the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Distribution, microphysical properties, and tectonic controls of deformation bands in the Miocene subduction wedge (Whakataki Formation) of the Hikurangi subduction zone

Kathryn E. Elphick

Craig R. Sloss

Klaus Regenauer-Lieb

Christoph E. Schrank

We analyse deformation bands related to horizontal contraction with an intermittent period of horizontal extension in Miocene turbidites of the Whakataki Formation south of Castlepoint, Wairarapa, North Island, New Zealand. In the Whakataki Formation, three sets of cataclastic deformation bands are identified: (1) normal-sense compactional shear bands (CSBs), (2) reverse-sense CSBs, and (3) reverse-sense shear-enhanced compaction bands (SECBs). During extension, CSBs are associated with normal faults. When propagating through clay-rich interbeds, extensional bands are characterised by clay smear and grain size reduction. During contraction, sandstone-dominated sequences host SECBs, and rare CSBs, that are generally distributed in pervasive patterns. A quantitative spacing analysis shows that most outcrops are characterised by mixed spatial distributions of deformation bands, interpreted as a consequence of overprint due to progressive deformation or distinct multiple generations of deformation bands from different deformation phases. As many deformation bands are parallel to adjacent juvenile normal faults and reverse faults, bands are likely precursors to faults. With progressive deformation, the linkage of distributed deformation bands across sedimentary beds occurs to form through-going faults. During this process, bands associated with the wall-, tip-, and interaction-damage zones overprint earlier distributions resulting in complex spatial patterns. Regularly spaced bands are pervasively distributed when far away from faults. Microstructural analysis shows that all deformation bands form by inelastic pore collapse and grain crushing with an absolute reduction in porosity relative to the host rock between 5 % and 14 %. Hence, deformation bands likely act as fluid flow barriers. Faults and their associated damage zones exhibit a spacing of 9 m on the scale of 10 km and are more commonly observed in areas characterised by higher mudstone-to-sandstone ratios. As a result, extensive clay smear is common in these faults, enhancing the sealing capacity of faults. Therefore, the formation of deformation bands and faults leads to progressive flow compartmentalisation from the scale of 9 m down to about 10 cm – the typical spacing of distributed, regularly spaced deformation bands.

- Article

(38315 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1305 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

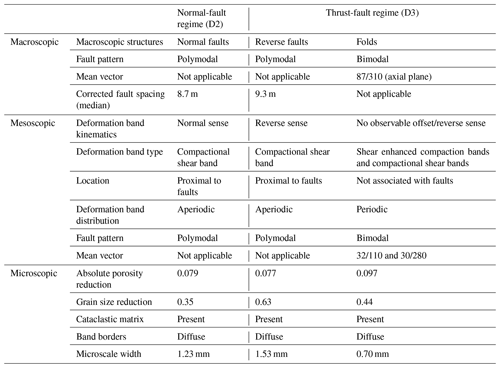

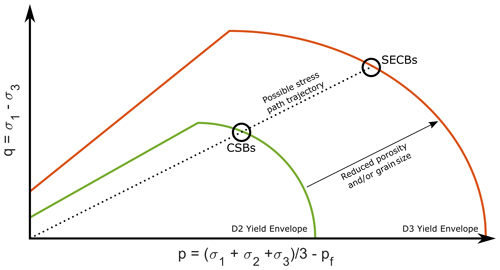

Deformation bands (DBs) are defined as tabular, oblate zones of localised plastic shear and volume change produced through inelastic yielding in granular material (porosity > 5 %) (Aydin, 1977, 1978; Aydin and Johnson, 1983; Okubo and Schultz, 2005; Schultz and Siddharthan, 2005). Bands often exhibit millimetre- to centimetre-scale offset and most commonly have lengths > 100 m, but they do not act as planes of significant displacement discontinuity, which distinguishes them from faults (Aydin, 1977; Antonellini et al., 1994; Świerczewska and Tokarski, 1998; Aydin et al., 2006; Fossen et al., 2007). DBs are characterised by small displacement-to-thickness ratios and are thicker than faults of comparable length (Fossen et al., 2007). Kinematic classification recognises five types of deformation band: pure compaction bands, compactional shear bands, isochoric shear bands, dilatant shear bands, and pure dilation bands (Fossen et al., 2007; Eichhubl et al., 2010). The kinematics are commonly linked to stress state through the cam-cap model of yielding and band formation (Fig. 1) (Wong et al., 1992; Schultz and Siddharthan, 2005; Fossen et al., 2007). In this approach, the yield envelope of porous granular media is represented by a non-linear surface in Q–P space within which Q and P signify differential stress and effective mean stress respectively:

where σ1, σ2, and σ3 denote the principal stresses of the Cauchy stress tensor, and Pf is pore-fluid pressure. The cam-cap yield surface links the state of stress at the time of deformation localisation to the kinematics and orientation of DBs. Current literature hypothesises that the point of intersection, and therefore the orientation and band kinematics, is controlled by the tectonic regime (Soliva et al., 2013; Ballas et al., 2014; Soliva et al., 2016; Fossen et al., 2018). During horizontal extension, higher Q and lower P are predicted, resulting in DBs characterised by a high shear component that are oblique (ca. 30–50∘) to the maximum principal compressive stress (Ballas et al., 2013; Soliva et al., 2013; Ballas et al., 2014; Soliva et al., 2016). In contrast, during horizontal contraction, higher P is predicted. This results in DBs characterised by low shear-to-compaction ratios that are perpendicular to sub-perpendicular to the maximum principal compressive stress (Ballas et al., 2013; Soliva et al., 2013; Ballas et al., 2014; Soliva et al., 2016).

Figure 1Cam-cap yield envelope showing the relationship between the stress state at the point of inelastic yielding and the type and orientation of the deformation band that nucleates. In horizontal contraction, higher effective mean stresses are predicted, resulting in the formation of bands characterised by low shear-to-compaction ratios. Comparatively, during horizontal extension, higher differential stresses are predicted, resulting in bands characterised by high shear-to-compaction ratios. The yield envelope shrinks with increased porosity and/or grain size of the material. Adapted from Fossen et al. (2007).

DBs can also be classified by the deformation mechanism that was active during their formation. The dominant deformation mechanisms observed in deformation bands are granular flow, cataclasis, phyllosilicate smearing, and dissolution and cementation (see Fossen et al., 2007, for a review). The deformation mechanism depends on the grain size, sorting, mineralogy, diagenetic history, porosity, and stress state (Fossen et al., 2007) and controls petrophysical properties (Fossen and Bale, 2007; Ballas et al., 2015; Fossen et al., 2018). In nature, shear bands with associated compaction are most commonly observed, formed by grain rearrangement and porosity collapse with or without cataclasis (Fossen et al., 2007). Cataclasis is often the dominant deformation mechanism in bands formed at > 1 km depth. Disaggregation bands form via granular flow and are dominant at shallower levels (Fossen et al., 2007). Additionally, if the host rock contains > 10 % platy minerals, phyllosilicate bands, characterised by fine-grained, low-porosity zones containing aligned phyllosilicates can form (Knipe et al., 1997; Fossen et al., 2007). In these bands, platy minerals promote frictional grain boundary sliding and inhibit grain fracturing (Fossen et al., 2007). In clay-rich rocks (> 40 %), deformation can produce clay smears with very low permeability that commonly accumulate greater offsets than other types of bands (Antonellini et al., 1994; Fisher and Knipe, 2001; Fossen et al., 2007).

Besides its relevance for understanding strain localisation in rocks, the study of DBs is important because of their sealing potential and effect on fluid flow in hydrocarbon and groundwater reservoirs (Antonellini and Aydin, 1994; Ogilvie and Glover, 2001; Fossen and Bale, 2007; Fossen et al., 2007; Ballas et al., 2013, 2015; Qu et al., 2017; Fossen et al., 2018). DBs commonly exhibit a reduction in permeability compared with the host rock, subsequently acting as barriers to fluid flow (Ogilvie et al., 2001; Ogilvie and Glover, 2001; Fossen and Bale, 2007; Fossen et al., 2007; Balsamo et al., 2012; Ballas et al., 2015; Fossen et al., 2018). The relative proportion of clay incorporation and cataclasis controls the petrophysical properties of the bands. Bands characterised by greater concentrations of clay and greater degrees of cataclasis are more effective barriers (Fossen et al., 2007; Ballas et al., 2015; Fossen et al., 2018). The extent to which DBs can impact reservoir fluid flow depends not only on their petrophysical properties but also on their spatial distribution (Ogilvie and Glover, 2001; Sternlof et al., 2006; Fossen and Bale, 2007; Torabi et al., 2013; Ballas et al., 2015). In nature, deformation bands exhibit two spatial distributions: networks of bands concentrated into clusters or zones in the vicinity of faults (Antonellini and Aydin, 1995; Shipton and Cowie, 2001, 2003; Soliva et al., 2013; Ballas et al., 2014), and a pervasive periodic and/or clustered distribution across a deformed region, unrelated directly to faults (Saillet and Wibberley, 2010; Ballas et al., 2013; Soliva et al., 2013, 2016). Field studies suggest that the spatial distribution of deformation bands is largely controlled by the tectonic regime in which they form (Saillet and Wibberley, 2010; Solum et al., 2010; Soliva et al., 2013; Ballas et al., 2014; Soliva et al., 2016). Deformation bands associated with an extensional regime are observed in the damage zone of faults where the band density increases as the fault plane is approached (Shipton and Cowie, 2003; Schueller et al., 2013; Pizzati et al., 2020). Conversely, deformation bands formed during horizontal contraction exhibit distributed, regular spacing (Ballas et al., 2013; Soliva et al., 2013; Fossen et al., 2015). However, the control of tectonic regime has only be tested in one field site (Provence, France) where the host rock, comprising mainly quartz-rich deltaic sandstone characterised by large heterogeneities in terms of grain size and porosity, contains bands formed in horizontal extension and horizontal contraction (Saillet and Wibberley, 2010; Ballas et al., 2013; Soliva et al., 2013; Ballas et al., 2014; Soliva et al., 2016). Thus, other field studies are required to potentially falsify the notion of the control of tectonic regime.

