimum 6 m wide fault core of the hanging wall is composed of mature fault rocks. The fault core is divided into yellow and bluish gray (Fig. 4). Foliation developed within the yellow fault core, which abutted the Quaternary slip surface in the upper part of the wall. The Quaternary slip surface cuts unit B, displaying thrusting of the hanging wall's pre-existing fault core, while unit A overlies both features. Unit A has a loose matrix and relatively low consolidation compared to the underlying unit B and overlies the pre-existing fault core (Table 1). The slickenline on the Quaternary slip surface shows a dextral slip with a minor reverse component. Only one faulting event is recognized, in which the Quaternary slip surface cuts through unit B, and unit A overlies it (Fig. 5b, d).

Figure 4Photomosaic of the Trench 2 exposed wall of the (a) northern and (c) southern walls. The colored circles represent samples for age dating. Detailed sketch of the Trench 2 exposed wall of the (b) northern wall and (d) southern wall. White lines indicate a 1 m × 1 m grid. The numbers in the yellow, red, and blue boxes represent OSL and IRSL (ka), radiocarbon (cal yr BP), and ESR (ka) dating results, respectively.

The OSL ages of unit A, which covers the rupture, are 3.4 ± 0.4 ka (1810NSR-06) and 3.2 ± 0.3 ka (1810NSR-05) at the southern wall and 19 ± 1 ka (1810NSR-07) at the northern wall (Table 1). The radiocarbon ages of the charcoal in unit A are 291–0 and 304–0 cal yr BP (Table 2), making them much younger than the OSL age from unit A. Radiocarbon dates do not indicate when the charcoal was deposited with the sediment but when the tree died after being rooted in the ground. The OSL results indicate a depositional age of 3.4 ± 0.4 ka for unit A, which is not cut by the rupture, so the MRE of the surface rupture in Trench 2 is interpreted to be before 3.4 ± 0.4 ka. The ESR ages obtained from the fault gouge are higher than the depositional ages of the sediments cut by the rupture (Table 3). The ESR ages suggest that the quartz ESR signal in the fault gouge was not fully initialized during faulting. Nevertheless, the ESR ages roughly cluster into four periods: 790 ± 60 ka (1810NSR-01-E), 407 ± 37 ka (1810NSR-02, 03-E), 350 ± 49 ka (1810NSR-05, 06-E), and 261 ± 48 ka (1810NSR-09-E).

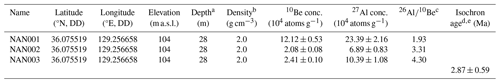

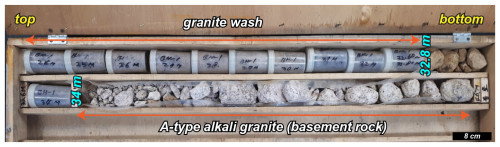

To estimate the thickness of the Quaternary sediments and the cumulative vertical displacement of the Quaternary slip, drilled sediments were sampled from the footwall along the Quaternary slip surface (Fig. D1). The Quaternary sediments extend to a depth of approximately 32.8 m, underlain by a granite wash (1.2 m thick) of Paleogene A-type alkali granite and a subsequent fault damage zone of the granite exists at its base (Fig. D1). Therefore, the vertical separation caused by the Quaternary rupture in Trench 2 is at least 34 m. However, the vertical separation is a paleo-topographic relief difference that may have been caused by the strike-slip movement of the Quaternary slip. Cosmogenic 10Be–26Al isochron dating of the granite wash underlying the Quaternary sediments yielded a burial age of 2871 ± 593 ka, indicating that the thick Quaternary sediments started to be deposited after 2871 ± 593 ka (Table 4).

4.1.3 Trench 3

Trench 3 is located on the main lineament extending 1.7 km north of Trench 2 (Fig. 2c), within a cultivated field next to a wide road at the mouth of a broad basin. Fault scarps along the main lineament extend both south and north of Trench 3. This trench marks the northernmost point where the transition to the alluvial fan is observed where the mountain ridge meets the main lineament; beyond this point, fault scarps continue to develop on the alluvial fan surface. Eight Quaternary sedimentary units and three fault splays are identified in the trench wall (Fig. 5, Table 1). The hanging wall of the Quaternary slip zone, which cut through Quaternary sediments, is composed of a pre-existing fault core. Excavation revealed a fault core at least 20 m wide. The fault gouge zone that cut the Quaternary sediments is narrower than 5 cm at the bottom of the wall and widens to 40 cm at the top of the wall; it is divided into a grayish-white gouge zone and a red gouge zone by color and slip surface. The red fault gouge zone is almost entirely composed of clay; however, there are numerous uncrushed quartz and rock fragments within the grayish-white gouge zone. The characteristics of the eight units are shown in Table 1. Unit D is a colluvial wedge that indicates a paleo-earthquake (Fig. 5, Table 1). Brown sand to fine (units F and H) and brown gravel (units C, E, and G) deposits are in the trench wall. These features can be attributed to environmental factors, such as deposition due to repeated rainfall, flooding, or seismic events due to repeated seismic motion. The Quaternary slip zone cuts through unit C, including unit D, a colluvial wedge, and is covered by unit B. The slickenline observed on the fault splays indicates a dextral slip with a small reverse component. There are at least two estimated faulting events in this exposed wall: event 1, which formed a colluvial wedge, and event 2, which cut the colluvial wedge (Fig. 5).

Figure 5Photomosaic of the Trench 3 wall of the (a) northern wall and (c) southern wall. The colored circles represent samples for age dating. Detailed sketch of the Trench 3 wall of the (b) northern and (d) southern walls. White lines indicate a 1 × 1 m grid. The dotted black line reveals the bedding trace. The numbers in the yellow, red, and blue boxes represent OSL and IRSL (ka), radiocarbon (cal yr BP), and ESR (ka) dating results, respectively.