Here, we analyse faults and deformation bands formed in poly-deformed Miocene siliciclastic turbidites of the exposed Hikurangi subduction wedge in the eastern North Island of New Zealand to test if the influence of tectonic regime documented in previous studies applies. The studied rock package has been deformed in both horizontal extension and horizontal contraction, with strike-slip reactivation of some extensional faults. The host rock comprises interbedded sandstones, siltstones, and mudstones of the Whakataki Formation (Lee and Begg, 2002). Previous studies on the relationship between deformation band distribution and the tectonic setting analysed deformation bands hosted within mineralogically relatively homogeneous sandstones in two key locations: (1) Utah, USA, where the deformation bands are associated with the intracontinental Laramide orogeny (Aydin, 1978; Antonellini et al., 1994; Solum et al., 2010; Fossen et al., 2011), and (2) Provence, France, where bands formed during the Cretaceous Pyrenean intracontinental mountain building event and the subsequent Oligocene–Miocene rifting (Saillet and Wibberley, 2010; Ballas et al., 2013; Soliva et al., 2013; Ballas et al., 2014; Soliva et al., 2016). In addition, band kinematics and orientations have been studied in DBs that are hosted in the Nubian Sandstone, western Sinai, Egypt, that formed during Oligocene–Miocene rifting associated with the separation of the African and Arabian plates (e.g. Rotevatn et al., 2008; Tueckmantel et al., 2010) and in poorly lithified sandstones observed in the Crotone Basin, southern Italy, that formed in association with extensional tectonics related to back-arc extension (Balsamo and Storti, 2011; Balsamo et al., 2012; Pizzati et al., 2020). In Utah, Provence, and western Sinai, the host rocks mainly consist of quartz. The DBs exhibit porosity reduction and grain size reduction due to cataclasis compared with the host rock. The magnitude of porosity and grain size reduction depend on the burial depth at the time of deformation. The host rocks in southern Italy are less mature with a greater proportion of feldspar. In these rocks, deformation of fault rock is accommodated through a combination of cataclasis and grain-scale mixing (Balsamo and Storti, 2011). The units studied in this research are compositionally less mature than the host rocks of the previous study sites. With greater clay content and more lithological heterogeneity, different deformation mechanisms are expected (Fossen et al., 2007).

DBs hosted within units that are characterised by greater lithological heterogeneity and higher clay content have been studied primarily through core data collected from the North Sea (Knipe et al., 1997; Fisher and Knipe, 1998; Knipe et al., 1998; Fossen and Hesthammer, 2000; Fisher and Knipe, 2001; Farrell et al., 2014). In these bands, extensive grain-scale mixing of sand and clay is observed (Fisher and Knipe, 2001; Kristensen et al., 2013). Some clay layers form clay smears that maintain integrity for distances several times that of the layer thickness (Kristensen et al., 2013). Deformation bands deformed at <1.4 km depths exhibit grain size reduction by cataclasis in addition to grain-scale mixing, consistent with previous studies showing increased cataclasis at > 1 km depth (Antonellini et al., 1994). However, bands deformed at depths below ca. 1.5 km in mixed sequences have not been described in detail. Deformation bands formed in impure sandstones (15 %–40 % clay) at > 3 km depth within the Rotliegend reservoir are uncommon and are thus not discussed (Fisher and Knipe, 2001). Therefore, a comprehensive description of the orientation, kinematics, and spatial distribution of deformation bands hosted in mixed sequences and deformed at > 1.5 km depth is presently missing from the literature and is addressed in this research. Furthermore, the Whakataki Formation has been deformed in a subduction wedge (Cape et al., 1990; Chanier and Ferrière, 1991; Rait et al., 1991; Chanier et al., 1999; Nicol et al., 2007; Bailleul et al., 2013). While this tectonic setting attracts significant research attention because of its association with megathrust earthquakes and hydrocarbon reservoirs, studies of deformation bands within these settings are limited due to complex structural overprints by later-stage deformation structures. The studies that have analysed deformation bands in an active accretionary prism (Lucas and Moore, 1986; Karig and Lundberg, 1990; Labaume et al., 1997; Maltman, 1998; Ujiie et al., 2004) have not done so with the primary goal of testing how the tectonic setting and stress state influences the kinematics and distribution of bands. Bands in accretionary prisms are mainly observed in the toe of the prism, are associated with shallow (<500 m) deformation, and are only observed in silts or clays. Through continual accretion and internal deformation, many rock packages travel deep into the prism reaching burial depths of > 5 km. This causes overprint of structures that form in the upper few kilometres of the wedges, thereby limiting our understanding of shallow deformation processes (e.g. Maltman, 1998). The Whakataki Formation travelled along a shallow trajectory through the Hikurangi subduction wedge, with a maximum burial depth of 3–4 km (Wells, 1989). Analysis of the structures within the Whakataki Formation can improve our understanding of how siliciclastic rocks accommodate deformation in the shallow regions of subduction wedges. Moreover, the chosen field site offers the opportunity to study deformation bands hosted in a mixed clay-sand sequence that have formed under horizontal contraction. Finally, the Whakataki Formation has been buried to depths within the hydrocarbon formation window (2–3 km) (e.g. Bustin, 1991) and overlies potential source rocks of the underlying Waipawa Formation, thereby making the unit a potential reservoir (Leckie et al., 1994; Field et al., 2006). Previous studies have analysed rocks buried to <2 km depth. For example, the sandstones of the Provence study site were buried to 0.4–0.6 km (Soliva et al., 2013) whereas those in Utah, western Sinai, and southern Italy were buried to 1–2 km (Du Bernard et al., 2002; Rotevatn et al., 2008; Balsamo and Storti, 2010, 2011; Fossen et al., 2011; Balsamo et al., 2012). As DBs are commonly associated with a reduction in permeability and porosity (Fossen and Bale, 2007), it is useful to study their spatial distribution and microphysical properties in potential hydrocarbon reservoir rocks (Field et al., 2006) that travelled through the hydrocarbon window. Preliminary offshore drilling of the Miocene siliciclastic rocks has documented significant gas shows (Amoco New Zealand Exploration Ltd, 1992; Field et al., 2006; Archer et al., 2014), and a study of the onshore analogue could provide useful insights into the reservoir architecture at depth (Field et al., 2006). Therefore, our work complements existing studies by considering rocks with different host-rock properties, which are actively targeted by hydrocarbon exploration (Lee and Begg, 2002; Hessler and Sharman, 2018).

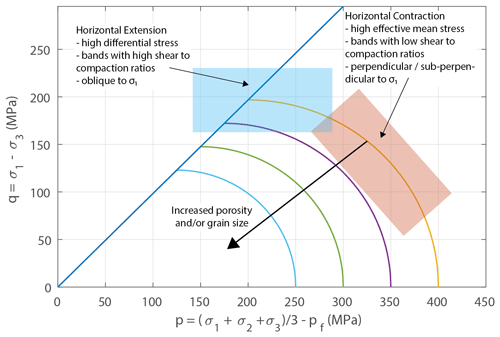

We study faults and deformation bands in the Whakataki Formation, an exhumed turbidite package of the subduction wedge of the Hikurangi subduction zone (Chanier and Ferrière, 1991; Neef, 1992a, b, 1995; Chanier et al., 1999; Field, 2005; Nicol et al., 2007, 2013). The Hikurangi subduction zone initiated ca. 25 Myr ago and accommodates oblique convergence between the Pacific and Australian plates (Fig. 2) (Walcott, 1984; Ballance et al., 1985; Walcott, 1987; Ballance, 1988; Chanier and Ferrière, 1991; Rait et al., 1991; Luyendyk, 1995; Chanier et al., 1999; Nicol et al., 2007; Spörli, 1980; Bailleul et al., 2013; McCoy-West et al., 2013; Mortimer et al., 2017; Strogen et al., 2017).

Figure 2(a) Simplified geological map (Edbrooke, 2017) of New Zealand's North Island, showing the study site location (red star) (coordinates: NZGD 2000, UTM Zone 60S, 5468211 m N, 0430670 m E). (b1) Simplified geological map of the research area. The dominant structures at the field site are NE–SW trending folds and thrust faults with N–S trending normal faults along the coastline. Below are cross sections through the area. A–A′ and B–B′ highlight the asymmetrical fold geometry with synclines resembling box folds and anticlines resembling kink folds. The unconformable overlying Quaternary sediments have not been plotted to highlight the geometry of the folds. C–C′ is a schematic cross section drawn perpendicular to the average strike of normal faults. An arbitrary geological bed has been added to show possible displacements associated with faults. (b2) A detailed map of the fault location and orientation along a ca. 1 km stretch of coastline. Normal faults are dominant, with thrust faults found in areas of low normal-fault density. (b3) Schmidt net with poles to cleavage planes observed in the damage zone of the Whakataki Fault, a large-scale thrust fault associated with the first phase of compression, D1. (b4) Schmidt net of poles to bedding planes. The mean axial plane for all bedding is plotted as great circle (red line). Given that the axial plane trends parallel to the traces of the dominant thrust faults in the area, it is reasonable to assume, by assessing the poles to the axial planes, that the folding was induced by SE shortening. All Schmidt nets are plotted with the Stereonet 10 software of Allmendinger et al. (2011).

The onset of subduction is expressed in the sedimentary record by the widespread deposition of olistostrome deposits in the earliest Miocene (Chanier and Ferrière, 1991; Bailleul et al., 2007, 2013), which also define the base of the studied Whakataki Formation. The basal olistostrome is overlain by deep-marine high-energy flysch deposits (Neef, 1992a), consisting of a succession of laterally continuous fine-grained sandstone and siltstone turbidite beds with total estimated thickness of 900–1500 m (Neef, 1992a; Field, 2005; Bailleul et al., 2013).