The pIRIR225 ages of samples 1903NR1R-02 and 1903NR1R-03-O from unit E at the southern wall are 173 ± 6 ka and 175 ± 5 ka, respectively. In contrast, the pIRIR225 age of 1903NR1R-08-O from unit D, which is the colluvial wedge that directly indicates the timing of a faulting event, shows that the deposit formed at 137 ± 3 ka (Table 1). Additionally, sample 1903NR1R-10-O from unit B, which covers the rupture, is dated as 6.4 ± 0.4 ka. These findings suggest that the first surface rupture occurred at 137 ± 3 ka, as indicated by the colluvial wedge, and the next surface rupture occurred before 6.4 ± 0.4 ka, indicated by the event 2 horizon. The youngest ESR age for the fault gouge is 409 ± 52 ka (1903NR1R-02-E, Table 3). However, since the quartz ESR signal in the fault zone may not have fully reset during faulting, this age implies that the faulting event occurred at or after 409 ± 52 ka. The ESR ages cluster into two time periods: 417 ± 59 ka (1903NR1R-01, 1903NR1R-02-E) and 702 ± 123 ka (1903NR1R-03-E).

4.1.4 Trench 4

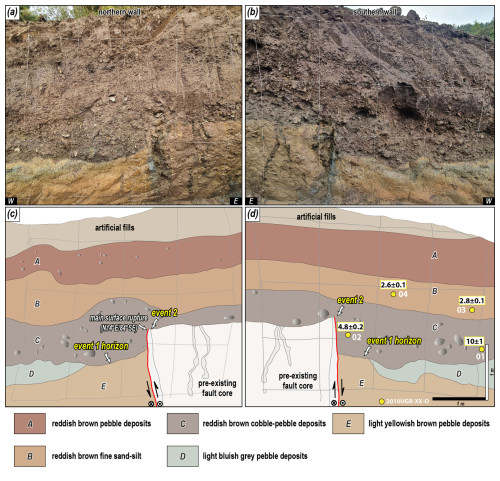

Trench 4 is situated on a NE-striking eastern branch lineament from the main lineament, which stretches 2.8 km north of Trench 3 (Fig. 2c). South of Trench 4, three continuous dextrally deflected streams follow the branching lineament, with smaller displacements identified further north. Trench 4 lies at the edge of an alluvial fan near a hillslope, with two features separated by a stream. Within the trench wall, five Quaternary sedimentary units are cut by a surface rupture (Fig. 6, Table 1). The hanging wall of the Quaternary fault splay includes a pre-existing fault core at least 5 m wide at the time of excavation. Adjacent to the Quaternary sediments, a 20 cm wide fault gouge zone developed, characterized by yellowish-brown and reddish-brown gouges. Units A and B exhibit horizontal to sub-horizontal bedding, while the bedding of units C–F tilts westward, with dips of up to 50° near the surface rupture, becoming shallower to the west (Fig. 6, Table 1). The difference in bedding orientations indicates an angular unconformity between unit B and units C–F. A surface rupture, covered by unit A, cuts through all of units C–F, including the unconformity, but does not extend through all of unit B. The slickenlines observed on the fault splay indicate dextral slip with a minor reverse component. At least two faulting events are inferred from the exposed wall: the first faulting event (PE) caused the tilting of units C–F after deposition (event 1 horizon), and the MRE occurred during the deposition of unit B, following the formation of the angular unconformity (Fig. 6).

Figure 6Photomosaic of the Trench 4 wall of the (a) northern and (c) southern walls. The colored circles represent samples for age dating. Detailed sketch of the Trench 4 wall of the (b) northern and (d) southern walls. Gray lines indicate a 1 × 1 m grid. The numbers in the yellow, red, and blue boxes represent OSL and IRSL (ka), radiocarbon (cal yr BP), and ESR (ka) dating results, respectively.

We collected five samples from the northern wall of units A and B. The OSL age of 5.9 ± 0.4 ka was obtained from 2009UGR-09-O, which is cut by the rupture. For the remaining four samples that are not cut by the rupture, the oldest OSL age is 1.3 ± 0.1 ka, recorded for 2009UGR-05-O (Table 1). Additionally, samples were collected from units F (2009UGR-01-C) and A (2009UGR-02-C) for radiocarbon dating (Table 2). The radiocarbon age of the charcoal from 2009UGR-02-C is 160 ± 30 cal yr BP, which aligns with the OSL age of 0.15 ± 0.01 ka for the sediment containing the charcoal (2009UGR-07-O), strongly indicating that unit A was deposited at this time. Based on comprehensive dating analyses, the MRE for this trench occurred between 5.9 ± 0.4–1.3 ± 0.1 ka, as the faulting event took place during the continuous deposition of unit B.

4.1.5 Trench 5

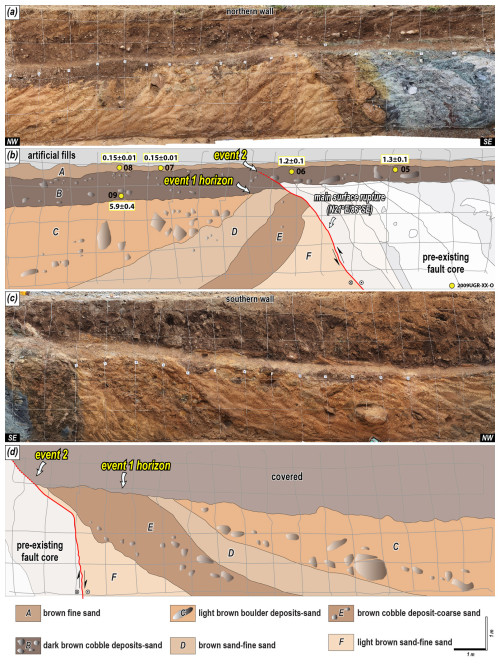

Trench 5 is located 40 m north of Trench 4. Because of its proximity, Trench 5 shares identical topographic characteristics with Trench 4, except that it lies on the margins of a hillslope instead of on an alluvial fan. The trench wall contains five Quaternary sedimentary units, cut by one fault splay (Fig. 7). The overall appearance of the exposed wall is similar to that of Trench 4. The hanging wall of the fault splay that cut the Quaternary sediments consists of a pre-existing fault core at least 20 m wide. Where it abuts the Quaternary sediments, a 10 cm wide light gray fault gouge developed, which changes to a yellowish-gray fault gouge with yellow clay mixed toward the top. Units A–C show sub-horizontal bedding, units D and E show westward-dipping bedding, and there is an angular disconformity between units C and D. Trenches 4 and 5 are almost the same because they are adjacent, with units A–C in Trench 5 matching units A and B in Trench 4 and units D and E in Trench 5 matching units C–F in Trench 4. The reddish-brown sediments in the upper part of Trench 5 appear to be thicker than in Trench 4 because it is the tip of a hillslope. The Quaternary fault splay cut unit C but failed to cut unit B. The slickenline observed on the high-angle Quaternary fault splay indicates a dextral slip with a small reverse component. At least two faulting events are estimated based on the same angular unconformity as in Trench 4. Event 1 caused units D and E to tilt, which cut them (event 1 horizon, Fig. 7). Event 2 occurred during the deposition of unit C, which failed to cut into unit B.

Figure 7Photomosaic of the (a) northern and (b) southern walls of Trench 5. The colored circles represent samples for age dating. Detailed sketch of the (c) northern and (d) southern walls of Trench 5. Gray lines indicate a 1 × 1 m grid. The numbers in the yellow, red, and blue boxes represent OSL and IRSL (ka), radiocarbon (cal yr BP), and ESR (ka) dating results, respectively.

The OSL ages on the southern wall of 2010UGR-03-O and 2010UGR-04-O from unit B are 2.8 ± 0.1 and 2.6 ± 0.1 ka, respectively, and those of 2010UGR-01-O and 2010UGR-02-O from unit C are 10 ± 1 and 4.8 ± 0.2 ka, respectively (Table 1). The fault splay is cutting through unit C and failed to cut through unit B. Therefore, Trench 5 yielded a tighter MRE range of 4.8 ± 0.2–2.8 ± 0.1 ka than the MRE of Trench 4.

4.2 Paleo-stress reconstruction

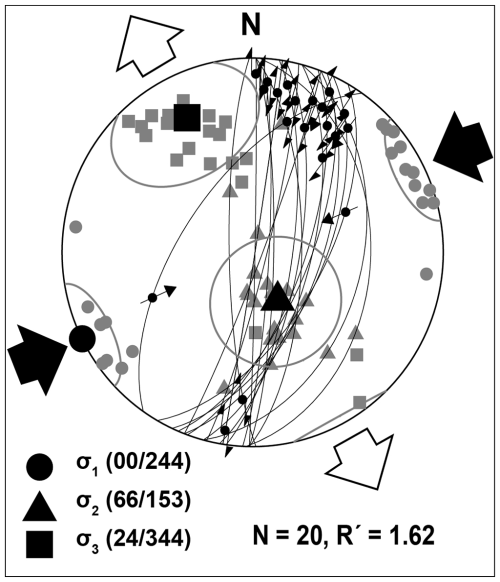

The 20 slickenlines found in the trench are divided into those in the Quaternary slip surface that cut the Quaternary sediments and those in the pre-existing fault core. For the reconstruction of the paleo-stress field, 20 kinematic data points along with the geometry of the fault planes and slickenlines were collected and analyzed using Wintensor S/W (v.5.8.5) (Delvaux and Sperner, 2003). Based on the slickenlines of the Quaternary slip surface, the analysis yielded a maximum horizontal stress (σHmax) in the ENE–WSW direction (R′ = 1.62; Delvaux et al., 1997; Fig. 8), which agrees with the current stress field on the Korean Peninsula (Park et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2016; Soh et al., 2018; Kuwahara et al., 2021). The reconstructed paleo-stress indicates that the dextral slip with a small reverse component identified in the Quaternary slip surface occurred under an ENE–WSW-oriented σHmax with vertical σ2 (strike-slip regime).

Figure 8Fault slip data in the Quaternary slip surface (lower-hemisphere, equal-area projection). Convergent and divergent arrowheads represent contraction (σHmax) and horizontal stretching (σHmin) directions, respectively. The principal stress axes σ1 (circles), σ2 (triangles), and σ3 (squares) are projected. R′ = 2−R (σ2 is vertical) [Delvaux et al., 1997; ].

4.3 Displacement and earthquake magnitude estimation

The results calculated using the marker, vertical separation of each trench, and Eq. (B1) are listed in Table 5. In a previous study by Lee et al. (2015), the horizontal displacement of the MRE at the Dangu site was determined to be 2.55 m. For each surface rupturing event in Trench 1, the horizontal displacement per event according to the event horizon is 0.9–1.05 m, and the horizontal displacement of the MRE is 1.72 m. Using the bedrock and Quaternary sediment unconformity identified by corings in Trench 2 as a marker, the cumulative horizontal displacement is 76 m. The MRE cutting the colluvial wedge in Trench 3 has a horizontal displacement of 2.85 m. However, when considering the overall interpretation, only the MRE and AE, but not the PE, are recognized in Trench 3 (Figs. 5 and 9). The displacement cutting the colluvial wedge likely reflects the displacement of the missing PE as well as the MRE, which is supported by the long interval between the wedge (unit D) and the deposit covering the wedge (unit B). Thus, it is reasonable to exclude the calculated displacement as it is unlikely to be the displacement of the MRE. The horizontal displacement of the MRE in Trench 4 and 5 is 0.82 and 2.21 m, respectively, using the lower boundary of units B and C as markers. Combining the results from each trench, the horizontal displacement of the MRE in the study area is 0.82–2.55 m and the cumulative horizontal displacement is 76 m. The horizontal displacement per event is similar, between 0.9–1.05 m for PE and AE (events 1, 2), but the trench shows a higher displacement for the MRE (event 3).

Table 5Fault displacement of the study area.

a Modified from Lee et al. (2015) b Modified from Song et al. (2020).

We estimated the maximum earthquake magnitude by applying the MD (horizontal displacement: 0.82–2.55 m) of the MRE, resulting in a maximum magnitude estimate of 6.7–7.1. Seismic SSDSs such as the 20–50 cm clastic dike and 30 cm ball-and-pillow structure observed in the exposed wall (units E and G in Trench 1; unit F in Trench 3) serve as indirect evidence indicating an earthquake of at least magnitude Mw 5.5 (Atkinson et al., 1984).