The present study is based on field observations and samples collected from coastal exposures of the Miocene Whakataki Formation 5 km SW of Castlepoint, in the Wairarapa region of the North Island of New Zealand (Fig. 2, coordinates: NZGD 2000, UTM Zone 60S, 5468211 m N, 0430670 m E,). The Whakataki Formation (deposited between ca. 25 and 17.5 Ma; Neef, 1992a; Field, 2005; Bailleul et al., 2013; Raine et al., 2015) was emplaced in tectonically controlled confined basins on the lower trench-slope of the subduction margin (Bailleul et al., 2007, 2013). The overall sedimentary succession preserves a record of the onset of subduction associated with horizontal contractional deformation between ca. 25 and 19 Ma (deformation phase 1 – D1), followed by a period of horizontal extension (ca. 15–5 Ma; deformation phase 2 – D2) and renewed contraction from the Pliocene to Holocene (deformation phase 3 – D3) (Chanier and Ferrière, 1991; Chanier et al., 1999; Bailleul et al., 2007; Bailleul et al., 2013). Each deformation phase induced corresponding tectonic structures in the study area (Fig. 2):

D1 induced margin-perpendicular contraction expressed by both landward and seaward emplacement of thrust sheets, gentle folding, and reverse faulting along the Hikurangi margin, with the development of trench-slope basins bounded by structural highs (Chanier and Ferrière, 1991; Rait et al., 1991; Chanier et al., 1999; Bailleul et al., 2013; Maison et al., 2018). The main D1 structure in the field area is the NE–SW trending Whakataki thrust fault that has emplaced the Late Cretaceous Whangai Formation (Neef, 1992a) onto the Miocene Whakataki Formation and acts as the western boundary to the Whakataki Formation in that area (Fig. 2).

D2 induced an overall deepening of the forearc domain (Crundwell, 1987; Wells, 1989), and widespread subsidence involved margin-parallel and margin-perpendicular extension of the subduction wedge accommodated by normal faulting (Chanier et al., 1999; Bailleul et al., 2007, 2013). Tectonic erosion, with associated synsedimentary gravitational collapse, has been proposed to have been responsible for this reversal in stress regime (Chanier et al., 1999; Bailleul et al., 2013). The dominant D2 structures in the field area are ca. N–S striking normal faults.

D3 induced a renewal of dominant margin-perpendicular contraction of the wedge with associated folding, thrusting, and strike-slip faulting (Cape et al., 1990; Chanier et al., 1999; Nicol et al., 2002; Bailleul et al., 2007; Nicol et al., 2007; Bailleul et al., 2013). Also associated with this deformation phase is the uplift and exposure of the coastal ranges (Nicol et al., 2002). At the field site, this deformation phase is expressed by pervasive deformation bands, small thrust faults, and intense folding. Deformation bands have been identified in the Whakataki Formation previously (Nicol et al., 2013). However, they have not been described and analysed in detail.

3.1 Field data

Field mapping covered a 17 km2 area south of Castlepoint (coordinates: NZGD 2000, UTM Zone 60S, 5468211 m N, 0430670 m E), in the Wairarapa region of the North Island of New Zealand (Fig. 2). While significant hinterland mapping took place, coastal outcrops were the focus of the fieldwork because exposure is poor in the hinterland. A detailed sedimentological analysis was conducted on sediments of the uplifted Hikurangi subduction wedge to contextualise the structural data and will be presented elsewhere. Orientations of structural elements including bedding planes (S0), faults, and deformation bands were taken across the area and plotted in lower-hemisphere, equal-area stereograms (Allmendinger et al., 2011). All data are shown with bedding restored to horizontal. The restoration was completed by rotating back from the associated S0 measurement of the bed hosting the structures using Stereonet 10 (Allmendinger et al., 2011). Individual S0 measurements were used rather than fold axes because the folds are non-cylindrical and plunge gently. All data were restored as there is evidence of rotation in almost all features (Fig. 2). Palaeostress analysis of back-tilted faults was completed using Win-Tensor (Delvaux and Sperner, 2003). For this analysis, only faults with unambiguous slip vectors and shear sense were used. The PBT-kinematic-axes method was used to find the orientation of the principal stresses. An assessment of whether faults and deformation bands form a conjugate (bimodal) or polymodal pattern was conducted using a statistical test developed by Healy and Jupp (2018). The test analyses the orientation distribution of the poles to fault planes to distinguish between bimodal and polymodal patterns. Differentiation between bimodal and polymodal is established by first finding the ratio between the eigenvalues of the second-rank orientation tensor of the datasets and secondly by calculating the p value. p values close to zero describe a polymodal pattern with higher values reflecting bimodal patterns. The dihedral angle, the angle bisected by σ1 (Chemenda et al., 2012), between conjugate sets of deformation bands was estimated from a cylindrical best fit to orientation data. The net shear-to-compaction ratio (Ds(net)∕Dc) was calculated using the methods from Soliva et al. (2013) and Ballas et al. (2014). These values are used to define the kinematics of the deformation bands. However, these authors assumed that they cut their samples in the plane spanned by the smallest and largest principal strains, the orientation of which they determined from the rather tightly bimodal orientation patterns of the studied bands. In our case, this approach is more difficult because the orientation distributions are less focused. Therefore, typical geometric section errors in terms of true band width and true shear displacement can be expected.

3.2 Spacing analysis

The spacing analysis was conducted using image analysis on two scales in the mapping area: (1) on macroscopic faults with > 20 cm offset exposed along a 5 km stretch of coastline, and (2) on deformation bands at individual outcrops exposed in sandstone layers. The method used for analysis is a simplified version of the line sampling method outlined in Sanderson and Peacock (2019). Statistical spacing analysis based on photographic mosaics, as opposed to direct field measurements, is used to accommodate the following:

-

geometric bias associated with a poorly consolidated rock package that is commonly characterised by uneven surfaces – photographic imaging can minimise the effects of uneven surfaces by using appropriately oriented photos, whereas manual counting along a tape measure can be difficult on such uneven surfaces;

-

safety – many outcrops are located along cliffs in an intertidal domain and subject to ongoing rock falls. Therefore, to restrict the time spent in these potentially hazardous environments, photographic mosaics were acquired.

By using digital DB maps, hundreds of scan lines can be analysed quickly, thereby minimising potential bias associated with placement of the scan line; moreover, the use of statistical methods is more objective and reproducible than qualitative decisions made in accordance with individual outcrops and relies on digital maps.

For macroscopic fault spacing, the location, dip and dip direction, heave and throw, where possible, and shear-sense were recorded, and faults were plotted onto a map. The spacing of macro-faults was measured along scan lines oriented perpendicular to the average fault strike using the ruler tool in ImageJ (Schindelin et al., 2012). The scan lines were 200 m in length in an E–W orientation (orientation perpendicular to the average fault orientation) and had a 50 m N–S spacing. Due to the oblique relationship between the coastline and the fault strike, scan lines were shifted N after 400 m, with the first scan line located in the SW region of the coastline. A total of 20 scan lines were used to measure the fault spacing, and the median is reported. The use of multiple scan lines minimises, but does not eradicate, measurement errors arising from variation in fault strike and an average strike being used to generate the scan line orientation (Sanderson and Peacock, 2019). Spacing values greater than 20 m were removed from the data, as these points represent artefacts of exposure conditions. Horizontally measured spacing was corrected for the average dip of the faults using the sine transformation (Eq. 3) (Sanderson and Peacock, 2019):

The correction procedure also introduces errors because the faults do not all dip the same way. Moreover, they were not rotated to their original position and orientation in space. However, these are common shortcomings of studying fracture spacing in 2D (Soliva and Benedicto, 2005; Laubach et al., 2018). Here, we are mainly interested in the general shape of the spacing distribution and the order of magnitude of the absolute spacing. Pearson correlation coefficient values were calculated for the correlation between the corrected spacing and the associated cumulative distance from the start of the first scan line. For spacing analysis of deformation bands, outcrops had to meet the following conditions: (1) the outcrop surface was fairly planar, and (2) the deformation bands were striking roughly perpendicular to the outcrop surface. Along the coastal outcrop, 12 locations showing deformation bands within fault damage zones (FDZ bands) and 28 locations with bands showing seemingly regular spacing, not adjacent to faults (non-FDZ bands), were selected. Photographs were taken perpendicular to the outcrop surface. Intersections of the bands with the flat outcrop surface were mapped on a suitable photographic mosaic of the outcrop. For outcrops showing mutually overprinting conjugate sets of non-FDZ deformation bands, the dominant set was analysed.

For spacing measurements of deformation bands in damage zones, the fault was put into the origin of the digitised image. For non-FDZ bands, with apparent “regular” spacing, the first band was treated as the origin of the image. Deformation band clusters were treated as single bands following Main et al. (2000). The resulting maps were exported as a binary image. MATLAB (MathWorks, 2011) was used to obtain spacing statistics along scan lines at a spacing of 1 % of the image height. When the horizontal image dimension was not perpendicular to the traces of the deformation bands in the map, spacing was again corrected with the sine transformation (Eq. 3). Normalisation was completed by dividing the spacing value by the width of the image. This permitted comparison of absolute spacing values between outcrops.

In addition to the analysis of natural deformation band distributions, synthetic images were created to show ideal spacing distributions and to highlight how natural variation in heterogeneous rocks and data collection error can impact the measured spacing of natural samples (see Sect. S10 in the Supplement).

3.3 Microstructural analysis

A total of 20 polished thin-sections from samples of host rock and deformation band were examined by backscattered electron (BSE) imaging using a VP Zeiss Sigma scanning electron microscope (SEM). A 10 nm carbon coat was applied to the samples. The instrument was run using a working distance of 8 mm, an acceleration voltage of 15 kV, and an aperture size of 30 µm with an angle-selected backscattered detector. Images of host rock were taken at 400× magnification and those of deformation bands at 800×. Multiple images were taken with a 5 %–10 % overlap and stitched together to produce ca. 1 mm2 images. Of the 20 samples, 5 were taken from zones showing a regular spacing of D3 deformation bands with zero to minimal apparent offset. The remaining 15 samples were from fault damage zones: 10 from D2 damage zones and 5 from D3 damage zones (Fig. 2). For each sample, the host rock and deformation band were analysed in the same thin section. Samples were selected from different locations along the coastline in attempts to analyse a broad range of lithologies. Sample locations of bands with a regular spacing are more clustered, as these were the most appropriate outcrops with good exposure of the facies hosting non-FDZ bands.