5.1 Interpretation of paleoseismic data

5.1.1 MRE and amount of surface faulting

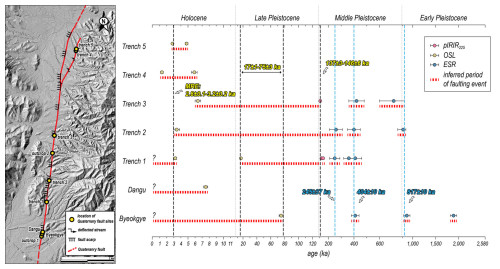

We determined the MRE and number of faulting events of the study area considering previous studies, the age of Quaternary deposits and fault gouges, the geometry and cross-cutting relationship between fault splays and sediments, and the kinematics in each trench (see Sect. 4.1). The results for each trench are synthesized to estimate the MRE, number of earthquakes (faulting events), and timing of earthquakes along the Byeokgye section (Fig. 9). First, the MRE is 3.2 ± 0.2–2.8 ± 0.1 ka, which is the time of overlap in several trenches. Considering the error range, the surface rupture must have occurred approximately 3000 years ago. Considering the minimum number of earthquakes estimated for each trench to be the maximum, at least three faulting events may have occurred along the studied section. Furthermore, the penultimate earthquake (PE) occurred at 75 ± 3–17 ± 1 ka based on the youngest age of the PE (unit C) from Trench 1 and the MRE from the Byeokgye site (Fig. 9). The antepenultimate earthquake (AE) is at 142 ± 4–137 ± 3 ka, constrained by the paleoseismic interpretation in Trench 3. On the other hand, clustering the ESR ages at each trench with an error range suggests at least three separate older earthquakes at 817 ± 10, 404 ± 10, and 245 ± 37 ka (Fig. 9). These ages indicate the time elapsed since the ESR signal is set to zero by the faulting at depth, but using this as a timing indicator of the faulting event requires care because of the possibility that the ESR signal is not completely bleached. Nevertheless, clustered faulting patterns at seven sites suggest that the study area had at least six earthquakes during the Quaternary.

5.1.2 Quaternary slip rate and recurrence interval

The slip rate is an expression of the average displacement of a fault over a certain period, which numerically shows how quickly energy (stress) accumulates in a fault zone and is used as an important input parameter in seismic hazard assessment (Liu et al., 2021). The horizontal slip rate in the study area is calculated based on the earthquake timing and horizontal displacement of each trench. We calculated slip rates from three trenches spanning different periods: Late Pleistocene to Holocene (Trench 1), Quaternary (Trench 2), and Middle Pleistocene to Holocene (Trench 3). In Trench 1, we derived a slip rate of 0.12–0.14 mm yr−1 based on the horizontal displacement of the MRE of 1.72 m and the 13.8 ± 1.2 kyr time interval between the MRE and PE (time gap between units B and C; Table 1). For Trench 2, borehole data revealed a slip rate of 0.02–0.03 mm yr−1, calculated from the cumulative horizontal displacement of 76 m and the cosmogenic 10Be–26Al isochron burial age of 2.87 ± 0.59 Ma from the lowermost Quaternary deposits. In Trench 3, we calculated a slip rate of 0.02 mm yr−1 using the 2.85 m horizontal displacement of the event that cut the colluvial wedge (unit D) and the 130.6 ± 3.4 kyr time interval between events (time gap between units B and D).

Considering the age of the deposits, the slip rate of 0.12–0.14 mm yr−1 from Trench 1 represents movement during the Holocene, while the rates from Trenches 2 and 3 may represent the cumulative slip rate (0.02 mm yr−1) throughout the Quaternary. As noted in Sect. 3.3, there are uncertainties in obtaining slip rates from 2D trenches alone on strike-slip faults such as the study area. In particular, the discontinuous distribution of Quaternary sediments may have led to a misestimation of the slip rate. There are two distinct types of sediments in the trench wall: (1) light brown sediments of Middle to Late Pleistocene age, which tend to be tilted in the vicinity of the surface rupture, and (2) dark brown, nearly horizontal Holocene sediments (Table 1, Figs. 3–7). The exact time interval between these two deposits is unknown; however, there is unconformity, and the MRE mostly cut Holocene sediments (< 10 000 years). A depositional gap, such as an unconformity, causes earthquake records to be missed during that time, leading to a misestimation of the slip rate. For this reason, in strike-slip fault settings, 3D trenching should be used because the slip rate using displacement from 2D trenches is underestimated compared to the slip rate using topography, which preserves most of the displacement. The slip rates in this study (0.12–0.14 mm yr−1) are lower compared to the slip rates derived from the topography and 3D trench reported in the study area of 0.38–0.57, 0.5 mm yr−1, respectively (Kim et al., 2024; Naik et al., 2024). Nevertheless, the slip rates in our study are meaningful as a minimum value that establishes a lower boundary for the slip rates in the study area.

The recurrence interval in the study area is also estimated. Based on the minimum of three earthquakes estimated from the number of faulting events, the interval between the MRE and PE is 14–72 kyr and between the PE and AE is 62–129 kyr (Fig. 9). The recurrence interval (RI) can be calculated using the slip rate and displacement per event (the RI is the displacement per event divided by the slip rate; Wallace, 1970). For MRE, using the slip rate (average 0.13 mm yr−1) and displacement per event (1.72 m in Trench 1), the RI is approximately 13 kyr. Using the displacement per event (average 0.98 m) and long-term slip rate (0.02 mm yr−1) for the PE and AE, the RI is roughly 49 kyr. The RI between the MRE and PE is similar to the minimum value of the time gap shown in Fig. 9 and the value estimated by the slip rate. Between the PE and AE, the recurrence interval calculated from the slip rate is smaller than the time gap obtained in Fig. 9. It suggests that the earthquake records in the trench are not complete. Therefore, we can make a conservative estimate that the recurrence interval of the study area is over 13 000 years. Although no clear recurrence interval has been presented in Korean paleoseismic studies, Kim and Lee (2023) used ESR ages to suggest that the Yangsan Fault follows a quasi-periodic model and has a recurrence interval of approximately 100 kyr, which is closely related to the interval of interglacial sea level loading over the Late Quaternary. However, the recurrence interval may be shorter if the complexity of the fault distribution is combined with external factors, such as increased seismicity on the Korean Peninsula after the Tohoku Earthquake (Hong et al., 2015, 2018) or changes in slip rates.