BSE maps were analysed for porosity and mineralogy of the samples. Grey-level slicing was used to extract four different phases from the images: (1) porosity; (2) quartz; (3) feldspar; and (4) “other”, which includes reflective oxide components, micas, and clays. For porosity phase analysis, the images were eroded and dilated to generate upper and lower bounds for the estimate (Liu and Regenauer-Lieb, 2011). Grain size estimates were obtained through manual tracing of grains from SEM images in ImageJ (Schindelin et al., 2012). An average of 100 grains were traced for the host rock and the deformation band of each sample, and the equivalent circle diameter was calculated for each polygon.

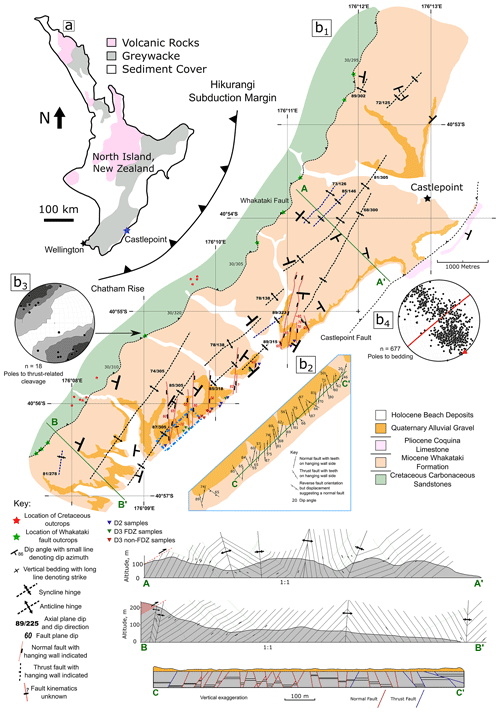

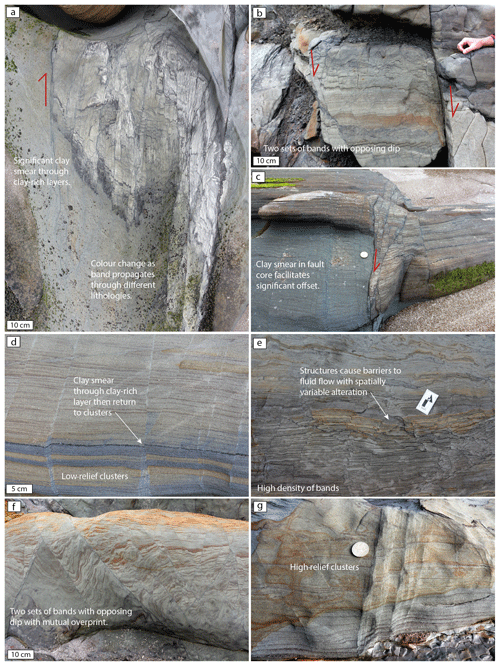

4.1 Rock descriptions and structure

All three regional deformation phases identified in earlier research and presented above (Sect. 2) can be recognised in the Whakataki Formation. Expressions of the deformation in the Whakataki Formation include folds, faults, and deformation bands. Deformation bands are most common within sandier units in areas characterised by equal sandstone-to-mudstone ratios or in areas where sandstone beds are dominant. In areas dominated by mudstone, bands are less common. Figure 3 shows examples of a sand-dominated facies and a facies characterised by equal proportions of sandstone and mudstone.

In the following, we describe structures associated with each tectonic phase. Throughout this description, we use Anderson's nomenclature (Anderson, 1951) where the normal-faulting regime reflects a (sub-)vertical σ1 (horizontal extension) and a thrust-faulting regime reflects a (sub-)horizontal σ1 (horizontal contraction).

Figure 3Field images of the different facies of the Whakataki Formation that dominantly host deformation bands and faults. (a) An outcrop-scale image of a sandstone-dominated sequence cut by a normal fault with ca. 1 m displacement. (b) An outcrop-scale image of a sequence characterised by equal ratios of sand and mud cut by multiple normal faults. This sequence contains more faults than sandier sequences.

4.2 D1 horizontal contraction

4.2.1 Faults and folds

The main regional fault associated with D1 horizontal contraction is the NE–SW trending Whakataki thrust fault (Fig. 2) (Bailleul et al., 2013; Maison et al., 2018). Rare exposures of the thrust damage zone contain slip planes which indicate a NW dip (30∘). NE-trending kilometre-scale folds in the hinterland define the topography (Fig. 2). With poor hinterland exposure, it is not possible to determine the timing of large-scale fold nucleation. Regional studies indicate that large-scale folding was occurring during D1 and that these folds were tightened to their current morphology during D3 (Cape et al., 1990; Chanier et al., 1999; Bailleul et al., 2013). Rare metre-scale, NE-trending upright, moderately NE–SW-plunging, open F1 folds are still preserved in the area (Fig. 4a, e).

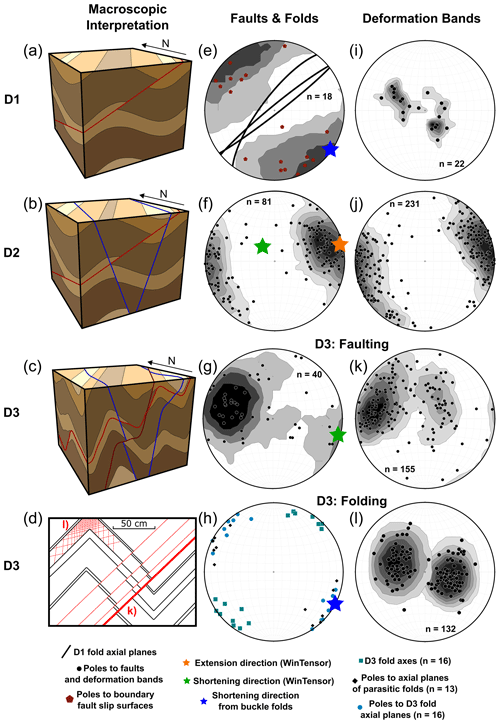

Figure 4Tectonic evolution of the mapping area with each tectonic regime, with corresponding structural data for each phase. (a, b, c) Schematic block diagrams of each deformation phase. (d) Sketch of deformation associated with D3. During D3, two clear distributions of deformation bands are observed: deformation bands associated with faults and deformation bands observed far from faults. Deformation bands observed in D2 are characterised by the same orientations as D3 DBs associated with faults (k). (e) Schmidt net of D1 parasitic fold orientations (planes) with poles to slip surfaces observed in the damage zone of the large-scale Whakataki thrust fault. (f, g) Schmidt nets of fault orientation data from D2 and D3 deformation respectively. σ1 is indicated by the green star. σ3 is indicated by the orange star. (h) The orientation of F3 folds. When compared with F1 axial planes observed in panel (e), the similar orientations of the principal stresses in D1 and D3 are highlighted. The blue star represents the shortening direction, estimated from the pole to the average fold axial plane. (i) Poles to D1 deformation bands. (j) Poles to D2 deformation bands. (k) Poles to D3 fault damage-zone-associated deformation bands. (l) Poles to D3 deformation bands that are not located in fault damage zones. The similarity of the fault and fault-associated deformation band orientations indicates that they formed in the same stress field. Also, axial plane data from D3 align with D3 non-fault damage-zone-associated bands as shown in panel (l). All deformation band and fault data are back-tilted as there is evidence of folding occurring coeval to, or later than, all events. Stereoplots were produced using Stereonet 10 software (Allmendinger et al., 2011). Palaeostress analysis completed using Win-Tensor (Delvaux and Sperner, 2003).

4.2.2 Deformation bands

D1 DBs are rare and are distinguished from D2 and D3 DBs through cross-cutting relationships (Fig. 5a, b, c). The orientation distribution of D1 DBs can be considered bimodal with a p value of 0.5. D1 DB dihedral angles range from 65 to 84∘ with a mean of 73∘. With bedding restored to horizontal, DBs trend 037∘ (Fig. 4i). The set dipping SE has a dip angle of 40∘ and the set dipping NW dips at 26∘ (Fig. 4i). When bands pass through beds with thin clay-rich layers, they have a dark colour without relief. In beds with lower clay content, bands show high to moderate relief and are lighter in colour (Fig. 5a, b). The width of bands ranges from 0.2 to 0.5 mm. Bands can extend for metres along strike. Eye and ramp structures are present. However, single strands are most commonly observed (Antonellini and Aydin, 1995). Offset associated with the bands is variable, with some characterised by minimal offset, whereas others accommodate reverse shear offsets at the millimetre scale. Conclusively, these observations suggest that these bands are CSBs and shear-enhanced compaction bands (SECBs) formed during D1 horizontal contraction (Ballas et al., 2014; Fossen et al., 2018; Schultz, 2019). The rarity of D1 deformation bands does not permit for meaningful spacing analysis.

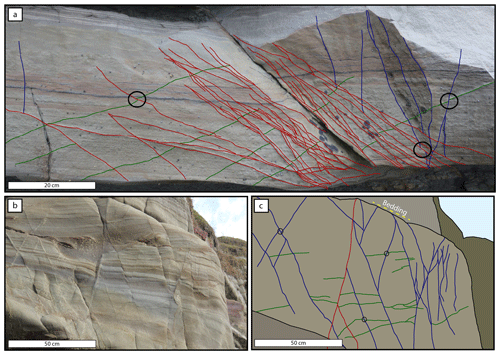

Figure 5Examples of overprinting criteria used to determine the relative timing of each deformation phase. (a) Multiple generations of deformation band located within a D3 damage zone. The digitisation indicates the different generations of deformation band with overprints used to generate relative timing highlighted by black circles (green denotes D1, blue denotes D2, and red denotes D3). (b) Multiple generations of deformation band with overprints. A line drawing to highlight the overprints observed in panel (b) is shown in panel (c) (green denotes D1, blue denotes D2, and red denotes D3). Black circles in panel (c) signify some examples of overprints.