5.2 Structural patterns of Quaternary reactivation of the Yangsan Fault

The trenches revealed the following common features. First, the hanging wall of the Quaternary slip surface is mostly deposited with Holocene sediments only, with no Middle Pleistocene sediments present. This indicates that reverse faulting has occurred continuously since at least the Middle Pleistocene. Second, NNE- to N–S-striking Quaternary slip surfaces with high-angle dip have rakes of 20° or less, indicating dextral slip with a minor reverse component. Third, the main surface rupture has a top-to-the-west geometry, and its hanging wall consists of a pre-existing fault core in all trenches. Fieldwork and previous studies revealed that the A-type alkaline granite in the study area is a dextral offset marker of the Yangsan Fault (Hwang et al., 2004, 2007a, b), and a vertically drilled borehole from the footwall of Trench 2 revealed that the basement rock is A-type alkali granite. In addition, Kim et al. (2022) conducted inclined borehole drilling and microstructural studies in the vicinity of Trench 1 and identified a fault damage zone, undeformed wall rock, and fault core approximately 25 m wide on the eastern side of the A-type alkali granite. Multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that the pre-existing fault core distributed on the trenches is the main fault core zone of the Yangsan Fault cutting the A-type alkali granite and that the western boundary of the main fault core was reactivated during the Quaternary. The slip surface where the A-type alkali granite contacts the main fault core suggests that it was in a more slip-prone state (e.g., low coefficient of friction, foliated smectite-rich slip zone; Woo et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2022) during the Quaternary than other slip surfaces within the fault core. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the western boundary of the fault core within the Yangsan Fault zone has been reactivated as a dextral slip with a small reverse component since at least the Early Pleistocene, causing surface rupture in the study area.

A Quaternary surface rupture with a top-to-the-west geometry and a hanging wall composed of fault core is characterized not only in the study area but also throughout the Yangsan Fault. All Quaternary fault sites on the Yangsan Fault, except for the Bogyeongsa site (top to the east; BGS in Fig. 10; Lee et al., 2022), show the top-to-the-west geometry of the main surface rupture (Kyung, 2003; Choi et al., 2012; Cheon et al., 2020a; Han et al., 2021; Ko et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2023). At the Quaternary fault sites north of the study area, pre-existing fault cores are observed on the hanging wall of the main slip surface (Kyung, 2003; Choi et al., 2012; Han et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2022; Ko et al., 2022; Lee, 2023). The deformation pattern of the Quaternary faulting of the Yangsan Fault is top to the west, with the main fault core and unconsolidated sedimentary layers abutting the main surface rupture.

Figure 10MRE of Yangsan Fault. Green stars indicate where MREs have been identified due to the presence of Quaternary sediment ages. GS: Gasan (Lim et al., 2021), IB: Inbo (Cheon et al., 2020a), IBN: Inbo north, MH: Miho, WS: Wolsan (Kim et al., 2023), BG: Bangok (Lee, 2023), YG: Yugye (Kyung, 2003), BGS: Bogyeongsa (Lee et al., 2022), GOS: Goesi (Ko et al., 2022), PH: Pyoenghae (Choi et al., 2012), OG: Ogok (Han et al., 2021). “No obvious proof” refers to areas where sites that cut unconsolidated sediments are present but not dated.

5.3 MRE and activity for each segment of the Yangsan Fault

The MRE of the Yangsan Fault is analyzed section by section by synthesizing previous studies (Fig. 10). The Bangok (BG) and Yugye (YG) sites adjacent to the north of the study area have similar MREs. The Bangok site, which is closest to the study area, shares the same MRE, after 3000 years ago (Lee, 2023), while the Yugye site has the youngest MRE along the entire Yangsan Fault, after 646 CE (Kyung, 2003). It is clear that the section from the study area to the Yugye site, including the Bangok site, is the most recently ruptured section of the Yangsan Fault, with the last surface rupture occurring at approximately < 3.0 ka (red arrow in Fig. 10). The Bogyeongsa (BGS) site, north of the Yugye site, has an MRE of Middle Pleistocene and Holocene age (Lee et al., 2022). The Yeongdeok area, which extends from the northern part of the Bogyeongsa site to the Goesi (GOS) site, has several reported Quaternary fault sites, though no conclusive evidence of Quaternary faulting exists. This is due to either the cutting of unconsolidated sediments without age constraint or the lack of displacement of unconsolidated sediments, with only ESR ages available for the fault gouge (Choi et al., 2012). The MREs at the Ogok (OG), Pyeonghae (PH), and Goesi sites in the northernmost region of the northern Yangsan Fault date to both the Late Pleistocene and Holocene (Choi et al., 2012; Han et al., 2021; Ko et al., 2022). Overall, the northern part of the Bogyeongsa site (the northern part of the northern Yangsan Fault) experienced MREs between the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene. The Angang area beyond the south of the study area has no reports of Quaternary faulting, and at the Wolsan (WS) site, in the northernmost part of the southern Yangsan Fault, the MRE is Late Pleistocene. The Miho (MH), Inbo north (IBN), and Inbo (IB) sites of the southern Yangsan Fault are all Late Pleistocene in age, and the southernmost part of the Yangsan Fault, the Gasan (GS) site, is after the Late Pleistocene (Lim et al., 2021). The southern Yangsan Fault from the Wolsan site to the Gasan site experienced MREs mostly in the Late Pliocene. At first glance, it may appear that the section between Yugye and the study area is more active with Holocene MREs, but the timing of the MREs alone is inadequate to assess which zone is more active. For example, a Holocene surface rupture may indicate that the fault has a short recurrence interval; conversely, a fault with an older MRE may have higher potential for future earthquakes because recent faulting events may have released stress accumulation. Deviation in the timing of MREs at different sites or sections can be a direct indication of the fault motion that caused the surface rupture; however, uncertainty in age constraints due to the presence or absence of sediments must be considered. The MRE is an important factor in activity assessment because if it has a recurrence interval, the elapsed time can be calculated, which can be used to predict future earthquakes. However, the activity considered using MRE alone can be misleading; therefore, it is necessary to derive recurrence intervals and elapsed time to accurately predict earthquakes based on paleoseismic data. Ultimately, activity assessment should consider not only paleoseismic data but also topographic, structural, seismic, and geodetic aspects.

We conducted surface geological surveys, trenching, coring, OSL–IRSL dating, radiocarbon dating, ESR dating, and cosmogenic nuclide dating along the lineament extracted from topographic analysis using high-resolution lidar imagery at the Yangsan Fault. The primary aim is to identify the surface ruptures that occurred during the Quaternary period, derive structural features, and gather paleoseismic data for the Quaternary surface rupture. The main conclusions are as follows.