4.3 D2 horizontal extension

4.3.1 Structures and relative timing

Field overprinting criteria demonstrate that an extensional event followed D1 horizontal contraction (Fig. 5a, b, c) (Chanier et al., 1999). Overprinting relations include the displacement of F1 fold hinges by D2 normal faults and normal-sense shear displacement of D1 deformation bands by D2 deformation bands (Fig. 5a, b, c). The structures associated with D2 are (1) normal faults, (2) deformation bands with clear normal-sense offset, and (3) deformation bands with minimal offset (Figs. 2, 5a, 6, 7).

4.3.2 Faults

Normal faults are the main structures associated with D2 (Fig. 3a, b). They trend NNW with an average dip angle of 69∘ (Fig. 4f). Analysis of the fault pattern shows that it is polymodal with a p value of 0.001 (Healy and Jupp, 2018). While polymodal across the field area, normal faults are commonly observed as two sets with opposing dips at individual outcrops (Fig. 4f). Fault displacement ranges from tens of centimetres to tens of metres. Many D2 faults have displacements of ca. 1 m (e.g. Fig. 6a). The limited vertical extent of the cliff exposures and poor hinterland exposure preclude estimates of upper-bound displacement (Fig. 3a, b). Fault length can also not be determined as they generally extend beyond cliff height. The faults are dominantly brittle, with gouge present in the core of larger faults (Figs. 3, 7a, b).

Figure 6(a) Outcrop image of a normal fault hosted within a mudstone-rich sequence. The fault accommodates ca. 1 m of displacement in the image plane. The displacement is distributed throughout multiple slip surfaces, narrow slip zones, and dense arrays of shear bands hosted within a high-strain zone. Adjacent to the high-strain zone are deformation bands and shear bands with similar and opposing dip. All structures accommodate normal-sense shear displacement. (b) The compactional shear bands accommodate displacement and can link to form a dominant slip surface. DBs have a darker colour compared with the host rock and recessive relief. Sedimentary layering is displaced with normal-sense shear offset. Within the high-strain zone, DBs dominantly share the same orientation as the fault displacement. However, bands with variable orientations are present indicating high strain within the zone.

Palaeostress analysis of 16 back-tilted normal faults indicates ENE–WSW extension (σ1: 62/298∘ and σ3: 23/080∘) (Fig. 4f), consistent with the more comprehensive D2 palaeostress analysis presented by Chanier et al. (1999) for the east coast of the North Island.

4.3.3 Deformation bands

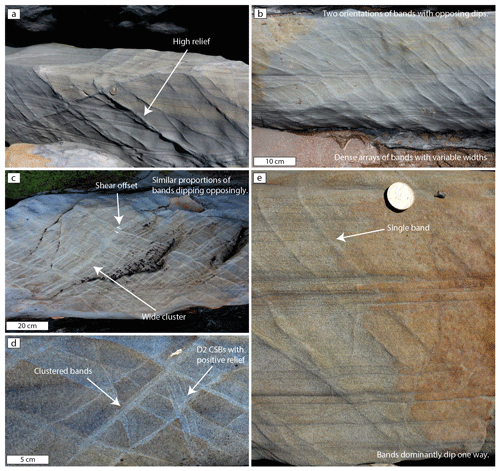

D2 deformation bands are primarily observed in the damage zones of D2 faults (Fig. 7a, b, c). However, some single bands are observed between faults (Fig. 7d). They are generally darker in colour compared with the host rock and show no or negative relief (Fig. 7a–f). When suitable host-rock layers are present, clay smear is common (e.g. Fig. 7a, c). When propagating through layers rich in shell hash or coarser grains with less lithological heterogeneity, the bands show positive relief (Fig. 7g). The average trend of bands is 340∘, with two sets of poles spanning finite arcs dipping steeply NE and SW (Fig. 4j) (average dip angle is 75∘). Band orientation is ca. 20∘ to the σ1 value reported by Chanier et al. (1999). However, angles ranging from 10 to 40∘ are present. This is indicative of CSBs with large shear components. Data are compared to the σ1 value reported by Chanier et al. (1999) for the Wairarapa because it is calculated from the analysis of a larger dataset. The bands most commonly occur as single bands; however, clusters restricted to sandstone beds are also observed (Fig. 7d, g). Clusters localise into single strands if they propagate into adjacent mudstone beds (Fig. 7d). Band thickness ranges from 0.1 to 0.35 cm (Figs. 6b, 7), with an average thickness of 0.16 cm. Thicker bands are common in sandier layers and exhibit positive relief (Fig. 6a). Thickness variations are present in the bands as they propagate through different lithologies (Fig. 7g). The length of bands is typically on the order of tens of metres. Many D2 bands extend beyond the outcrop scale, making accurate estimates of length impossible. Bands hosted in areas dominated by sandstone beds, with only very thin mudstone intervals, extend beyond the outcrop scale through the mudstone. In areas characterised by thicker mudstone intervals, bands are restricted to sandstone intervals. Displacement associated with the bands generally ranges from 0 to 4 cm with a mean displacement of ca. 1 cm. Bands without apparent offset are rare and may be an artefact of a sectioning effect (Soliva et al., 2013). Pattern analysis of the band orientation distribution shows that bimodality can be rejected with a p value of 0.01 (Healy and Jupp, 2018). However, when band orientations are analysed from individual outcrops, bimodality is present. The dihedral angle of bands from individual outcrops ranges from ca. 30 to 60∘, which is indicative of CSBs. While bands can accommodate several centimetres of offset, microstructural analysis confirms that shear displacement occurs with compactional strain. Therefore, while the range of dihedral angles and the angles to σ1 may indicate shear bands, porosity and grain size reduction within the bands confirms that they are CSBs, often with large shear components.

Figure 7Outcrop images of faults and deformation bands associated with normal faulting. (a) High density of normal-sense shear bands characterised by several centimetres of offset. The bands are hosted in the damage zone of a fault with > 10 m offset. Offset cannot be constrained due to exposure conditions. The bands change colour as they propagate through different parts of the host rock with bands towards the top of the image characterised by darker colours after passing through clay-rich layers. To the left of the image, a slip surface (red arrow) removes the clay-rich layer from the image plane. (b) An interaction damage zone between two normal faults. Deformation bands within the damage zone have low relief and a darker colour than the host rock, indicating clay incorporation into the band. (c) Normal-fault plane with a damage zone comprising many deformation bands that are darker in colour than the host rock and exhibit negative relief. (d) Lighter-coloured normal-sense shear bands characterised by low relief. As a cluster propagates through a clay-rich layer, it reduces in width to a single surface. (e) High density of normal-sense shear bands causing the host rock to be significantly compartmentalised. This is supported by the variable colour of the host rock, indicating that later fluid flow is localised and restricted. (f) A dense array of two sets of normal-sense shear bands. All examples cut S0 and, thus, allow shear-sense determination. (g) Cluster of normal-sense compactional shear bands characterised by high relief and <1 cm offset.

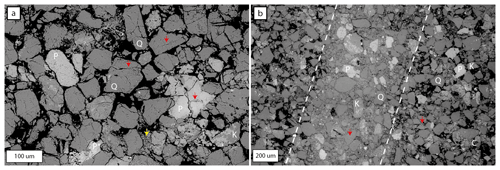

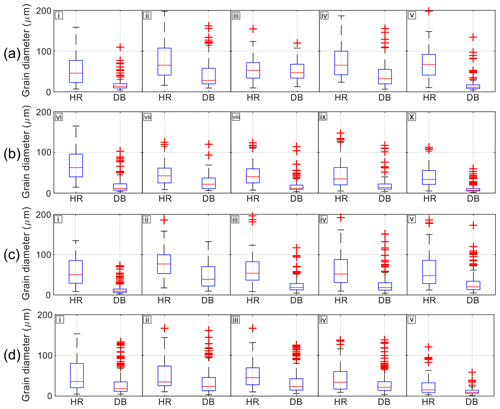

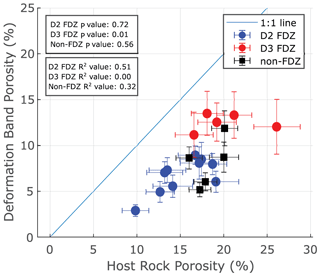

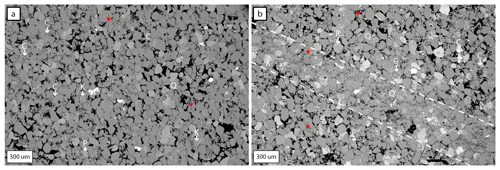

At the microscale, D2 bands are characterised by a reduction in grain size and porosity compared with the host rock which makes the bands easy to identify under the microscope (Figs. 8a, b, 10). The bands show diffuse borders with the surrounding host rock (Fig. 8b). The grain size distribution of deformation bands generally shows positively skewed distributions with a lower median value compared with the host rock, indicating a reduction in grain size due to cataclasis (Fig. 9a) (Fossen et al., 2007; Balsamo et al., 2010). The median grain equivalent circular diameter in deformation bands is 37 µm compared with 57 µm in the host rock, showing a 35 % reduction (Fig. 9a). Deformation bands also show a smaller range in grain size at 156 µm (ranging from 9 to 165 µm) compared with 231 µm in the host rock (ranging from 8 to 239 µm), with the host rock preserving larger grains (see Sect. S8). Deformation bands, compared with the host rock, are characterised by a high matrix content, due to grain size reduction, and a concentration of clay-sized grains, permitting the distinction between the two (Fig. 8a, b). The amount of matrix decreases from the centre to the outside of the bands and becomes almost non-existent in the host rock, which is dominated by intact grains, with/without intragranular fractures, zones of increased clay content, and pore space. There is an average absolute porosity reduction of 8 % (from ca. 13 % in the host rock to ca. 5 %) in deformation bands (Fig. 10). This equates to a 59 % relative porosity reduction. Relict medium-sized pores (30–50 µm) are present within some bands, accounting for much of the remaining ca. 5 % porosity (Fig. 8b). By using porosity reduction as a proxy for inelastic volumetric strain, we obtain a ratio of DS∕DC that ranges from ca. 20 to >100, which is indicative of CSBs with large shear offset (Soliva et al., 2013; Ballas et al., 2014; Soliva et al., 2016; Fossen et al., 2018). Generally, the darker-coloured bands containing higher concentrations of clay have higher DS∕DC ratios, as indicated by shear displacement observed at the outcrop scale (e.g. Fig. 7a, b, f). Grain fracture is observed at grain contacts and within grains in both host rock and in deformation bands (Fig. 8a, b). The presence of microfractures in the host rock shows that the deformation is not solely concentrated within deformation bands. Due to a reduction in grain size, a significant reduction in porosity and a low density of microfractures, D2 deformation bands are classified as cataclastic CSBs (Antonellini et al., 1994; Mair et al., 2000; Fossen et al., 2007; Ballas et al., 2015).