(1) A comprehensive analysis, combining two previously reported Quaternary fault sites (Byeokgye and Dangu), two newly discovered natural outcrop sites, five trenches, coring surveys, and dating of unconsolidated sediments, charcoal, and fault rocks, revealed a 7.6 km Quaternary surface rupture along the Yangsan Fault. (2) The Quaternary surface ruptures in the study area exhibited an east-dipping geometry with a N–S to NNE strike and moved as a dextral slip with a reverse slip component during the Quaternary. (3) At least six faulting events are interpreted from the trench walls, with an MRE approximately 3000 years ago. The MRE horizontal displacement ranged from 0.82 to 2.55 m, cumulative horizontal displacement is 76 m, horizontal displacement per event before the MRE ranged from 0.9 to 1.05 m, and maximum magnitude using the MD is Mw 6.7–7.1. The slip rate is 0.12–0.14 mm yr−1, with a recurrence interval of at least 13 000 years. (4) The Quaternary structural features indicate that during the Quaternary period, the western boundary of the main fault core of the Yangsan Fault was reactivated under ENE–WSW compressional stress. The top-to-west geometry is consistent with that observed throughout the Yangsan Fault. (5) The southern part of the northern Yangsan Fault, including the study area, documents a Holocene MRE that is younger than those documented in the southern Yangsan Fault.

Surface rupturing has been observed along most sections of the Yangsan Fault and in the study area, and basic paleoseismic studies continue to be reported (Fig. 10; Lee et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2023). The challenge is that Korea's geologic diversity results in a large number of faults that need to be studied (e.g., Chugaryeong Fault). Only then will it be possible to properly understand the seismicity pattern of Korea and the earthquakes in the low-activity intraplate regions. Although the study results are only for a small 10 km section of the Yangsan Fault with a 200 km extension, the San Andreas Fault, which has high-resolution paleoseismic data from more than 200 trenches, also started out in the same way. In particular, studying seismic hazards on the Korean Peninsula, with its urbanization, cultivated land, slow slip rates, long recurrence intervals, and fast erosion rates, is a challenge. This research will hopefully contribute to the research on earthquake hazards in Korea, which is just beginning to advance. Furthermore, this study contributes valuable insights for seismic hazard assessment in the region and offers a broader understanding of intraplate earthquake dynamics, thereby aiding earthquake prediction efforts.

The topography of the study area in Ha et al. (2022) is summarized as follows.

The study area's topography is divided into a lowland area to the west and a mountainous region to the east (Fig. A1). In the eastern mountains, the ridges extending from the summit are cut off by a lineament heading west, which influences the drainage system, with streams flowing from the high elevations east to west. Alluvial fans, formed from sediments from the eastern mountains, are found at the base of the slopes. A total of 12 lineaments are identified, with the main lineament, which extends for 7.6 km, displaying high activity through the northern part of the Byeokgye site. Subsidiary high-activity lineaments and low-activity lineaments, mainly following N–S or NNE directions, are present, though many are valleys formed by erosion rather than rupturing. The main lineament exhibits continuous fault scarps and deflected streams, with reservoirs often located along it due to impermeable fault gouges that enable water storage. Topographic analysis revealed fault scarps, knickpoints, and displacement features along the main lineament, particularly visible in lidar data. Fault scarps are continuously and distinctly visible in the main lineament of the southern region (Fig. A2). In the cross-section, the fault scarps are recognized as knickpoints, and on the topographical map, the ridges on the east side of the lineament are cut by the surface rupture and merged with the alluvial fans. The main lineament of the northern region is identified as a linear arrangement of deflected streams and fault scarps (Fig. A3). Unlike in the south, the fault scarps in the north show surface uplift estimated at a vertical offset of between 2–4.2 m of the same alluvial fan surface cross-section. Differences between the southern and northern regions are observed, with the north showing vertical offsets of 2–4.2 m and more pronounced faulting. The horizontal offsets calculated based on the three deflected streams are 92, 98, and 150 m. The tendency for the offset to decrease as the distance from the main lineament increases indicates that the fault offset branching from the main surface rupture gradually decreases.

Figure A2(a) A detailed topographic map of the southern region. (b) Topographic profiles along the main lineament (blue line in a) crossing the fault scarps. Black arrows mark knickpoints identified as fault scarps. (c) A 3D hillshade image. The red arrows highlight the fault scarp, which is clearly visible to the unaided eye (modified from Ha et al., 2022).

Figure A3(a) A detailed topographic map of the northern region. An NNE lineament branching off from the main lineament is shown by the dextrally deflected stream. (b) Topographic profiles along the line (blue line in a) crossing the fault scarps. Fault scarps in the northern region are evident due to the elevation difference in the alluvial fan surfaces. (c) A 3D hillshade image. Red arrows highlight the fault scarp (modified from Ha et al., 2022).

Figure B1(a) Schematic diagram showing how to calculate true displacement. Sh: horizontal displacement St: true displacement, Sv: vertical displacement, Sm: dip separation, α: dip of fault surface, β: dip of cut slope, γ: rake of the striation (modified from Xu et al., 2009). (b, c) Photographs showing the measured vertical separation of Trenches 1 and 5. Svm: vertical separation.

The horizontal displacement (Sh) can be calculated using a trigonometric function that considers the vertical displacement (Sv), fault dip angle (α), rake (γ), true displacement (St), and their relationships (Fig. B1; Eq. B1). Assume that the attitude of the marker in the exposed wall at each trench is nearly horizontal in three dimensions and the angle (β) of the exposed wall is nearly vertical; then the two factors are perfectly horizontal and vertical, respectively. Thus, the vertical separation (Svm) and vertical displacement (Sv) measured in the exposed wall are equal.

Therefore,

We calculate horizontal displacement (Sh) using Eq. (B1) for vertical separation (Svm) of the marker measured in the exposed wall, as shown in Table 5.