Figure 8BSE images of D2 normal-sense compactional shear bands and associated host rock. (a) A normal-sense compactional shear band hosted within less deformed host rock. The white dashed lines indicate the edge of the deformation band. Deformation bands associated with D2 horizonal extension have diffuse edges and are characterised by reduced porosity and an increased clay content. The red arrows denote the location of microfractures. Microfractures are observed in grains within the deformation band and within the host rock. The host rock is characterised by higher porosity compared with the deformation band. Panel (b) is an image of host rock sampled within 5 cm of a normal-sense deformation band. Within the host rock, microfractures are present, with some examples highlighted by red arrows. In addition, pockets of smaller grain size can be seen with higher clay content, indicating the lithological heterogeneity of the unit. Such an example is indicated by the yellow arrow. Q denotes quartz, C denotes zones of clay-sized particles, K denotes potassium feldspar, P denotes plagioclase, and P* denotes deformed plagioclase.

Figure 9Box-and-whisker plots to show the difference in grain size distribution in deformation bands compared with host rock. (a) Grain size distributions associated with deformation bands located in D2 fault damage zones. (b) Grain size distributions associated with deformation bands located in D3 fault damage zones. (c) Grain size distributions associated with D3 non-FDZ deformation bands. For each sample, the interquartile range and the median are smaller in the deformation bands compared with the host rock. The tops and bottoms of each box are the 25th (Q1) and 75th (Q3) samples respectively. The centre line represents the median. The whiskers are drawn from the ends of the interquartile ranges to the adjacent values (Q1 − 1.5 ⋅ interquartile range, and Q3 + 1.5 ⋅ interquartile range). Data that lie beyond the whisker length are outliers (red crosses).

Figure 10(a) Measured host-rock porosity (%) plotted against porosity measured in the deformation band (%). Each data point represents a thin section where porosity was measured in the host rock and deformation band. All deformation bands exhibit a reduction in porosity compared with the host rock. The p value refers to the Pearson correlation coefficient value. The R2 value (R-squared) represents the variance from a best fit. Raw statistical data are shown in Sect. S7.

4.4 D3 horizontal contraction

4.4.1 Structures and relative timing

Field overprinting criteria show that a contractional event followed D2 horizontal extension (Fig. 5a, b, c) (Chanier et al., 1999). Macroscale D3 overprinting relations include folding-induced dissection of D2 faults at bedding interfaces through flexural shear of and slip along weak mudstone layers; multiple generations of slickenfibre veins in D2 faults where strike-slip orientations overprint dip-slip ones; cross-cutting of D2 faults by D3 thrusts – easily observed along the coast (also observed at the deformation band scale) (Fig. 5a, b, c); and rotation of D2 faults around F3 fold hinges. These relations have also been described by Chanier et al. (1999) for the east coast of the North Island.

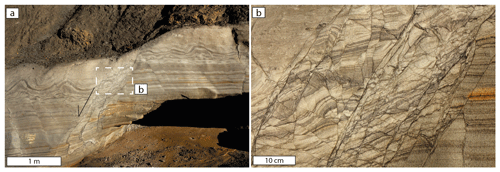

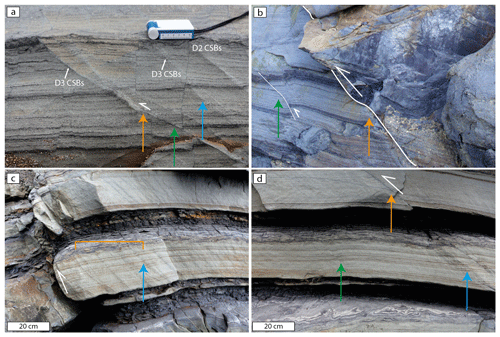

The structures associated with D3 are (1) folds, (2) reverse faults, (3) deformation bands with constant spacing and minimal to no offset (Figs. 11, 12), and (4) reverse-sense deformation bands located in the damage zones of faults (Figs. 13, 14). Field overprinting criteria cannot be used to discern the relative timing of these structures during this contractional phase, as all structures are not seen interacting in a single outcrop. The structures have a similar orientation to D1 structures (Fig. 4).

Figure 11Field images of regularly spaced D3 SEBCs and D3 CSBs. CSBs are differentiated from SECBs by their millimetre- to centimetre-scale offset. Regularly spaced bands are primarily hosted within single sandstone layers and do not propagate into adjacent layers. (a) Two orientations of D3 SECBs with high relief that exhibit undulations along strike. (b) Two orientations of D3 SECBs. The D3 SECBs are dense and have variable thickness. Narrow SECBs with moderate relief sit between thicker SECBs and clusters. (c) Densely spaced D3 SECBs. Similar proportions of SECBs with each dip are observed. Through the centre of the image is a wide cluster of SECBs. CSBs with reverse-sense offset cut the cluster. (d) Wide clusters of D3 SECBs. The SECBs cut high-relief D2 CSBs. (e) Single-band SECBs that dominantly dip one way often with <1 mm or no macroscopic offset of sedimentary layers.

Figure 12BSE images of host rock surrounding D3 SECBs and a D3 SECB characterised by minimal shear offset. Macroscopically, these bands have a periodic spacing and are distal to fault planes. (a) BSE image of host rock located within 5 cm of an SECB. Within the host rock, clusters of clay-sized particles and fragmented host-rock grains are present. Pore space is visible between grains. Microfractures are present in host-rock grains (examples are indicated by red arrows). (b) SEM image of a D3 SECB (borders marked by white dashed lines) hosted within less deformed host rock. The band has diffuse edges and is characterised by a reduction in porosity and an increase in clay content compared with the surrounding host rock. Towards the edge of the band, porosity is better preserved, indicating the diffuse nature of the band edges. Many host-rock grains within the band are preserved, with little to no reduction in grain size. These grains are surrounded by fragments of host-rock grains that are generally clay-sized. Q denotes quartz, C denotes zones of clay-sized particles, K denotes potassium feldspar, and P denotes plagioclase.

4.4.2 Faults and folds

Upright, NE–SW trending folds with 100 m scale wavelengths and along-strike extents of several kilometres constitute the most obvious large-scale D3 structures (Fig. 2). Fold axes are shallowly dipping (ca. 10∘) and doubly plunging NE and SW (Fig. 4h). Unlike many F1 folds, F3 folds are asymmetrical, with steeper eastern limbs and non-cylindrical geometry (Fig. 2). Synclines commonly have open hinges and resemble box folds in their geometry. Anticlines resemble kink folds with closed hinges and long straight limbs. Higher-order parasitic folds with matching geometry are observed throughout the mapping area and are best exposed in road cuts in the hinterland (Fig. 4h). The difference in the geometry of F1 and F3 folds indicates that there were two folding events. However, due to the similar orientations of structures accommodating D1 and D3 deformation, it is not possible to state whether F3 folds represent tightened F1 folds or if they have nucleated solely during D3 horizontal contraction. Within fold limbs, layer-parallel slip and shear can be observed in interbedded mudstone layers, along with thinning out of these layers. Slip surfaces with slickenfibre veins exhibit opposing shear sense on opposing fold limbs. These observations could be associated with both bending and buckling folding mechanisms (Donath and Parker, 1964; Chapple and Spang, 1974). Given the fact that F3 axial planes trend parallel to the traces of the dominant thrust faults in the area, it is reasonable to assume, by assessing the poles to the axial planes, that F3 folds formed by SE shortening (Grujic and Mancktelow, 1995). This is consistent with the shortening direction indicated by regional thrust faults (Chanier et al., 1999).

D3 reverse faults can be observed along the coastline (Figs. 2, 13). Reverse faults are less commonly observed than D2 normal faults. Poor hinterland exposure prevents their observation away from the coastline. Fault length is often indiscernible as they extend beyond cliff height (> 10 m). However, some are shorter than the cliff face (<10 m in length). Fault displacement ranges from 0.2 to 5 m and is ca. 1 m on average (Fig. 13). Reverse faults trend NNE–SSW with an average dip of 48∘ (Fig. 4g). The orientation of reverse faults is subparallel to the coastline. This generates observational bias when assessing the pervasiveness of reverse faults. A dominant set dips ESE, and a secondary set dips WNW. Statistical analysis shows that the fault orientations are not distributed bimodally (Healy and Jupp, 2018). D3 reverse faults are brittle structures with cataclastic fault cores and occasional gouge. Palaeostress analysis of back-tilted D3 reverse faults with slickenfibre veins and shear sense is consistent with the literature and is in alignment with the present-day movement of the Pacific plate (σ1: 01/092∘) (Fig. 4g) (Chanier et al., 1999; Bailleul et al., 2013). We have analysed back-tilted D3 faults because deformation bands in the damage zone of these faults mutually cross-cut conjugate D3 bands with no apparent offset, and orientation analysis of the latter shows that they have been passively rotated during folding (see Sect. S4). However, we cannot rule out that faulting could have occurred anytime during D3, especially in steep fold limbs when deformation can no longer be accommodated by folding. We do not have evidence for this as most of the fieldwork took place at coastal outcrops that are in the gentle to moderately dipping back-limb of a syncline.

Figure 13Images of reverse-sense deformation bands and D3 reverse faults. (a) Reverse-sense compactional shear bands are observed. When propagating through clay-rich layers, the bands accommodate several centimetres of offset (orange arrow). Bands are characterised by low relief when darker than the host rock in colour (green arrow). When characterised by higher relief, the shear displacement magnitude decreases (blue arrow). Within the image, D2 CSBs are observed to be offset by D3 CSBs. (b) A D3 reverse fault (orange arrow) with an associated damage zone that comprises compactional shear bands that accommodate reverse offset in orientations that match the main fault plane (green arrow). (c) A D3 reverse fault with the associated damage zone. The DBs within the damage zone do not show a clear decay in spacing (orange bracket) suggesting that periodically spaced structures may represent the first stage of deformation and then faults can propagate from the linkage of pre-existing bands. The DBs mainly comprise clusters with reverse-sense shear offset (blue arrow). (d) An image of the beds shown in panel (c). Panel (d) was taken 2 m to the right of panel (c). Here, a slip surface can be seen that is characterised by a darker colour (orange arrow) compared with adjacent deformation bands that have a higher relief and are clustered (blue arrow). The green arrow highlights pre-existing D2 CSBs that have been incorporated into the damage zone of the fault shown in panel (c). The incorporation of clay into the slip plane seems to promote shear localisation and failure.

4.4.3 Deformation bands

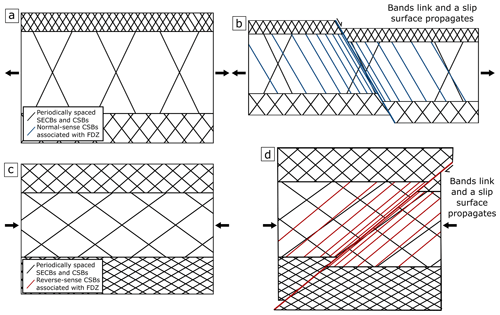

When comparing the dihedral angle and DS∕DC ratio, two types of deformation bands are associated with D3: reverse-sense CSBs and SECBs. SECBs are the most common.

D3 DBs not associated with fault zones

SECBs are mainly hosted in areas dominated by sandstone beds, with less interbedded mudstone. SECBs primarily form single bands (Fig. 11e) but also occur in narrow clusters in areas with higher band densities (e.g. Fig. 11d). On average, single bands are 5 mm in width with a range from 0.26 mm to 1 cm. Clusters are on average 2 cm wide. Eye and ramp structures can be recognised in the networks. The bands are lighter in colour than the host rock and show positive relief (Fig. 11). SECBs exhibit no observable shear displacement, except where clusters are present and millimetre offset can be observed. Rare CSBs are present within zones of SECBs. The CSBs are identified by the associated millimetre-scale macroscopic offset of pre-existing structures and sedimentary layering. Some bands pass through multiple beds and can extend beyond the scale of exposure. Most commonly, however, SECBs are confined to individual sandstone and siltstone beds where they form conjugate bands that strike NNE and have opposite dips (Figs. 4l, 11). When comparing back-tilted orientation data with present orientations, analysis from 11 outcrops indicates that there is a tighter clustering of band orientations after back-tilting, suggesting that SECBs formed before fold tightening or initiation. In addition, band orientations mapped on the same bed across a fold hinge lie on the same great circle, suggesting that these bands predate F3 folding (see Sect. S4). Pattern analysis shows that most SECBs have a bimodal orientation distribution and can be considered as conjugate sets (Healy and Jupp, 2018). The average dihedral angle is 82∘ (after back-tilting), ranging from 68 to 89∘.

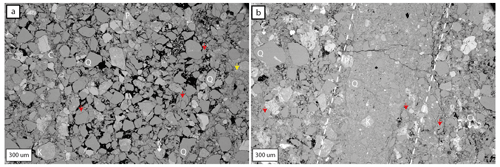

Microscopically, SECBs have diffuse borders with the surrounding host rock (Fig. 12a, b). The bands are characterised by a reduction in grain size and porosity (Fig. 10, 12b). The host-rock median grain size is 39 µm, and the deformation band median grain size is 22 µm, representing a 44 % reduction (Fig. 9c). The range in grain diameters inside and outside of the bands is similar: 157 µm for deformation bands (ranging from 5 to 162 µm) and 162 µm for host rock (ranging from 4 to 166 µm). However, the interquartile range is much less for deformation bands: 49 µm for host rock and 27 µm for deformation bands. This small range for deformation bands results in many outliers, indicating relict host-rock grains within the bands (Fig. 9c). Grain size within the bands has a unimodal, positively skewed distribution, indicating cataclasis with a larger number of smaller grains. Positive skew suggests that not all grains have been equally fractured. SECBs are only observed in rocks with > 15 % host-rock porosity (Fig. 10). The porosity within the deformation bands, on average, decreased from 18.5 % in the host rock to 8.8 %, a relative reduction of 52 % (Fig. 10). Microfractures are observed in host-rock grains and DB grains (Fig. 12a, b). Within the bands, there is a cataclastic fine-grained matrix comprising clay-sized particles of fragmented quartz, feldspar, and lithic grains, which is generally absent in the host rock (Fig. 12a, b). Analysis of compaction versus shear shows an average DS∕DC value of 0.83 for SECBs, ranging from 0.2 to 1.5. This value shows that compaction and shear magnitudes are similar; therefore, the bands are microscopically classified as cataclastic SECBs (Ballas et al., 2015).

D3 DBs within fault damage zones

D3 reverse-sense CSBs are dominantly observed within the damage zone of reverse faults. However, SECBs are also present within fault damage zones. CSBs are very similar in macroscopic appearance to SECBs, often with high relief and a lighter colour compared with the host rock (Fig. 13a, c, d). CSBs, unlike SECBs, are consistently characterised by macroscopically visible shear offset. Fault-related CSBs resemble D2 CSBs when bands propagate though muddy layers and clay smear is present (Fig. 13b). They mainly occur as single bands but also in clusters (Fig. 13). Single bands are on average 5 mm wide and range from 3 to 7.5 mm. Clusters are ca. 2–3 cm in width (e.g. Fig. 13c). CSBs accommodate millimetre- to centimetre-scale reverse offset (e.g. Fig. 13a). In clay-rich host rocks, the bands can accommodate several centimetres of offset, indicating that some bands are CSBs with large shear offset (Fig. 13b). The bands trend NNE with one poorly clustered dominant set dipping ESE (Fig. 4k). The dominant set dips ESE at 63∘ and the less dominant set dips WNW at 29∘. This orientation is very similar to D3 faults indicating that they formed in the same stress field. The SECB orientation does not match with fault orientation as strongly (Fig. 4g, l). The bands generally propagate for multiple metres and extend out of outcrop observation, similar to D2 normal-sense deformation bands. However, some terminate against thicker mudstone intervals. Pattern analysis of all CSBs measured across the field site rejects bimodality in CSBs associated with faults, suggesting a polymodal orientation distribution (Healy and Jupp, 2018). However, when analysed at individual outcrops, pattern analysis suggests that the bands are bimodal with dihedral angles ranging from 51 to 80∘.

Microscopically, CSBs are characterised by diffuse edges (Fig. 14a, b). These bands show the largest reduction in grain size of all deformation bands observed at the field site. The median host-rock grain size is 57 µm compared with 21 µm in the deformation bands – a reduction of 63 %. The total range in grain size is similar for the host rock and deformation bands: 228 µm for the host rock (ranging from 8 to 236 µm) and 224 µm for the deformation band (ranging from 4 to 228 µm). However, the interquartile range is considerably different: 54 µm for host rock and 22 µm for the deformation band (Fig. 9b). This variation is similar to that seen in the D3 SECBs. As with the other bands, D3 CSBs have a lower porosity than the host rock, 20 % outside of the band and 12.3 % inside the band – a reduction of 39 % (Fig. 10). This is the smallest reduction in porosity observed across the varieties of deformation band. Pore space in deformation bands is filled with fragments of grains and clay minerals (Fig. 14b). Grains within the bands and the host rock show intragranular fractures radiating from grain contacts (Fig. 14a, b). Compaction and shear analysis show that the Ds∕Dc value is 63, ranging from 32 to 106. This, as with D2 bands, indicates considerably more shear strain than compaction, and characterises the bands as CSBs, often with large shear offset. The grain size reduction, as indicated by the interquartile range, indicates that many are cataclastic CSBs.

Figure 14(a) BSE image of host rock located <5 cm from a D3 reverse-sense compactional shear band hosted within the damage zone of a reverse fault with an offset of <1 m. Pore space is clearly observed in the host rock. Within the host rock, regions of higher concentrations of fragmented grains are present (yellow arrow). This highlights the heterogeneity of the host rock. Microfractures are present within host-rock grains (examples are indicated by the red arrows). (b) BSE image of a deformation band associated with a D3 reverse-fault damage zone of a fault with <1 m offset. Dashed lines denote the boundaries to DBs. The band is characterised by reduced porosity and grain size compared with the host rock. The edge of the band is diffuse with a gradual increase in porosity into the host rock. The pore space within the band is filled with fine-grained fragments of deformed host-rock grains. Microfractures are observed within the preserved host-rock grains within the DB (red arrows). A potentially late extension fracture cuts across the deformation band and does not appear to propagate into the host rock. Q denotes quartz, C denotes zones of clay-sized particles, K denotes potassium feldspar, and P denotes plagioclase.