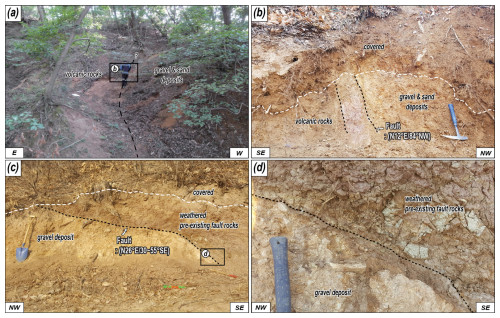

Outcrop 1 is located 30 m south of the Byeokgye site (Fig. 2c). A high-angle rupture cuts the Cretaceous volcanic rocks and unconsolidated sediments interbedded with gravel deposits and sand layers (Fig. C1a). The rupture trace is partially recognized on the surface based on the lithological distribution. The fault core consists of a 20 cm wide breccia with a Quaternary slip surface attitude of N12° E, 84° NW, and no clear slickening is observed (Fig. C1b). Outcrop 2, on the extension of the main lineament, is located 2.7 km north of the Byeokgye site (Fig. 2c). The outcrop contains highly weathered purple sedimentary rock overlying unconsolidated sediments (Fig. C1c). The NNE-striking fault splay dips toward the east with a low angle. The purple sedimentary rock of the hanging wall is mostly clayey and may be either a pre-existing purple fault gouge or weathered purple Cretaceous sedimentary rock. The fault core adjacent to the unconsolidated deposits consists of a 2–3 cm thick foliated fault gouge (Fig. C1d). The foliation is subparallel to the slip surface. The unconsolidated gravel deposits have poor sorting, and angular clasts consist of sandstone, granitic, and volcanic rocks. No clear slickenlines are observed owing to highly weathered outcrop conditions. We could not date either outcrop because the clast-rich sediments are not suitable for OSL dating and did not include organic material for 14C dating.

Figure C1Photographs showing the outcrops of the rupture that cuts the unconsolidated sediments. (a) Rupture trace on the surface. (b) A NNE-striking rupture cuts the boundary between volcanic rocks and gravel and sand deposits. The fault rock is composed of breccia. (c) Weathered pre-existing fault rocks thrust gravel deposits along the low-angle surface rupturing. (d) Close-up photograph of the rupture. A 2–3 cm thick fault gouge forms a boundary between two different rocks.

We cored the footwall of Trench 2. Unconsolidated sand and gravel deposits alternate up to 24 m below the surface. From 24 to 32.8 m, the material consists of a granite wash, at the base of which a 1.2 m thick weathering zone is recognized. From 34 m onwards, the bedrock is clearly identified as A-type alkaline granite (Fig. D1). We performed 10Be–26Al isochron burial dating on the granite wash immediately above the basement rock.

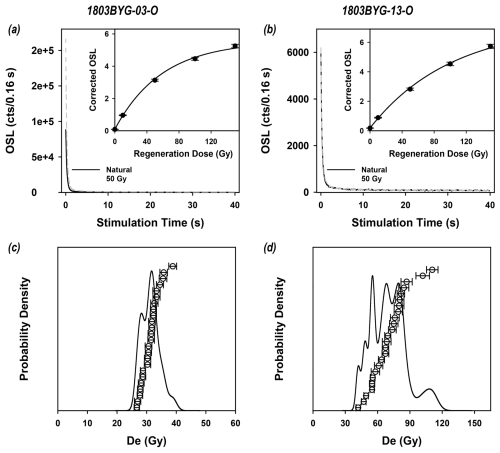

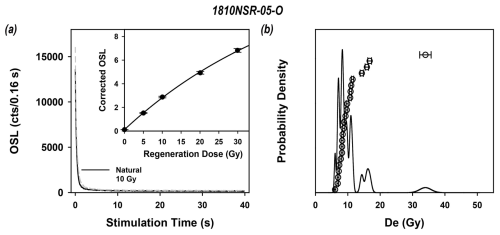

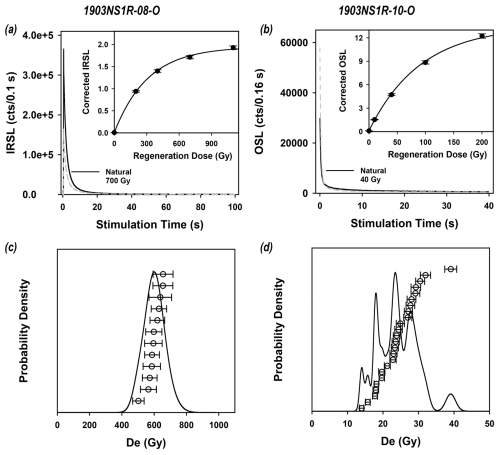

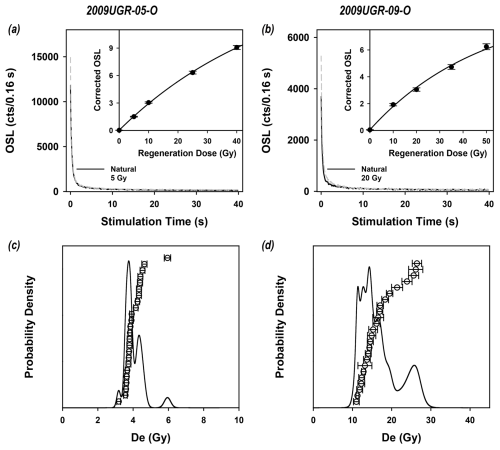

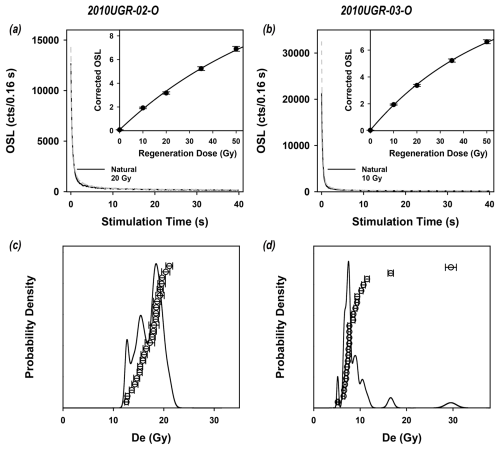

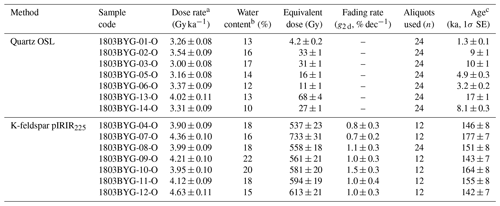

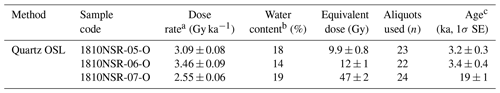

Graphs show the detailed results for one to two representative samples per trench for quartz OSL and pIRIR255. We selected samples from sediments cut into the MRE and from sediments overlying the MRE. The graphs include decay curves, probability density graphs, and 10Be–26Al isochron graphs. The tables also include dose rates, equivalent doses, and luminescence ages of the samples from each trench.