4.5 Spacing

4.5.1 Synthetic spacing

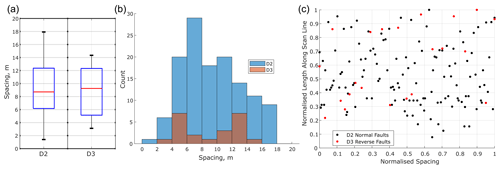

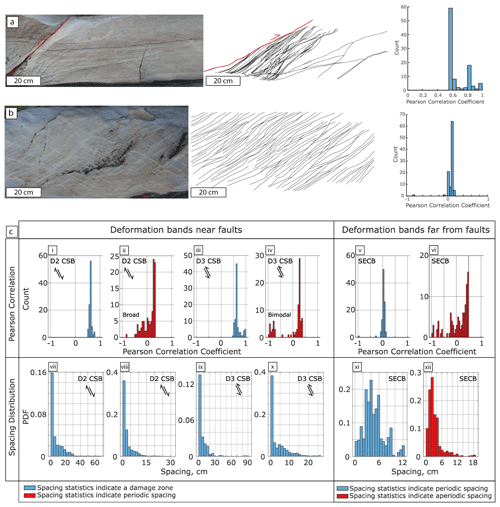

Synthetic spacing images analysed in Sect. S10 serve as an interpretative guide for the natural spacing distributions. The key outcomes of the brief analysis of the synthetic spacing images can be summarised as follows. Three end-member spacing distributions are obtained: (1) distributions characterised by Pearson values of 1 or close to 1 with positively skewed absolute spacing distributions, (2) distributions characterised by Pearson values of 0 or near-zero with a Gaussian distribution of absolute spacing values, and (3) distributions characterised by widely distributed Pearson values ranging from −1 to 1, commonly accompanied by a positively skewed bimodal distribution. Case 1 indicates that spacing varies systematically in space, which is characteristic of a fault damage zone with monotonously increasing DB spacing away from the fault. Case 2 represents constant DB spacing with noise, as seen in pervasively distributed DB far away from faults. Case 3 is obtained for a superposition of 1 and 2 and represents multiple deformation events affecting the same bed.

4.5.2 Natural spacing

Map scale

Analysis of the location of the macroscale faults, with displacements greater than 20 cm, show that many have a similar spacing (Fig. 15). D2 faults have a positively skewed distribution with a skewness value of 0.3. The median spacing of the 114 D2 faults analysed is 8.7 m when corrected for true spacing. The Pearson correlation coefficient for the spacing against distance is −0.07, with an analysis conducted from SW to NE. D3 faults have a bimodal distribution indicating two primary spacing populations with modes of 5 and 13 m when corrected for true spacing. Skewness for the 41 analysed D3 faults is 0.03. The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.44. Pearson values <0.5 indicate that there is no correlation between the spacing and location of normal or reverse faults.

Figure 15(a) Box-and-whisker plots of the corrected spacing distribution of D2 normal faults and D3 reverse faults. (b) Histograms of the corrected spacing distribution of D2 normal and D3 reverse faults. A normality test (Lilliefors test; MathWorks, 2011) shows that D2 has a normal distribution, while normality is rejected for D3. D2 shows a positive skew, and D3 has a bimodal distribution. (c) The plot of the normalised spacing against distance from the start of the scan line for normal and reverse faults. The plot most closely resembles Fig. 15b and f.

Deformation band spacing

Qualitatively, deformation bands in the mapping area appear to exhibit two spacing distributions. Generally, those associated with faults (both normal sense and reverse sense) form fault damage zones with a variable distribution (Figs. 6, 7, 13) where spacing increases with distance from the fault plane. Damage zone width varies greatly along faults and from fault to fault. The maximum width of the damage zone is identified by a return to a background level of damage. Some damage zones can extend for up to 5 m before interacting with the damage zone of an adjacent fault, while other beds along the same fault show no macroscopic damage zone. The second spatial distribution is a regular spacing. Regular spacing is generally observed when there is no fault nearby (Fig. 11). Regularly spaced bands are also observed in damage zones as a separate pattern to bands with variable spacing (e.g. Fig. 13c). Quantitatively these observations were tested with the hypotheses: bands observed adjacent to a fault plane have a positive correlation between spacing and distance from the fault plane and bands not observed adjacent to a fault plane have no relationship between spacing and distance.

Fault damage zone deformation bands D2 normal and D3 reverse faults are bordered by deformation bands, forming a fault damage zone. For faults that have associated microstructural analysis, the damage zone width varies from 0.1 to 272 cm. A total of 12 faults with a damage zone width > 10 cm were analysed for spacing statistics (e.g. Fig. 16a). The average Pearson correlation coefficient for each analysed fault ranges from 0.07 to 0.62 with a combined average of 0.4 (see Sect. S9, Fig. S5). A total of 71 % of D2 and 60 % of D3 FDZ spatial distributions have Pearson coefficient distributions with a median <0.5, indicating that there is no correlation between spacing and distance (e.g. Fig. 16c.ii, iv; see Sect. S9, Fig. S5). Analysis of spacing distributions shows that all faults have positively skewed spacing values (see Sect. S9, Fig. S7). These data most closely match the synthetic images in panels (d) and (f) (see Sect. S10, Fig. S10), which is indicative of a damage zone or spatial overprints.

Figure 16(a) Spacing analysis of CSBs hosted in the damage zone of a small reverse fault with up to 20 cm displacement. The image documents the upper end of the fault, approaching the tip. (b) Spacing analysis of dominantly SECBs with rare CSBs not associated with the damage zone of faults. The bands show a near-constant spacing with a median spacing of 1.3 cm. A total of 100 scan lines were taken for panels (a) and (b). The Pearson correlation coefficient values for panel (a) are mostly > 0.5, which is indicative of a positive correlation between the spacing of bands and the distance from the fault plane, as is expected in a damage zone. The Pearson correlation coefficient values for panel (b) are close to zero, which is indicative of an constant spacing. (c) Spacing statistics for selected outcrops to highlight the variation in deformation band distribution across the field site. The figure has been separated into bands that were analysed adjacent to normal faults and reverse faults, where a decay of spacing away from the fault plane is expected, and those that were analysed away from fault planes where no correlation between spacing and distance is expected. Two examples of each have been chosen to represent possible end-member datasets. Panels (i) to (vi) show distributions of Pearson correlation values for each analysed scan line for the outcrops. CSBs are primarily associated with faults and are expected to show a positive correlation (Pearson > 0.5). SECBs, with some conjugate CSB sets, were measured > 2 m from faults and should not show a correlation between spacing and distance resulting in a Pearson value close to zero. Panels (i), (iii), and (v) show examples that match these predictions. Panels (ii), (iv), and (vi) are examples that contradict these predictions. Panels (vii) to (xii) show the spacing frequency distributions for different outcrops. Band spacing associated with faults is expected to show a positive skew. All bands associated with faults show a positive skew. However, variation can be seen with large ranges and a non-smooth curve. Bands not associated with faults are expected to show a Gaussian distribution, representing a regular spacing with noise (Fig. 10b): panel (xi) shows this, whereas panel (xii) is characterised by a positive skew, as would be expected for a fault damage zone. Data for all analysed outcrops can be observed in Sect. S9.

Non-FDZ deformation bands We examined D3 SECBs and CSBs with apparently constant spacing from 28 outcrops where damage zones were not clearly detected; thus, the damage was not associated with a nearby fault. The spacing generally does not correlate with distance from the first deformation band (Fig. 16b, c.v). Many peak Pearson correlation coefficients are close to zero (average of 0.02), with a normal distribution indicating no relationship between spacing and distance (Fig. 16b). However, Pearson values range from −0.65 to 0.61, indicating that there are outcrops that are not associated with a fault that show a distance control on spacing (Fig. 16c.vi; see Supplement Sect. S9, Fig. S6). A total of 10 % of analyses are complex with strongly skewed spacing frequency distributions and Pearson coefficient values indicative of a distance control on spacing (> ) (see Sect. S9, Fig. S8). A total of 43 % of analysed outcrops, however, show variable Pearson values, as the scan lines analyse different parts of the outcrop. Large ranges of values are observed, and, in some cases, these values are negative, which is indicative of an anticorrelation between spacing and distance. This effect can be seen in Fig. S9a where a scan line along the top of the image would result in a negative Pearson value, as observed in the Pearson histogram. This highlights the importance of using multiple scan lines (Sanderson and Peacock, 2019). Data for bands not associated with faults correlate with the synthetic images in panels (b) and (f) (see Sect. S10, Fig. S10), corresponding to constant spacing with “noise” and overprinted distributions respectively. Discrete median spacing values range from 1.3 to 21.8 cm. Equivalent outcrops with D2 bands were not analysed for spacing statistics, as suitable outcrops were proximal to faults and, therefore, did not meet the criteria. Conclusively, spacing statistics have shown that, both close to and far from faults, deformation bands associated with horizontal extension and horizontal contraction are characterised by regular spacing (Fig. 16c.ii, iv, v). Additionally, the statistics show that while regular spacing is predicted far from faults, aperiodic spacing can also be observed (Fig. 16c.vi).

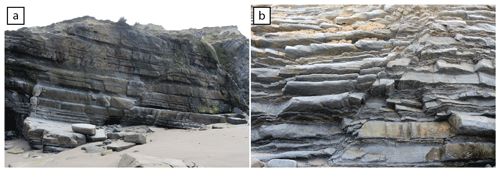

In the following, we will discuss our observations of deformation bands from Castlepoint, New Zealand, and compare them with previous studies to evaluate the control of host-rock properties, tectonic regime, and tectonic setting. The primary results are presented in Table 1. We shall first discuss the association of host-rock properties and tectonic regime with deformation band kinematics and the spatial distribution of bands before concluding with remarks on the implications for fluid flow in this deformed rock package hosted within a subduction wedge.

5.1 Band kinematics, orientation, and microstructure