Figure E1Representative quartz OSL decay curves (a, b) and probability density graph (c, d) of Trench 1.

Figure E2Representative quartz OSL decay curves (a, b) and probability density graph (c, d) of Trench 2.

Figure E3Representative quartz OSL–IRSL decay curves (a, b) and probability density graph (c, d) of Trench 3.

Figure E4Representative quartz OSL decay curves (a, b) and probability density graph (c, d) of Trench 4.

Figure E5Representative quartz OSL decay curves (a, b) and probability density graph (c, d) of Trench 5.

Table E1Dose rates, equivalent doses, and luminescence ages of the samples from Trench 1.

a Wet total dose rates. The activities of each radionuclide were converted to dose rates using the data presented by Liritzis et al. (2013). Cosmic ray dose rates were estimated using the method suggested by Prescott and Hutton (1994). The internal dose rate of K-feldspar was calculated assuming internal K content of 12.5 % and by using the methods proposed by Mejdahl (1987) and Readhead (2002). For deriving the total dose rates absorbed by K-feldspar, the internal dose rate of 0.736 ± 0.04 Gy ka−1 was added to the external ones of each sample. b Present water content. c Fading-corrected ages in the case of K-feldspar.

Table E2Dose rates, equivalent doses, and luminescence ages of the samples from Trench 2.

a Wet total dose rates. The activities of each radionuclide were converted to dose rates using the data presented by Liritzis et al. (2013). Cosmic ray dose rates were estimated using the method suggested by Prescott and Hutton (1994). b Present water content.

Table E3Dose rates, equivalent doses, and luminescence ages of the samples from Trench 3.

a Wet total dose rates. The activities of each radionuclide were converted to dose rates using the data presented by Liritzis et al. (2013). Cosmic ray dose rates were estimated using the method suggested by Prescott and Hutton (1994). The internal dose rate of K-feldspar was calculated assuming internal K content of 12.5 % and by using the methods proposed by Mejdahl (1987) and Readhead (2002). For deriving the total dose rates absorbed by K-feldspar, the internal dose rate of 0.736 ± 0.04 Gy ka−1 was added to the external ones of each sample. b Present water content. c Fading-corrected ages in the case of K-feldspar

Table E4Dose rates, equivalent doses, and luminescence ages of the samples from Trench 4.

a Wet total dose rates. The activities of each radionuclide were converted to dose rates using the data presented by Liritzis et al. (2013). Cosmic ray dose rates were estimated using the method suggested by Prescott and Hutton (1994). b Present water content.

Table E5Dose rates, equivalent doses, and luminescence ages of the samples from Trench 5.

a Wet total dose rates. The activities of each radionuclide were converted to dose rates using the data presented by Liritzis et al. (2013). Cosmic ray dose rates were estimated using the method suggested by Prescott and Hutton (1994). b Present water content.

Questions or requests regarding the research data in this article can be sent to the corresponding author.

Conceptualization: SH, HCK. Funding acquisition: SM. Investigation: SM, HCK, SL, YBS, JHC, SJK. Project administration: SM. Supervision: SM. Validation: YBS, JGC, SJK. Visualization: SM, SJK. Writing (original draft preparation): SH. Writing (review and editing): SH, YBS, JHC, SM.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We appreciate two anonymous referees and the editor for their constructive comments that helped improve the article.

This research was supported by a grant (grant no. 2022-MOIS62-00, RS-2022-ND640011) from National Disaster Risk Analysis and Management Technology in Earthquakes funded by the Ministry of Interior and Safety (MOIS, Korea) and supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (grant no. NRF-2023S1A5B5A16080131).

This paper was edited by Yang Chu and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ansari, K. and Bae, T. S.: Contemporary deformation and strain analysis in South Korea based on long-term (2000–2018) GNSS measurements, Int. J. Earth Sci., 109, 391–405, https://doi-org-ssl.oca.korea.ac.kr/10.1007/s00531-019-01809-4, 2020.

Argus, D. F., Gordon, R. G., Heflin, M. B., Ma, C., Eanes, R. J., Willis, P., Peltier, W. R., and Owen, S. E.: The angular velocities of the plates and the velocity of the Earth's centre from space geodesy, Geophys. J. Int., 18, 1–48, https://https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04463.x, 2010.

Ashurkov, S. V., San'kov, V. A., Miroschnichenko, A. I., Lukhnev, A. V., Sorokin, A. P., Serov, M. A., and Byzov, L. M.: GPS geodetic constrains on the kinematics of the Amurian Plate, Russ. Geol. Geophys+., 52, 239–249, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rgg.2010.12.017, 2011.

Atkinson, G. M., Finn, W. D. L., and Charlwood, R. G.: Simple computation of liquefaction probability for seismic hazard applications, Earthq. Spectra, 1, 107–123, https://doi.org/10.1193/1.1585259, 1984.

Balco, G. and Rovey, C. W.: An isochron method for cosmogenic-nuclide dating of buried soils and sediments, Am. J. Sci., 308, 1083–1114, https://doi.org/10.2475/1 0.2008.02, 2008.

Bird, P.: An updated digital model of plate boundaries, Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 4, 1027, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GC000252, 2003.

Bonilla, M. G., Mark, R. K., and Lienkaemper, J. J.: Statistical relations among earthquake magnitude, surface rupture length, and surface fault displacement, B. Seismol. Soc. Am., 74, 2379–2411, https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/ssa/bssa/article/74/6/2379/118679/Statistical-relations-among-earthquake-magnitude (last access: 6 February 2025), 1984.

Bronk Ramsey, C.: Methods for summarizing radiocarbon datasets, Radiocarbon, 59, 1809–1833, https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2017.108, 2017.

Buylaert, J. P., Murray, A. S., Thomsen, K. J., and Jain, M.: Testing the potential of an elevated temperature IRSL signal from K-feldspar, Radiat. Meas., 44, 560–565, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radmeas.2009.02.007, 2009.

Buylaert, J. P., Jain, M., Murray, A. S., Thomsen, K. J., Thiel, C., and Sohbati, R.: A robust feldspar luminescence dating method for Middle and Late Pleistocene sediments, Boreas, 41, 435–451, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3885.2012.00248.x, 2012.

Calais, E., Dong, L., Wang, M., Shen, Z., and Vergnolle, M.: Continental deformation in Asia from a combined GPS solution, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L24319, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL028433, 2006.